The Brewers traded away several prolific players a couple months back, none of whom could top Carlos Gomez. His contributions to the Brew Crew will live on in the memories of fans everywhere — unless, of course, those fans see another exciting young outfielder who creates some new memories. Domingo Santana, who the team acquired (along with a heap of other prospects) in exchange for Gomez, has blasted his way to a starting spot on the big-league club, putting up a .291/.388/.558 slash line, .347 TAv, and 1.0 WARP over his 103 Milwaukee plate appearances. With play like that, he’ll continue to see regular time in the outfield next season.

Obviously, random variation will impact a sample size as small as this. Many skills or deficiencies that Santana displays now will evaporate in the future, nothing more than mirages among an expansive career. Nevertheless, his performance to this point does present some intriguing trends — both positive and negative — that could continue into 2016 and beyond.

The Good: His plate discipline breaks down pretty well.

Santana will never run a low strikeout rate. Like many power hitters, he swings for the fences, which means that he’ll go down on strikes in his fair share of at-bats. And, indeed, if he qualified for the batting title, the 31.1 percent clip he’s posted as a Brewer would tie Michael Taylor at the bottom of the National League. If he wants to continue raking, Santana will have to either improve his output here or compensate for it elsewhere.

His peripherals suggest that he can to do both.

The obvious measure of plate discipline, for many fans (myself included), is whether a player can differentiate between balls put outside and inside the strike zone. The hitters who can manage to hold back on the former while offering at the latter will generally excel. Santana has succeeded in both areas for the Brewers:

| Split | O-Swing% | Z-Swing% |

|---|---|---|

| Santana | 24.7% | 68.4% |

| MLB | 30.8% | 64.4% |

Among qualified NL hitters, only Andrew McCutchen (22.9 percent and 68.7 percent, respectively) and Justin Upton (24.0 percent and 67.6 percent, respectively) have O-Swing rates below 25 percent and Z-Swing rates above 67 percent. Sustaining this pace over a full season would thus put Santana in some pretty select company. Not only would it help keep his walk rate up — he’s thus far earned a free pass in 10.7 percent of his trips to the dish — but it could also help him reduce his strikeouts, since he’d take fewer called strikes.

The encouraging signs don’t stop there. When the man at the plate hits a ball out of the zone, it’ll generally carry less power than a ball in the zone would. As Kevin Ruprecht illustrated at Beyond the Box Score, the BABIP for every area of the strike zone tops the marks of all the sections outside it. In other words, it behooves hitters to make contact on their swings in the strike zone and to avoid doing so (within reason) on their swings outside the strike zone. To something of an extreme extent, Santana has lived up to that decree:

| Split | O-Contact% | Z-Contact% |

|---|---|---|

| Santana | 35.1% | 82.1% |

| MLB | 63.0% | 87.1% |

Chris Mitchell noted back in June that Santana had consistently posted low Z-Contact rates in the minors, which didn’t bode well for his transition to the majors. Santana has seemingly moved beyond that, which helps to account for his .380 BABIP and 35.7 percent hard-hit rate. The fact that he whiffs so much on pitches outside the zone will leave him prone to strikeouts, as we’d expect, but his capacity to avoid missing hittable pitches should allow him to get solid wood.

Plate discipline metrics such as these, while generally pretty reliable, can still vacillate. Santana clearly won’t maintain that kind of BABIP; when it regresses, he may start to press, swinging at more pitches off the plate and making weaker contact as a result. He’s shown thus far, though, that he can keep himself under control — and succeed when he does so.

The Bad: He’s had a sizable platoon split.

Few things can suck the life out of a breakout quicker than an inability to hit both kinds of pitchers. BP’s offseason scouting report stated that Santana “struggle[d] with same-handed pitching” — a development that has carried over into the regular season:

| Split | PA | K% | BB% | ISO | BABIP | AVG | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. L | 34 | 26.5% | 17.6% | .429 | .500 | .393 | .500 | .821 |

| vs. R | 69 | 33.3% | 7.2% | .190 | .324 | .241 | .333 | .431 |

Whereas Santana has blown lefties away, righties have comparatively given him fits. In every regard, he’s fared worse when facing someone who throws from his side. Part of this comes from the different location the pitchers have targeted against him:

Santana has hit the ball to left 52.6 percent of the time against left-handers, as they’ve given him inside pitches that he can yank. The right-handers, on the other hand, have held him down to a 29.7 percent pull rate. Santana (like almost every hitter) sees the best results when he pulls the ball to left field, so this gives righties the advantage they need to take him down.

Platoon splits, of course, take a very long time to stabilize. As Santana racks up the plate appearances, he may become an indiscriminate hitter. Even this year, he’s scraped together an above-average campaign off righties, making solid contact (32.4 percent hard-hit rate) and drawing some bases on balls. Failure to do so — and the scouting reports don’t testify in his favor — would lower his ceiling dramatically.

The Good: He’s held his own against breaking pitches.

Think of the stereotypical lumbering power hitter. He can mash hard pitches, but when the hurler comes at him with something slower, it zaps him of his clout. (After enough hardship, he’ll look to unconventional places for answers.) This looked like it could apply to Santana when he came to the Brewers. Brendan Gawlowski wrote this at the time regarding his pitch recognition:

He can cover the entire plate effectively, but he often expands the zone, chasing breaking balls in the dirt… He doesn’t recognize spin well at all, and often flails at sliders and curves, even if they’re in the zone.

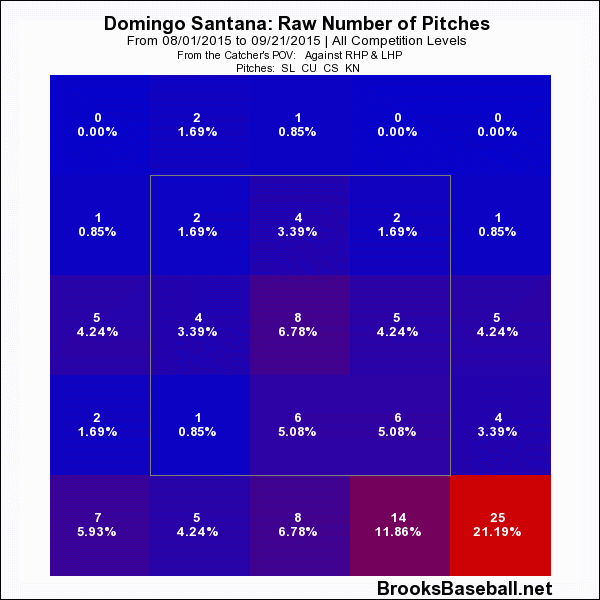

Luckily, Santana hasn’t had to pour out any rum while with Milwaukee. Of the 382 pitches he’s seen with the Brewers, breaking balls (curveballs and sliders) have comprised 30.9 percent. He’s whiffed at 18.2 percent of those — surely a higher mark than he’d like — but otherwise, he’s done just fine. Pitchers have tried to exploit him by burying sliders and in the dirt:

However, Santana has refused to bite, and as a result, a mere 55.9 percent of the breaking balls he’s seen have gone for strikes. His aforementioned knowledge of the strike zone has also come into play here, as he’s taken only 15.3 percent of these for called strikes. In at-bats ending with these kinds of pitches, he’s hit .286/.375/.619, his two long balls and three walks making up for nine strikeouts. Add it all up, and it creates a competent hitter.

The league hasn’t yet had an opportunity to adjust to Santana. Once it does, it may create another hole in his swing, one which would leave him vulnerable to breaking balls. And in all likelihood, he’ll never truly dominate these types of offerings. On the other hand, Santana turned 23 in July, meaning he has plenty of time to fight back against the opposition’s plans. He’ll probably continue to feast on fastballs, which will help cover up anything that ails him elsewhere. Hopefully, his production on breaking balls will include enough of this…

…to negate a healthy amount of this:

The Bad: He’s struggled on defense.

Throughout the minors, Santana has lived and died on his bat. His glove, on the other hand, has typically brought nothing but death. That’s held true for his time in the majors. Across 208.0 innings in Milwaukee’s outfield, he’s cost them one run by FRAA, three by DRS, and five by UZR. Even if he continues to hit like a demigod, he’ll need to accomplish more than this in the field.

FanGraphs’ Inside Edge data reveals the problem — Santana can’t make the big plays:

| Split | 0% (Impossible) | 1-10% (Remote) | 10-40% (Unlikely) | 40-60% (Even) | 60-90% (Likely) | 90-100% (Routine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santana | 0.0% | 4.1% | 30.6% | 45.9% | 81.4% | 99.3% |

| MLB | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

While Santana has yet to flub an easy ball, he has yet to convert a tough one into an out. This fits the bill for a player like him — a lack of range, rather than the absence of smooth hands, has done him in.

Further, the types of chances that Santana’s seen have only exacerbated this:

| Split | # 0% | # 1-10% | # 10-40% | # 40-60% | # 60-90% | # 90-100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santana | 16.2% | 3.6% | 2.0% | 1.7% | 3.3% | 73.1% |

| MLB | 22.2% | 3.7% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 3.7% | 68.5% |

Playing behind a subpar pitching staff, Santana has received a good amount of hard-hit balls, of which he hasn’t taken advantage. We certainly shouldn’t blame him for the failures of his teammates, but he’ll still have to accompany them from here on out. The 2016 and 2017 Brewers will probably keep up this trend of hard contact, and Santana won’t do them any favors by playing like this.

Here, sample size matters the most of all. In the eyes of fielding metrics, 200 innings is nothing. Only after a player has put together three seasons of work can we truly evaluate his talent. Then again, scouting usually tells the truth about a player’s potential, and BP’s offseason scouting report mused that Santana would have to “improve breaks” to become a serviceable defender. Relegation to the bench — or the minors — could await him if he doesn’t.

* * *

FanGraphs’ Kiley McDaniel has said this of Santana:

…[A]fter talking to at least a half dozen scouts about him, I still have no idea what to make of him.

A rebuilding Brewers team will certainly take a chance on an enigma such as him, especially considering the upside he brings. Should Santana solidify his strengths and work on correcting his weaknesses, he won’t make them regret the choice. Like Gomez before him, he may even blossom into a star.

All data as of Monday, September 21st.

Nice piece, Ryan. Dingo is my new favorite Brewer. I think within a few years he can hit 30 HRs and play a competent enough RF to have good value.