On the evening of August 19th, 2016, the Milwaukee Brewers rolled into a sweltering Safeco Field for a three-game interleague set with the Seattle Mariners. Also hot that night: rookie center fielder Keon Broxton.

Related Reading:

Can Keon Broxton Make Enough Contact?

Carter-Broxton Plate Discipline

The Mariners, pushing for their first postseason appearance in fifteen years, toppled the Brewers by a final score of 7-6, spoiling Brent Suter’s major league debut. But Keon Broxton knocked the stuffing out of the Mariners’ pitching staff.

He’d been doing this a lot lately, and people were starting to notice. Within a week of this game, Baseball Prospectus, Fangraphs, and Beyond the Box Score all ran pieces extolling his potential. (Fangraphs did so again a week later.) Saddled with an anemic roster after the August 1 trade deadline, the Brewers had precious few reasons to capture the attention of national writers. They had Keon Broxton, though.

After a dreadful first half, during which he hit .125 and struck out in an astonishing 44 percent of his plate appearances, Broxton was coming into his own. Since rejoining the big-league club on July 26, he’d slashed a potent .350/.458/.567. Eight of his twenty-one hits in that time had gone for extra bases. Lest you think his game was one-dimensional, he also stole ten bases in as many attempts. This was the potential that David Stearns and company had seen when they traded away Jason Rogers for Broxton and Trey Supak in a bold offseason move. Hell, this was past that potential. The table, in other words, was perfectly set for Broxton’s finest offensive game of the season.

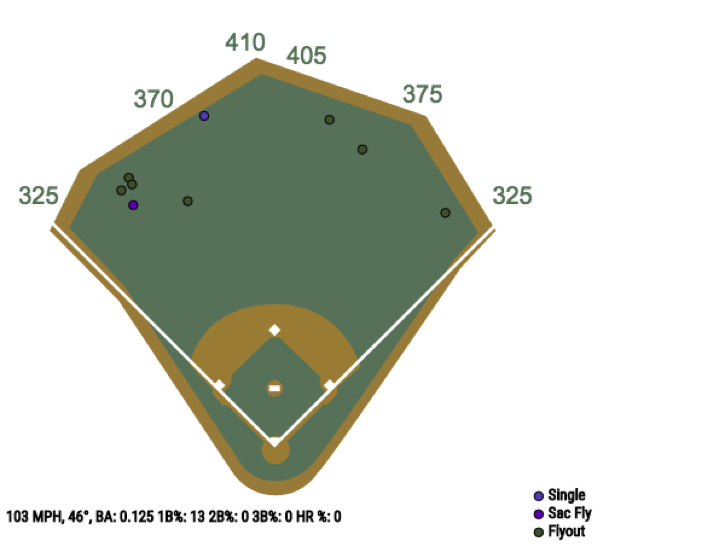

It didn’t seem like anything special at first. Broxton batted second that day, and worked a full count in the top of the first before smoking a sky-high fly ball to left field. The pitch – a juicy Wade LeBlanc cutter – jumped off the bat at 103 miles per hour. But Broxton got under it, lifting the ball into the air at an angle approaching 46 degrees. That’s close to a sure out – since Statcast debuted in 2015, nine balls have been struck with a similar speed and angle, and all but one of them found a fielder’s glove.

The lone exception (in left-center) occurred in April of 2015, when Mike Napoli hit a ball to a tricky part of Fenway Park, flummoxing rookie outfielder Michael Taylor. Napoli, no burner, wound up on first with a single.

So this was a routine out. But Broxton hit the ball hard, and he knew it.

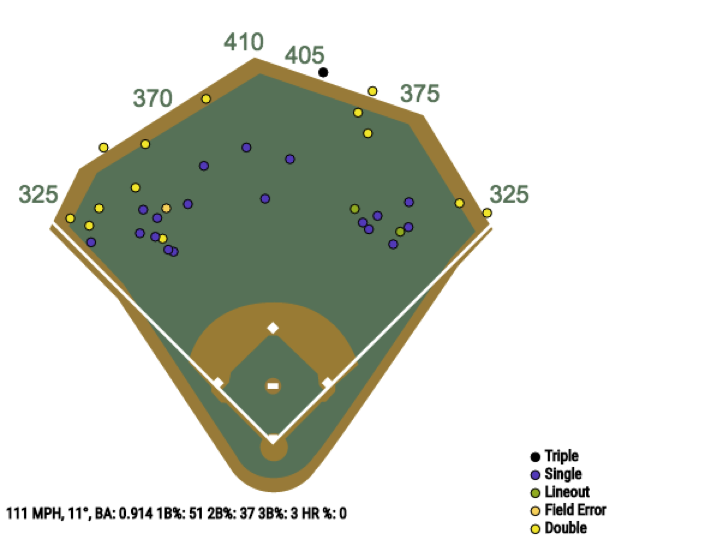

Meanwhile, Wade LeBlanc was cruising. He’d set down the first ten Brewers he faced when Broxton next came to the plate in the top of the fourth. Broxton worked another full count, then unloaded on an 87-mph two-seamer. The ball left the bat at 111 miles per hour, and whistled 274 feet into the outfield on an 11-degree plane. Batted balls with this combination of speed and launch angle fall for hits better than nine times out of ten.

Two innings later, the game became interesting. The Mariners had jumped to a 4-1 lead, but Jonathan Villar led off the top of the sixth with a solo home run. Sensing weakness, Broxton pounced. He watched a first-pitch curveball catch the plate for a called strike one, then crushed another cutter down the left-field line for a solo home run of his own. This time, the exit velocity was 115 mph, with a launch angle of 20 degrees. That spells trouble for opposing pitchers – only two batted balls in the Statcast era have had that profile, and both have left the park.

By the top of the seventh, LeBlanc was done. Broxton wasn’t. He lined an RBI single to the right-center gap, plating Villar and once again bringing the Brewers within a run. This time, his victim was Arquimedes Caminero, whose 98-mph fastball became a 105-mph line drive at an angle of 8.5 degrees.

Broxton came to the plate once more, capping off his day with a walk to load the bases in the ninth. The rally fell short, but not on account of Keon Broxton. His four batted balls for the day each carried exit velocities of over 100 mph.

This virtuosic performance wasn’t exactly out of the blue. Broxton’s average exit velocity for the entirety of 2016 was a scorching 95 miles per hour, putting him ahead of sluggers like Miguel Cabrera or David Ortiz. That’s elite company, and for a time, Keon Broxton played as if he belonged in that company. By the time he went to bed on August 19th, he had raised his batting average to .250, matching his season-high. His 0.283 Win Probability Added (WPA) that game was his best mark of the year. He managed a .294/.399/.538 slash line in the second half of the season before going down with a broken wrist on September 16.

It’s important to note that all four of his bullets on the 19th came against fastballs –had the Mariners fed him a diet of breaking balls and changeups, he may have fared quite differently. Remember, too, that players with Broxton’s swing-and-miss tendencies are inherently risky business. Strong power numbers and a high walk rate help mitigate the risk in his profile, but nothing saps power like a wrist injury. It’s entirely possible that the flame of Keon Broxton burned hot and fast and reached its blazing apex that August night in Seattle. By this time next year, he could be a 27-year-old looking for a minor-league contract, forced out of Milwaukee by some combination of whiffs and Lewis Brinson.

On the other hand – and this is the hand I’m more inclined to believe in the middle of a molasses-slow offseason – he could be Joc Pedersen with better defense and more stolen bases. With six full seasons of contractual control, that would be a uniquely valuable asset for a Milwaukee club facing a long climb to the top of the NL Central.

Great stuff- both on the potential upside and possible pitfalls for Broxton. I’ve been looking for correlations in ball-inplay-stats [BABIP, ISO, LD%, IP%, GB/FB%, HR/FB%, GO/AO%] and swing-stats [Swung at %, Sw. Str.%, SO%, Look. SO%, 1st Str%, BBs] for the top 12 X-vel sluggers in ’16 [left out A Judge]. N Cruz, Stanton, Broxton, Holliday, Cabrera, Ortiz and G Sanchez are the top 7 in order and D Santana is 12th. I think you see the same immense potential in Broxton and Santana if a non-mechanical approach correction is made. Stop taking strike 3. Both players probably look for hard stuff and take curves and changeups consistently. Learn to look for and hit off-speed pitches with 2 strikes.

Thanks for reading and commenting! Your correlations sound fascinating. Anything jumping out to you, aside from the backwards Ks? Seeing Broxton and Santana listed alongside those other names is enough to quicken my pulse.