In a year where a stunning amount of Brewers have surpassed anyone’s expectations — Jonathan Villar, Junior Guerra, Zach Davies, Tyler Thornburg, even Hernan Perez to an extent — some of the players the team was counting on have fallen short. Obviously, these players outnumber the surprises; if they didn’t, the Brewers wouldn’t find themselves in fourth place. But of the many who fit this description, I keep coming back to one name: Domingo Santana.

Milwaukee shipped Carlos Gomez and Mike Fiers to Houston last July in exchange for Santana and three prospects. For the 2015 season overall, he held his own at the plate, with a .235/.345/.421 line and a .299 TAv in 145 plate appearances. As a minor leaguer, he’d hit even better — over 426 Triple-A plate appearances that year, he mashed his way to a .333/.426/.573 triple-slash. Since he entered the 2016 season at age 23, it seemed possible, if not probable, that he’d build off his big-league success and become a formidable middle-of-the-order hitter.

And in many ways, Santana has made noticeable progress. He’s reduced both his strike rate (60.4 percent in 2015, 59.5 percent in 2016) and swinging-strike rate (15.0 percent in 2015, 12.6 percent in 2016), according to Baseball Reference. Those decreases have improved his walk rate from 10.7 percent to 12.4 percent, while lowering his strikeout rate from 33.7 percent to 31.7 percent. Yet despite these shifts in plate discipline, Santana’s batting line — .261/.358/.447 across 218 trips to the dish — has hung around the same level as last year. Thanks to the changing offensive environment in MLB, that means his TAv has dipped to .292.

Why has Santana stagnated? He’s certainly crushed the ball this year, tallying a hard contact rate of 39.2 percent and a soft contact rate of 11.7 percent. Each of those marks him as one of the better sluggers in baseball. It’s an analogous tale when you go by Statcast data: Out of the 358 hitters with 100 tracked at-bats, only three — Giancarlo Stanton and Nelson Cruz — have a higher average exit than Santana’s 94.9 mph. But something about those balls has prevented them from paying off.

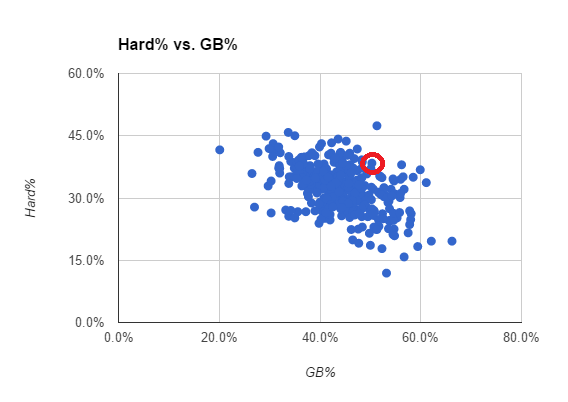

The answer, as is so often the case, lies in the kind of balls that Santana has hit — specifically, ground balls. This year, he’s put the ball on the ground 48.3 percent of the time, compared to a major-league average of 44.8 percent. Not many hitters (among those with 200+ plate appearances) have paired hard contact with that many worm burners:

The red circle indicates Santana’s rough location. He’s not as bad off as, say, Franklin Gutierrez — the one lonely dot near the top of the graph — yet Santana still stands somewhat apart. We see the same problem emerge in the Statcast data as well; by average launch angle, Santana plummets to 314th in the rankings. While getting good wood counts for something, it doesn’t help his cause if those balls don’t go in the air.

Santana has run a pretty high BABIP this year, at .354; you might suspect that his high ground ball rate feeds into that. But Santana’s grounders have been shockingly ineffective this year — he has one of the lowest ground-ball batting averages in baseball. Santana is no burner; he can’t leg out infield hits like Broxton can. Line drives and fly balls have treated him much better, but since he hasn’t maximized his output of those, his production has suffered.

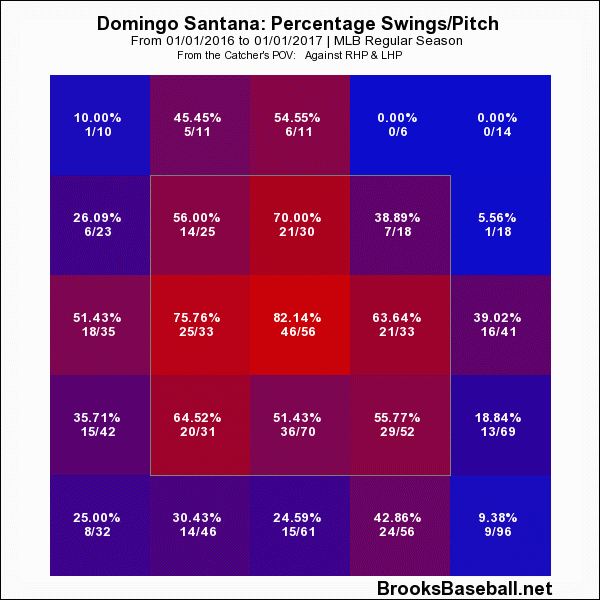

So how does Santana break out of this mold? Most of his ground balls have come on pitches low in the strike zone, as you’d expect; perhaps he should offer less frequently at those pitches. But it’s not as though he hacks away at everything low:

As noted above, Santana has made strides with his plate discipline this year. The problem seems to be baked into his swing. Even when Santana hits a long ball — as he did last week off the Cardinals’ Jaime Garcia — he doesn’t get that deep under the ball, instead going with a flatter swing:

I’m certainly no swing analyst, so I won’t pass too much judgment on Santana. Further, the people who are swing analysts — such as BP’s Brendan Gawlowski — have praised Santana for the “loft in his swing,” which granted him a lot of his minor-league power. I just don’t see that here, though, or in other cuts from Santana. Maybe Santana has adjusted his swing to keep up in the majors; whatever the case, he’ll need to get back his fly ball swing to reach his full potential.

Thanks to their September hot streak, the Brewers have an astonishingly decent shot at respectability heading into 2017. While I don’t predict a return to contention for at least another year, I certainly think the Brewers will take a step forward next season. That means some of the players who haven’t lived up to expectations won’t continue to get chances. Santana needs to prove himself — which means he needs to start hitting fly balls and cut down on the grounders — or else he’ll need to take his talents elsewhere.