Approximately three months into the season it’s become quite clear: the 2016 Brewers are a different animal than last year’s team. For one thing, the second Wild Card spot is a distant–but not unrealistic–dream. The farm system, which lay barren for years, is flourishing with young impact talent. But perhaps the most notable change in the organization has been the management of the starting rotation.

A year ago, Kyle Lohse and Matt Garza were among the worst starting pitchers in all of baseball, yet both remained in the starting rotation well past the All-Star Break. This time around, the team has been far more proactive in removing cancerous growths from the pitching staff. Taylor Jungmann was given just five starts before his ousting from the rotation–as a result, the team has discovered a diamond in the rough in Junior Guerra. Does Guerra get a shot before July for last year’s team? It’s not likely.

About a month after Jungmann was banished to Hell–well, actually, Colorado Springs, not that there’s any practical difference between the two if you pitch for a living–the front office decided to send opening day starter Wily Peralta down the same ignominious path.

For those of us who have watched even a single Peralta start this year, the decision made an awful lot of sense. His only quality start in thirteen tries came on April 24th–against the Phillies, the worst offense in baseball. And even that six-inning, three-earned-run outing barely qualified as a “quality start”–and given the “quality” of the competition, inspired no one. Other than that one outlier he didn’t post a six-inning effort, and he even got hammered by the Phillies in a rematch on June 5th.

The picture gets even uglier when you look at the rest of the starting rotation since Guerra stepped in for Jungmann:

| Name | DRA | WARP |

|---|---|---|

| Junior Guerra | 3.50 | 1.3 |

| Zach Davies | 4.20 | .9 |

| Chase Anderson | 4.25 | .8 |

| Jimmy Nelson | 5.05 | .2 |

| Wily Peralta | 8.03 | -2.2 |

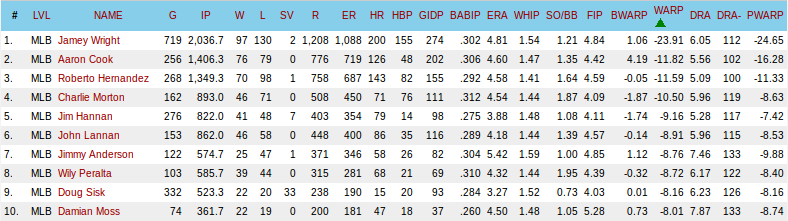

Played out to a full season, it looks like this: Guerra is a three-to-four win pitcher, Anderson and Davies are worth about two apiece, and Nelson’s worth a little less than a win. Then, located in some other dimension, there’s Peralta, who would be on pace to post a Crying Jordan Face in the WAR column if he were still pitching every fifth day. Have you ever wondered what it might look like for a Major League team to take their turns off of a hitting tee? Watching a Wily Peralta start is about as close as you can possibly get, only the tee wouldn’t walk anybody and its 0mph at the point of contact would limit exit velocity. I’m joking here, but it’s because if we don’t laugh at this point we have to cry. In all seriousness: going by WARP, Peralta is the eighth-worst pitcher in MLB history.

Peralta showed promise during his initial call-up in 2012, and he got really lucky in 2014–posting a very good 3.53 ERA in contrast to a very-not-good 5.96 DRA, but his career is now 102 starts deep and he’s cost his team nine wins. That’s not a small sample size–that’s the Peter Principle trying its absolute hardest. Sure, the Brewers had announced their commitment to Peralta in the rotation just a week earlier–but then Matt Garza got healthy. And though Garza was a complete tire fire last year, he looks much better, more locked in, through his first two starts. Garza has a track record of MLB success, interrupted by one stormy blip. Peralta’s track record is, well, that of the eighth-worst pitcher in baseball history.

But with a change in role, Peralta could find success, too. The thing is, that success probably won’t happen in the starting rotation.

Six years ago the Baseball Prospectus Annual featured the then-20-years-old Peralta for the first time, and had this to say:

“A live-armed TJS survivor, Peralta impressed in his full-season debut by striking out more than a man per inning, keeping the ball in the park and getting more than his fair share of ground-ball outs. Peralta’s fastball touches 95 and his slider can be a weapon, but like countless young pitchers before him he’ll need to improve his command and develop a third pitch to be this effective in the bigs.”

Three years later, in 2013, his “heavy sinker” gets its first mention–Peralta indeed made it to the big leagues with three pitches in his arsenal. Since then, he’s added a changeup. These two pitches have combined to do untellable damage to Peralta’s career.

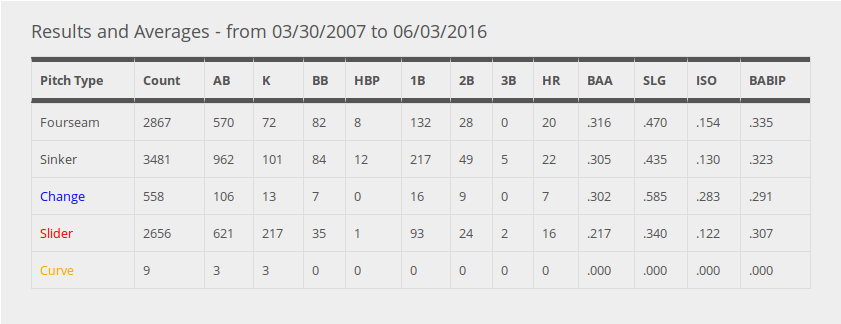

In 106 at-bats off of the change-up, opposing hitters have slugged nine doubles and seven home runs. That’s good for a slugging percentage of .585 and an isolated power mark of .283. Peralta started using the change to combat the fact that he was getting killed by left-handers–instead, lefties have feasted on the changeup, too.

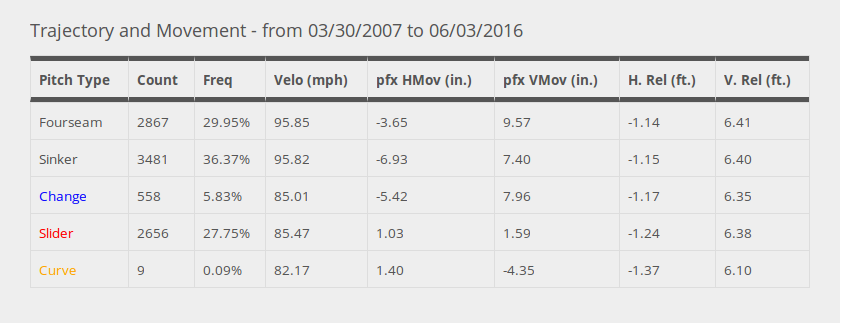

Peralta’s sinker has actually been his most frequently-used offering in the big leagues, but it hasn’t been very good. In theory, he’s doing everything right. His sinker and fastball velocity are practically equal, and the fractional differences in release point are so minuscule as to be indistinguishable to the human eye from 60 feet, 6 inches.

But the sinker is generating a .305 batting average and .130 ISO–on a pitch that, ideally, should get beaten into the ground. His fastball, which looks like his sinker with less exaggerated movement, is also generating similar stats:

Only the slider–Peralta’s best strikeout pitch by a wide margin–is doing its job of getting people out. Peralta is generating an impressive whiff rate of 34 percent when he throws the slider, and he likes to throw it in two-strike counts–it’s his “finishing move,” so to speak. The issue is, hitters will frequently tee off on one of his other offerings well before finishing them off is even an option.

Could Peralta turn things around as a starter? Could a stint in the minor leagues lead to renewed focus, improved secondary offerings, and a new leash on life for the once-promising pitcher? It’s not impossible. Junior Guerra’s career was in a far more desperate state at age 27 and he’s doing alright. But the odds of it happening–with 102 starts of evidence that Peralta’s not a replacement-level starter–are really slim.

Furthermore, the PECOTA player projection system suggests that this might not be an efficient allocation of time and resources for Peralta, or the Brewers.

Peralta’s BP Player Card features an extensive list of historically comparable players–in fact, every single player card does. But we can take a cursory glance at Peralta’s card, and an obvious pattern emerges:

1. Ivan Nova was a decent fifth starter for the Yankees until a partially torn UCL. Since then, he’s been sub-replacement-level on the aggregate. But, as Nicolas Stellini noted for BP Bronx, he was quite effective pitching out of the bullpen earlier this season. Huh, he had a sinker and fastball that butted heads when he started, and when he moved to the bullpen he scrapped one and saw the other become much more effective. How about that.

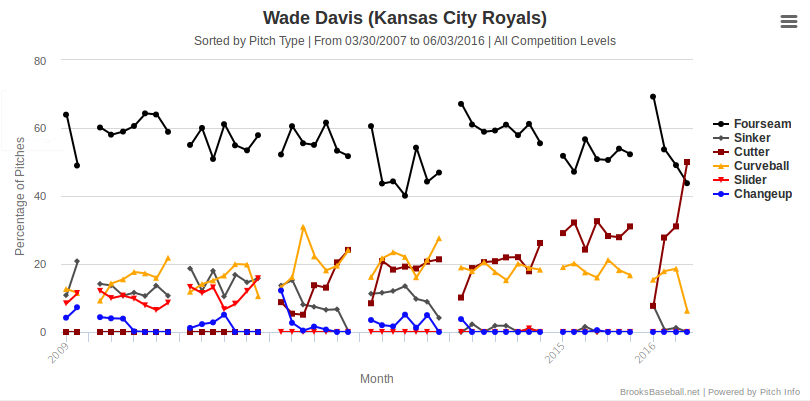

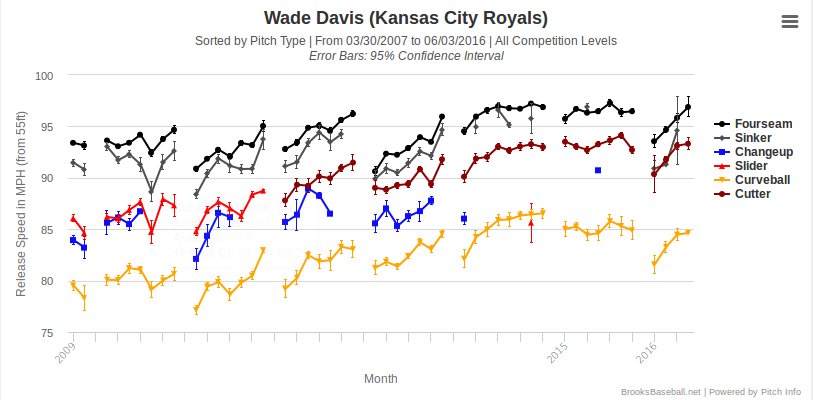

2. Wade Davis is this generation’s poster child for the starter-turned-bullpen-ace, and he did it by simplifying his arsenal. Davis came into the league with five different pitches and not enough command to manage a five-pitch arsenal. As a result, he was plagued by inconsistency during his days as a starter. In becoming an All-Star closer Davis ditched his sinker and changeup, and traded his slider in for the economy model; a cutter that’s actually been more effective and become his go-to pitch this season:

Davis even saw his already-formidable velocity tick up ever so slightly with the role change. It’s not uncommon for this to happen. And if Peralta, whose velocity is already considered a strength on the scouting report, started throwing even harder, he could become the National League Davis–a reliable late-inning stopper for a champion.

3. Clayton Richard was eventually converted to a reliever after two shoulder surgeries, and given his stuff and peripherals the transition would have happened sooner–but pitching in Petco Park with the old dimensions deflated his ERA from 2010-12. For what it’s worth, if Wily Peralta was pitching with those never-to-be-seen-again pitcher-friendly park effects he’d have won fourteen games twice, too, and we wouldn’t be having this discussion yet either.

4. Jason Davis followed a line of many before him, playing out one of baseball’s classic stage dramas. Young pitcher throws hard. Scouts ooh and aah. Oohing and aahing dies down, everybody collectively realizes that the young pitcher couldn’t reliably hit water if he was throwing off the side of a boat. The decision-makers move the young pitcher to the bullpen, where it’s presumed some combination of his settling down and the laxer demands of the role will combine with his impressive stuff to make him worthwhile. But the young pitcher walks so many hitters that it’s a cause for concern in the bullpen, too, so he’s sent to the minor leagues. Sure, he still throws hard, but nobody oohs and aahs anymore because they all know he’s never going to figure out how to aim it–why waste your time being impressed by an illusion? In his final season he posts an ERA north of six in the minor leagues and his career goes down as nothing but a reminder that throwing hard is great–but you still have to hit the strike zone.

In short: Jason Davis’ career is the worst-case scenario for Wily Peralta.

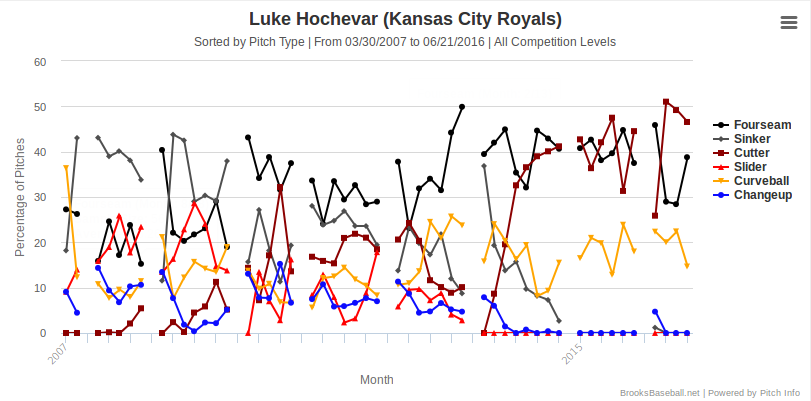

5. Luke Hochevar was the first overall pick in the 2006 draft, and for a while he looked like a textbook example of the Royals’ tendency to screw up their pitching prospects. In a lot of ways he’s a more extreme, more fragile, spare version of Davis. Hochevar used to throw six different pitches with regularity–and like Davis, he found success by streamlining out the unnecessary elements and working with two fastballs and a curve:

If you haven’t noticed the pattern by now, there’s even some Brewer-specific yardage markers on the bottom half of the first page of matches. Manny Parra is sixth on the list and this, alone, should be enough to bar Peralta from ever starting another game in a Brewer uniform again. But you might recall that Parra moved to the bullpen and turned around his garish walk rate–in 2013, the year after the Brewers non-tendered him. And then there’s number nine, Tom Gorzelanny, who the Brewers signed as a lefty reliever–and were forced to use as a swingman due to injuries, even though he was far less effective as a starter–in 2013.

Looking at all the evidence, it is quite clear that Wily Peralta belongs in the bullpen going forward. And if Brewer fans, or Peralta himself, feel any shame or disgrace in that fact they need look no further than Davis and Hochevar, two of Peralta’s most similar contemporaries. Both pitchers were “demoted” to the bullpen because the team’s front office finally admitted that they weren’t good Major League starting pitchers. But this past season, a few years into their respective second acts in the bullpen, each pitcher played a key role on the World Series champion.

Peralta is 27 years old and team-controlled through 2018–it’s not unfeasible to see him in the near future as a power reliever like his two Kansas City doppelgangers, holding down the back end of Milwaukee’s bullpen. He has the stuff to pitch in the major leagues, there is no doubt about that–and in light of the evidence we have, a new role might be exactly what he needs to realize that potential.

Hilariously written. We’d have to double-switch and bring in Maldonado every appearance to have any hope for success. Just don’t trust Wily’s head.