Upon arriving to the major leagues, Travis Shaw was nicknamed “The Mayor of Ding-Dong City” for his tendency to hit the baseball out of the park. Shaw was drafted by the Boston Red Sox in the 9th round of the 2011 draft and at every stop in the minor leagues he won accolades for his power hitting against right-handed pitching, or his precociously mature approach. This past offseason, the Brewers traded Tyler Thornburg to Boston, relocating the Mayor to Milwaukee. So far, the returns have been outstanding. In seven games, Shaw has eight hits and a .267 average. On it’s own that’s hardly impressive, but seven of those hits have gone for extra bases. And yet, Shaw has only hit one, lone, home run.

This wasn’t supposed to be how Shaw’s Milwaukee career started. Baseballmonster.com keeps track of Park Factors with data going back to the year 2000, and it’s interesting to note that Shaw was going from the third-worst home park for left-handed home-run hitters to the third best. Shaw was predetermined to mash in Milwaukee. Brewers fans, of course, will not complain about the team’s newest acquisition posting a .953 OPS, regardless of the route he took to get there. It appears that Shaw has indeed made some tweaks to his approach that will result in fewer home runs, but a greater result overall.

Better Command of the Strike Zone

As a prep player, Shaw had a higher caliber of training than most. His father was Jeff Shaw, an All-Star relief pitcher whose big league career lasted over a decade. Jeff used his Major League experience and knowledge to pick at the holes in his son’s swing, and the younger Shaw arrived in the pros with an advanced feel for hitting. But his first two years in Boston, Shaw profiled more like an overeager, all-or-nothing hacker. He hit .270 as a rookie with an unimpressive .327 OBP, and last year those numbers cratered to .242 and .306, due in large part to seeing more at-bats against left-handed pitching. Meanwhile, Shaw posted a whiff rate north of 10 percent both years.

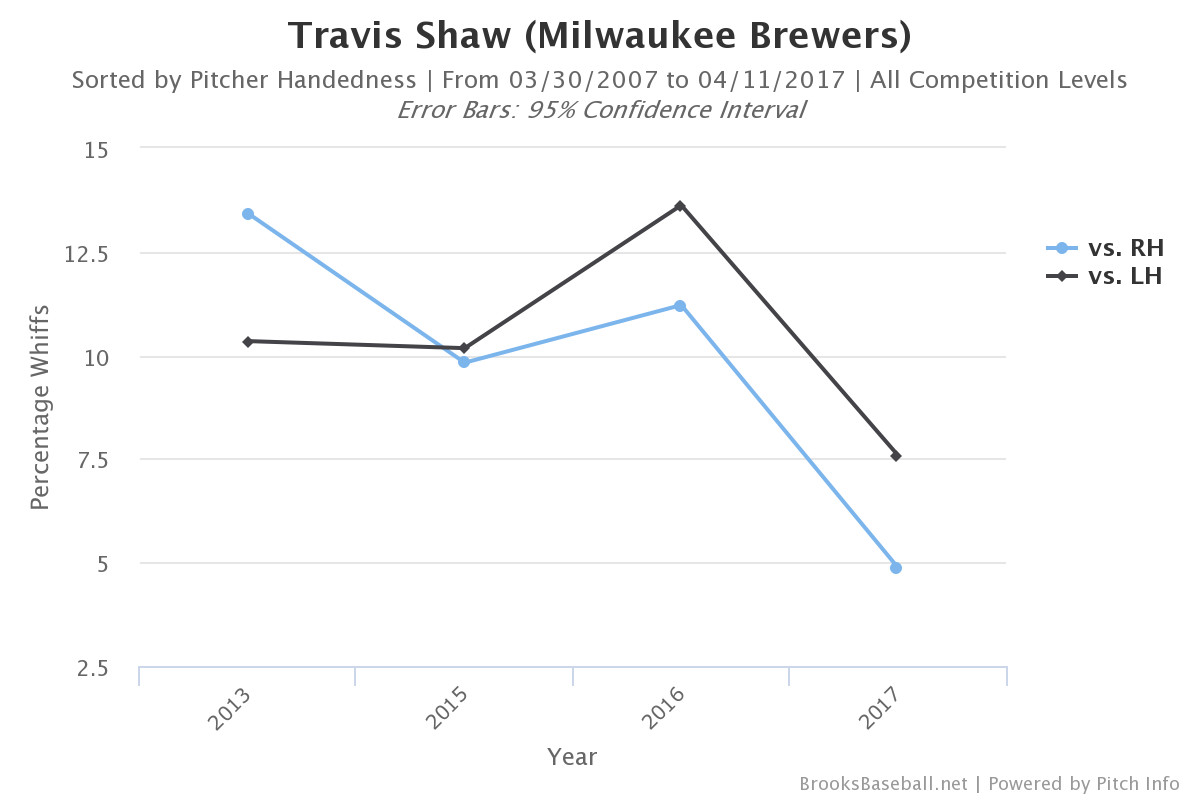

So far, in 2017, that profile has been erased. Shaw’s .268 average through seven games looks awfully similar to that .270 mark as a rookie, but Shaw’s OBP this year is a much-healthier .353. Shaw is seeing a full 0.4 more pitches per at-bat than his career mark so far this season. Furthermore, he’s swinging and missing at a career-low clip:

Shaw was always ahead of the game, thanks to his dad’s teaching, but four years in the minor leagues seemed to screw with his rhythm just a touch. For the first two years of his Major League career, Shaw failed to show that advanced feel for hitting and superior command of the strike zone. Maybe he’s feeling less pressure because he’s playing in a smaller market, or perhaps he’s just grown and matured as a professional hitter. Either way, the end result is that Shaw is controlling his at-bats now, not the pitcher, and that is a very welcome development.

Power Doesn’t Automatically Mean Home Runs

Shaw’s home run output is down, but his slugging percentage is up. Thanks to Statcast, a “power hitter” is a much more nuanced profile than it was a generation ago.

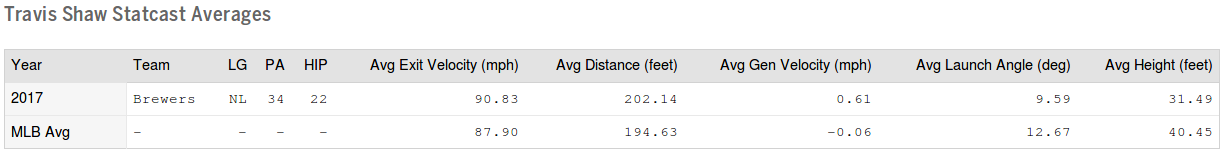

Stacking Shaw’s Statcast averages against the MLB average shows us that he’s hitting the ball harder than average and farther than average. Furthermore, while the average bat is taking a marginal bit of velocity off of the pitch, Shaw is actually adding an average of 0.61 mph to each pitch he sends back out into play:

Furthermore, Shaw’s average launch angle is over three degrees lower than the league average, and those balls are reaching a peak height that is nine feet lower than the league average. Both of these factors make it much more difficult for balls to clear the fence, but hard-hit balls that don’t leave the yard are plenty useful. Shaw’s first week of action in a Brewer uniform has shown us this.

In fact, BP’s True Average metric might be the best reflection of Shaw’s growth as a hitter. He’s put up a .298 TAv so far, which is over 50 points higher from his 2016 mark. Shaw has not been a great defensive third baseman, but his offensive contributions have already overcome that and he’s been worth a fifth of a win alone.

If Shaw can overcome his problems hitting left-handed pitching, he’ll be everything Milwaukee wants in a big-league hitter. And to that regard, the Brewers have faced a pair of lefties so far this young season, and Shaw remained in the lineup on both occasions. On April 4, against Colorado’s Tyler Anderson, Shaw doubled twice in four at-bats. Three days later, facing the Cubs’ Brett Anderson, Shaw collected a single in four trips. Shaw’s platoon splits have leaned to the right in the past, but if he balances that a little bit he’s got the chance to win an everyday starting job.

When the Brewers traded for Shaw this winter, it seemed obvious that the result would be more home runs. The question was how many: Twenty? Twenty-five? Thirty? Today, it seems like those numbers might have been mistaken. However, if Shaw’s new appraoch to hitting means fewer home runs, a higher OPS and, overall, a better hitting approach, the Brewers, their fans, and Shaw will have no reason to gripe.