Nobody ever expects much from pitchers forced to wield a baseball bat. It’s just an accepted part of the National League game that, one to three times, each starting pitcher will either sacrifice his spot in the order to bunt a runner over or, should he come up with the bases empty, flail about for an inevitable strikeout.

Related Reading:

The Piggyback Rotation

Piggyback Cost-Savings

Of course, that’s not always the case. Brewers fans will fondly remember the power-hitting ways of Yovani Gallardo, and current starter Junior Guerra is a onetime catcher who managed a .229 average on 43 at-bats in 2016. But it’s clear to anyone who watches the game for an extended time frame that these guys are the exception, not the rule. Madison Bumgarner is noteworthy precisely because he shatters our expectations with each home run he mashes.

Statistically speaking, the 2016 Brewers rotation was a nightmare in the batter’s box:

| Name | OPS |

|---|---|

| Guerra | .515 |

| Peralta | .356 |

| Anderson | .217 |

| Davies | .205 |

| Nelson | .195 |

| Garza | .136 |

While talks of bringing the designated hitter to the National League have picked up in the past couple of years, it’s not enough for the Milwaukee front office to sit and wait for a favorable rule change. Fortune favors the bold. Through boldness, the Brewers could develop a strategic wrinkle that would be all their own, and would significantly limit the number of plate appearances seen by unqualified pitchers. The fact that Milwaukee is clearly making positional depth a priority could open up a window a few years down the road to try something brand new, something that could revolutionize the way we approach the lineup card.

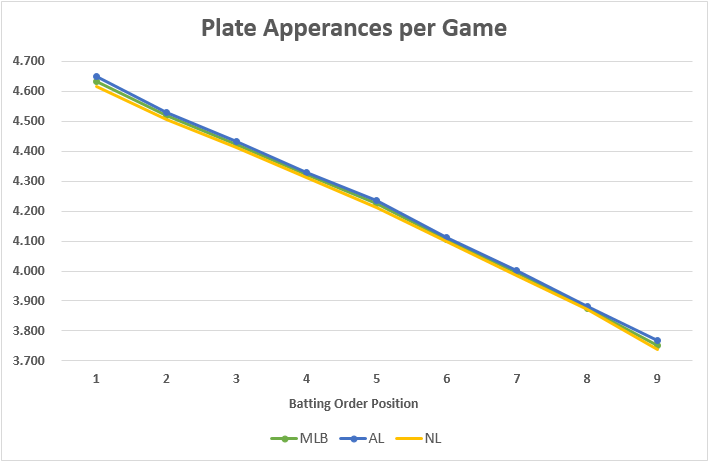

Much research has been done over the years into the sabermetrics of the batting order. How do teams get their best hitters the most, and most valuable, plate appearances possible? Similarly, is there an edge to be gained from hitting the pitcher eighth, or can that be an advantage only with a better-hitting pitcher in the lineup? These are all questions with no definitive answer. That’s not to say that we haven’t given some definitive answers to ageless baseball questions. For example, each spot you move up in the order is worth approximately one-tenth of an additional plate appearance per game as this graph of data from 2014 shows:

This is backed up by Tom Tango’s 2007 publication, The Book, which analyzed historical data up to that year and found that each lineup slot was worth about .11 plate appearances. A few years ago, the Brewers experimented with moving the pitcher up to the eight spot in the order, but that would not be a wise move with the current roster. Giving that six-man black hole another chance at the plate every nine games or so is a terrible, horrible fate that would best be avoided.

Milwaukee can take this even further. If the Brewers are going to be doomed to a pitching staff of duffers at the plate, they could actually move the pitcher lower than ninth in the order, at least for road games. That’s because road teams get to take a turn at bat before their pitcher has to do his thing. For a team with weak-hitting pitchers, the club is looking to lift their starter for a pinch hitter at the first available opportunity. What if I told you that, for a team like the Brewers that is built with a deep bench and positional flexibility, that “first available opportunity” came in the top of the first inning?

Recent research suggests there is an advantage to be gained from radical road strategies during the first inning. Milwaukee would accomplish this goal on the road by starting a batting order of nine position players, using one of those bats to serve as pitcher for one batter in the bottom of the first, and then substituting the starting pitcher into the batting spot that ended the top of the first inning.

If there’s an aspect of the game that’s just as gauche and awkward as pitchers forced to hit, it’s position players forced to pitch. And recent years have seen a surge in occurrences of this anomaly–the You Can’t Predict Baseball blog noted it as early back as 2014, and it’s only surged in the two years since then.

Baseball-Reference keeps a historical list of all players who were primarily non-pitchers who pitched in a game. To make the list, a player needs five times as many non-pitching games as games in which they pitched. But in the early days of baseball, the two-way player was fairly common, just like the player-manager. However, the last player to be designated as a “part-time pitcher” was Johnny O’Brien, a reserve infielder for the Pirates in the 50s.

Because of this, I took every player on the list whose career started in 1960 or later to combine together, as that makes as much sense as anything from a “modern era” of specialization; the cusp of the expansion era. Since I wanted to look at just regular position players, I deleted the stats for the two players who could be considered “part-time” pitchers.

I excluded pitchers that also worked as position players, like Jason Lane and Rick Ankiel, and focused on emergency pitchers. The numbers are brutally ugly. Combined, the pitchers on my short list threw a total of 322 and 2/3 innings. That’s not a small sample size; that’s more than a full season from a starter these days. And in those innings, the numbers are as follows: a 7.11 ERA, a 1.93 WHIP, 1.65 home runs per nine innings, 6.19 walks per nine, and just 3.48 strikeouts per nine.

That’s awful; probably worse than you were expecting. But let’s be honest here–is it comparatively any worse than Matt Garza’s .136 OPS?

Many fans are under the mistaken impression that the starting pitcher must, unless injured, complete a full inning of work per the rules. This is not the case. The rulebook stipulates that the starting pitcher “named in the batting order… shall pitch to the first batter… until such batter is put out or reaches first base.” It’s rule 5.10(e)(3.05(a)), for those scoring at home.

Rarely does this rule come into play, but it was an essential part of one of my favorite old-time baseball stories. The 1924 World Series was the first of the live-ball era to reach a winner-take-all rubber game, and Washington Senators player/manager Bucky Harris took advantage of the one-batter rule to checkmate his counterpart, the legendary John McGraw. McGraw’s best hitter that year was Bill Terry, a lefthanded slugger who was actually pretty tame against lefty pitchers but absolutely pummeled righties. So against lefthanded starters, McGraw would sit Terry and save him to use as a pinch hitter against a righty reliever later on in the game.

Harris’s listed starter for Game 7 was an anonymous, journeyman righthander named Curly Ogden, who had only joined the team after Philadelphia waived him early on in the season. Because of this, McGraw penciled Terry into the fifth spot in the order. But Ogden was just a decoy. After he walked the leadoff man, then issued a walk, Harris called time from his spot at second base, sent Ogden to the dugout, and called for the day’s original scheduled starter: lefty George Mogridge.

Terry grounded out weakly in his first appearance against Mogridge, and struck out in his second plate appearance. In the top of the 6th, Terry came up for the third time with runners on first and third and the Giants trailing 1-0. McGraw pinch-hit for his righty-killer, and Harris immediately pulled Mogridge. In the ninth inning, Harris brought in Walter Johnson, his ace, for the big righty’s first career relief appearance. The game went twelve innings, and Terry would have had as good a chance as anyone in the Giants’ lineup of cracking the fireballing Hall of Famer. However, Terry had been pulled from the game, and had to watch helplessly from the bench as Washington won in the bottom of the 12th inning.

That game turns 93 years old today, but since the rule has not been changed since, our variation on that strategy just might work. The problem is, it could only work if trading that pitcher’s plate appearance for a batter faced by a position player made sense.

Could such a bold move make sense, given the propensity for walks and home runs position players seem to show on the mound? I’d argue that it could, if they were actually prepared to pitch. And though the part-time pitcher feels like a silly anachronism, a throwback to the days of spitballs and spike-first slides, it’s got a more recent hold on the game than one might think. In fact, the Padres are experimenting with a two-way player of their own this spring. Catcher Christian Bethancourt mopped up an inning last season and looked damn promising, if woefully unpolished, in doing so. It will be interesting to track how the experiment goes if Bethancourt makes the team.

But Brewer fans might remember another two-way player quite well. Brooks Kieschnick was a two-way star in college, who gave up pitching when the Cubs drafted him. After flaming out as a big-league outfielder, he spent 2002 pitching at AAA, and the Brewers signed him hoping to effectively extend their roster to 26 men by having him do double-duty as a pinch-hitter and reliever. Kieschnick wasn’t great, but he was fun, and he wasn’t bad either–he paired a .970 OPS with a 5.26 ERA in 2003, and a .689 OPS with a 3.77 ERA in ’04. Either of those pairings is surprisingly decent–and if it were fifteen years earlier, Kieschnick might have been the perfect player to run this experiment with.

And as rare as such a skill set is, the Brewers might have a minor leaguer who could serve as a two-way player. The player would be brought up with the expectation that he was going to perform that way, to be an offensive force who is a competent enough pitcher to record an out or two at the start of the game. I’m talking about 2016 second-round pick Lucas Erceg.

Erceg, who has done nothing but impress with his bat since the Brewers drafted him, was actually a two-way player in college. His player profile on the Cal Bears’ website still lists him as a “Pitcher/Utility” for his position, in fact. And at that level, Erceg was a force on the mound. He put up a 1.93 ERA as a freshman, which rose slightly to 2.53 for his sophomore year. Prior to that, playing at Westmont High School, he put up a 0.59 ERA and 106 strikeouts vs. just 19 walks in 83 and 2/3 innings.

Erceg could not sustain that level of success at the big league level. But I don’t think there’s any doubt he’d be much, much better than the 7.11 ERA-standard for position players pitching. And he doesn’t even have to be much, much better; he just has to be good enough to be less bad than a starting pitcher hitting. Considering the 2016 Brewers employed four different starters who flirted with, or outright succumbed to, the Mendoza Line with their OPS, this is not a difficult proposition.

If you’re worried about using Erceg as a glorified pinch hitter, fear not. The beauty of employing this strategy when you’ve got a deep, versatile roster is that the position player used as the “first-inning pinch hitter” can be just about anyone, provided you can fill out the field behind your actual pitcher when he comes in for someone. Here’s an example, if one were to assume Erceg could play as a two-way player today:

This would be made possible thanks to a batting order full of flexible players.

Villar 2B

Broxton CF

Perez 3B

Braun LF

Santana RF

Shaw/Thames 1B

Two-Way Player P

Arcia SS

Bandy/Susac C

- If Milwaukee hits all the way to Arcia: Villar plays short, Perez plays second, Erceg plays third.

- If Milwaukee hits hit to Erceg: well, that’s pretty self-explanatory now isn’t it?

- If Milwaukee hits hit all the way to Shaw/Thames: Perez plays first, Erceg plays third. Or, flip the two.

- If Milwaukee hits hit to Santana: Perez to right, Erceg to third. Or first, with Shaw to third, if you’re feeling fancy.

- If Milwaukee hits to Braun: Perez to right, Santana to left, and follow the above the rest of the way.

- If Milwaukee goes 1-2-3, Erceg plays third for Perez, who comes out for the pitcher.

- If the catcher makes the last out, just hit through the order. Follow the same strategy as Arcia, and don’t sweat an extra tenth of a plate appearance when you just staked your starter to a multi-run lead.

- Similarly, I’m not going to go into a plan for Villar and Broxton because, again, if they’re making the last out the Brewers are doing something so right that strategic minutiae aren’t going to make a big difference.

As this strategy is such a jarring break from conventional strategy, Erceg’s developmental path is a blessing in disguise, too. The Brewers could convert him to this role now, and begin this experiment in the minor leagues this season. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. But if those teams outperform expectations, well, we might be onto something.

One final thought to bring this series all together: the true strategic value in the first-inning pinch hitter strategy and the eight-man piggyback starting rotation is in using them simultaneously, giving yourself the ability to destroy platoon advantages in all of your road games.

The eight-man piggyback rotation is structured in a rotation of four spots, with those spots held down by “piggyback teams” of two starting pitchers. The ideal setup for this is two pitchers who throw with the opposite hand and have contrasting pitch arsenals and styles.

Now, imagine “starting” the festivities with the third baseman working to the first batter, and then bringing in one of the piggyback pitchers. The opponent doesn’t know until the door opens: will it be the hard-throwing lefty, or the junkballing righty?

Almost a century ago, the utilization of a very similar strategy was enough to sink John McGraw, one of the smartest baseball men in the history of the game, and deliver a championship to our nation’s capital. Could a revival of such a strategy give the future Brewers their signature edge, their definitive exploit that takes them to a level beyond the rest of Major League Baseball?