Jonathan Broxton is terrible. Anyone who’s had the misfortune of seeing him pitch this season can testify to that. In his 33 2/3 innings of work thus far, he’s allowed 24 runs on 40 hits (five of them homers) and nine walks. The resulting 6.42 ERA ranks among the worst among qualified relievers; the same holds true for the 5.49 DRA that backs it up. Broxton’s 2014—in which he posted a 2.30 ERA and 2.58 DRA—looks like ancient history. For this aging right-hander, the road will soon reach its end.

Jonathan Broxton isn’t too bad. Most fans probably wouldn’t pick up on that, but BP doesn’t exactly cater to the masses. He’s struck out 24.1 percent of the batters he’s faced, and walked 6.2 percent—both of which handily beat the major-league averages for relief pitchers. Those marks, together with a solid serving of ground balls, have given him a 2.94 xFIP, 21 percent better than average. Prefer something a bit more advanced? He owns a 2015 cFIP of 90, better than most other bullpen arms. He’s improved notably since last year, when his mediocre 3.96 xFIP and 99 cFIP suggested he might not have much left. At this rate, though, he could go another few strong seasons.

Which version of Broxton is real? Should we (or the fans of a contending, relief-needy team) expect him to play to the level of his ERA and DRA, or to the level of his xFIP and cFIP? There’s a lot to sort through here, so strap in.

By several metrics, Broxton has taken legitimate steps forward since last season. Hitters have swung at 51.5 percent of his pitches, up from 49.1 percent in 2014, and have made contact on 76.3 percent of those swings, a fall from the previous 78.5 percent clip. Those have combined to give him a 12.2 percent swinging-strike rate, which not only tops last year’s 10.6 percent, but also bests his career mark of 12.0 percent, albeit not by much. Plus, although he’s thrown fewer pitches in the zone (46.5 percent) than he did last season (51.6 percent) or for his major-league tenure (52.2 percent), he’s elicited a swing on 35.5 percent of the pitches that miss, much higher than his 2014 rate of 25.2 percent and his overall rate of 29.7 percent. The product of that: He currently sports a 66.4 percent strike rate, an upgrade from 64.4 percent last year and 65.4 percent overall. Thus, he’s certainly earned his aforementioned strikeouts and walks.

But, of course, those don’t comprise the entirety of Broxton’s story. When hitters have put the ball in play against him, they’ve smashed a .365 BABIP, and a warranted one too: He owns a 35.6 percent line-drive rate and (per FanGraphs) a 31.7 percent hard-hit rate. Additionally, the balls they’ve put in the air have traveled rather far—315.6 feet, on average—which accounts for the spike in home runs. In those areas, he’s never done this poorly; nevertheless, we shouldn’t necessarily brush them off as flukes. Something is amiss here.

Let’s look at his arsenal. Broxton uses three main pitches: a four-seam fastball, a sinker, and a slider. The latter hasn’t slipped at all this year—its current TAv against of .204 syncs up with last year’s .194, and with his career .209 mark. It’s also garnered swings-and-misses (19.0 percent SwStr%) and gone for strikes (62.7 percent Str%) to the same extent that it always has, 2014 included.

The issue, then, lies with his harder offerings. Broxton’s 2015 sinker rate of 18.8 percent eclipses his 8.4 percent all-time mark, and the pitch has done little to justify its place in his arsenal. While its career TAv of .301 suggests that it’s never served him all that well, its present .509 (!) TAv simply won’t stand for a major-league pitch. However, the usual culprits—velocity or movement loss—haven’t played a role:

| Period | Velocity | H-Movement | V-Movement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Career | 94.5 | -7.4 | 6.7 |

| 2015 | 94.8 | -7.3 | 7.6 |

If anything, the sinker has packed on a bit more power. And, perhaps uncoincidentally, it’s caused about the same amount of whiffs (8.7 percent) and strikes (58.2 percent) that it did before this year. So what gives?

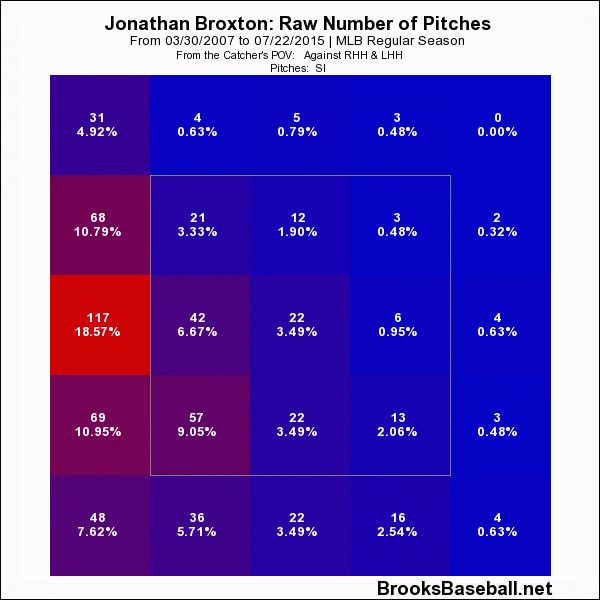

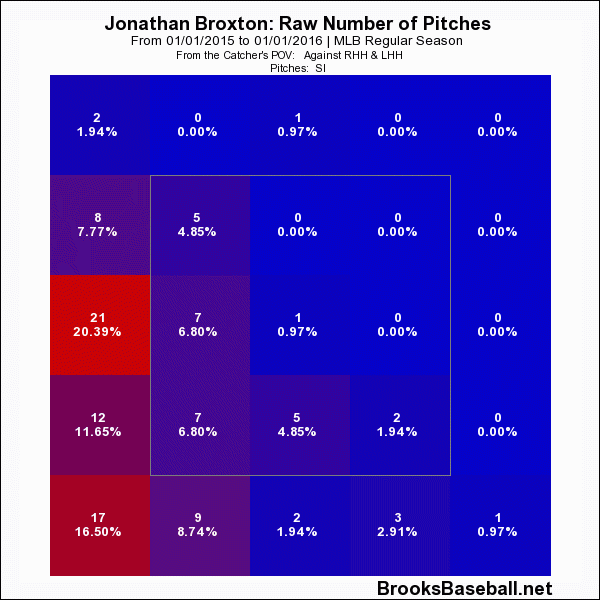

Broxton has always located the sinker off the plate, to the catcher’s left side:

Recently, though, he’s become more predictable in doing that, and in placing it lower in that area of the zone:

Picking up on that tendency, hitters have only swung at the sinkers down and in, and have made better contact (i.e., have had a higher BABIP and ISO) on those swings. Here, the issue doesn’t appear to be stuff, but the usage thereof—which works in Broxton’s favor, since the latter would theoretically represent an easier fix than the former.

The sinker still doesn’t make up most of his pitches, though. That honor falls on the four-seamer’s shoulders, and at one point, it earned it. It’s held hitters to a .239 TAv throughout its existence, riding 96.4 mph of heat and a 9.3-inch drop to greatness. Now that those have fallen to 95.3 and 8.5, respectively, the opposition has upped its game to a .278 TAv. Unlike his secondary pitches, Broxton’s four-seamer simply doesn’t possess the clout of yesterday.

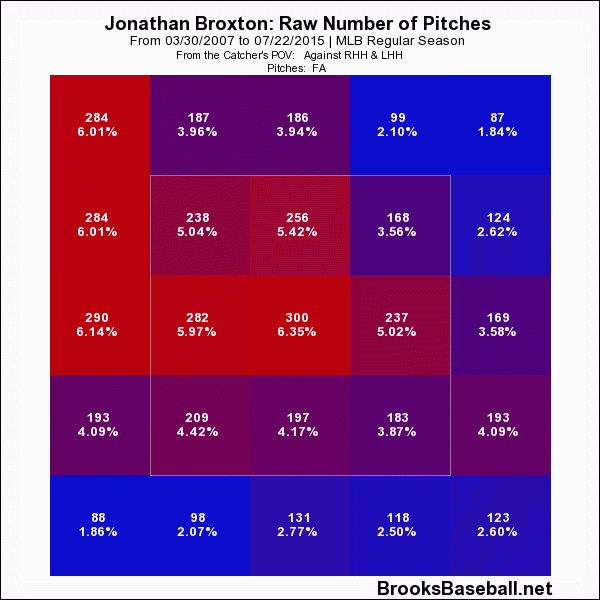

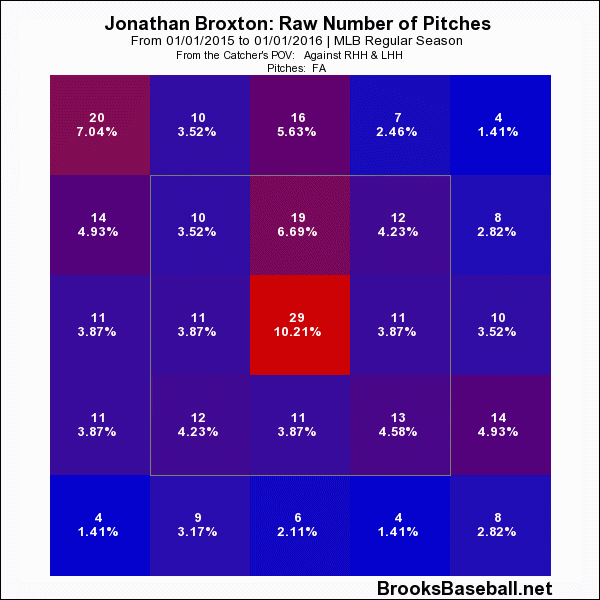

Still, most hitters wouldn’t excel against a pitch that fast—especially one up in the zone, where Broxton’s four-seamer has traditionally resided:

Know what would help them to fight back? The knowledge that the pitcher won’t spread the pitch across the plate; on the contrary, it’ll only come down the middle:

Broxton has kept the fastball high, but it hardly touches the outer reaches of the strike zone. Instead, he’s laid it down the middle—including a stupefying 10.2 percent groove rate—and hitters have pounced. Even with all the heat in the world behind it, a meatball will still come back to bite the man who throws it.

Both the sinker and the slider have fallen from their perches; looking solely at their output would certainly justify any pessimism regarding Broxton’s future. Then again, the stuff remains (for the most part); if Broxton can simply return to the location pattern he once used, the results could come back as well.

There’s one other thing of note here, and it relates to Broxton’s approach. After Broxton allowed the go-ahead home run in a May loss to the Diamondbacks, he and manager Craig Counsell had this to say:

“I’m fine. The ball is coming out fine,” he said. “I’m just getting behind guys I shouldn’t be, especially 1-0 pitches like tonight. It cost me.”

Said Counsell: “It feels like there’s a little bit of a lack of put-away for him. He got behind and you get behind like that, you feel like he should be able to challenge him, get a good fastball and get an out with it.”

Recovering after falling behind has severely plagued Broxton this season. For his career, when he’s gotten a first-pitch strike, batters have a .501 OPS off him; they’ve posted a .517 OPS in such situations during 2015. The problem comes after 1-0 counts: Those have resulted in a .787 OPS against for Broxton all-time, but have led to a staggering 1.212 OPS this year. Together with a 58.1 percent first-pitch strike rate, a slight drop from the 60.0 percent standard he’s established for himself, that has created disaster.

In terms of contextual pitch usage, Broxton has definitely switched something up. Broxton, unsurprisingly, has always used his slider more when ahead in the count:

| Situation | Fourseam% | Sinker% | Slider% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batter Ahead | 69.4% | 10.9% | 15.2% |

| Pitcher Ahead | 60.9% | 4.7% | 29.2% |

| Even | 61.1% | 9.7% | 24.2% |

For whatever reason, he’s now taken that to the extreme, and abandoned the slider when the hitter has the advantage:

| Situation | Fourseam% | Sinker% | Slider% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batter Ahead | 54.6% | 34.8% | 9.2% |

| Pitcher Ahead | 53.7% | 4.9% | 38.9% |

| Even | 49.2% | 18.9% | 27.0% |

Again, his slider rate overall hasn’t budged from prior campaigns—but the scenarios in which he’s implemented them has. Broxton just doesn’t use the slider as a comeback pitch, and its absence has cost him.

Maybe Counsell has told Broxton to feed the hitters fastballs when behind (I don’t base that theory on anything other than Counsell’s quote above, so don’t take it too seriously). The cause for this certainly isn’t obvious, so it might regress away over the second half of the season. Should it remain, Broxton will likely continue to struggle after a first-pitch ball—and, thus, to struggle overall.

Broxton’s right arm has its fair share of mileage on it, and his career doesn’t lack blemishes; despite all that, he only turned 31 in June, so he can presumably play for a few years beyond this one. The Brewers would like to unload his contract onto another club, which would have the option of bringing him back for 2016. In that year, maybe Broxton can rediscover his dominance. While his future is anything but clear, he has more hope for a comeback than you might suspect.

All data as of Wednesday, July 22nd.

Lead photo courtesy of David Kohl-USA TODAY Sports