Since joining the Brewers bullpen in early June, rookie Josh Hader has made quite the impression. Over 20 innings in 15 appearances the lefty has accumulated a sterling 0.90 ERA and a 1.05 WHIP, plus 10.8 strikeouts per nine innings. His versatility and recent history as a starter has seen him used in roles from one-batter lefty-lefty cameos to three-inning long-relief masterpieces. Through them all, he has excelled.

But as the calendar turns to August, there are several reasons to believe that this blazing start to Hader’s career is a smokescreen about to evaporate. Hader’s command, which has been a fairly constant concern throughout his rise as a prospect, has been less than acceptable. His 10.8 strikeouts per nine innings are somewhat mitigated by an average of 5.85 walks per nine. That’s simply not sustainable for any pitcher this successful, and Hader’s luck numbers back this up; they’re all strained well past the point of credulity. Hader’s .175 BABIP, 4.5 percent HR/FB rate, and 97.4 percent strand rate are each, on their own, spectacularly unsustainable. Combined together, they form a house of cards. DRA says that Hader is a 5.18 pitcher, and if he’s going to regress to that point after 20 innings of 0.90 ball it’s going to be really ugly.

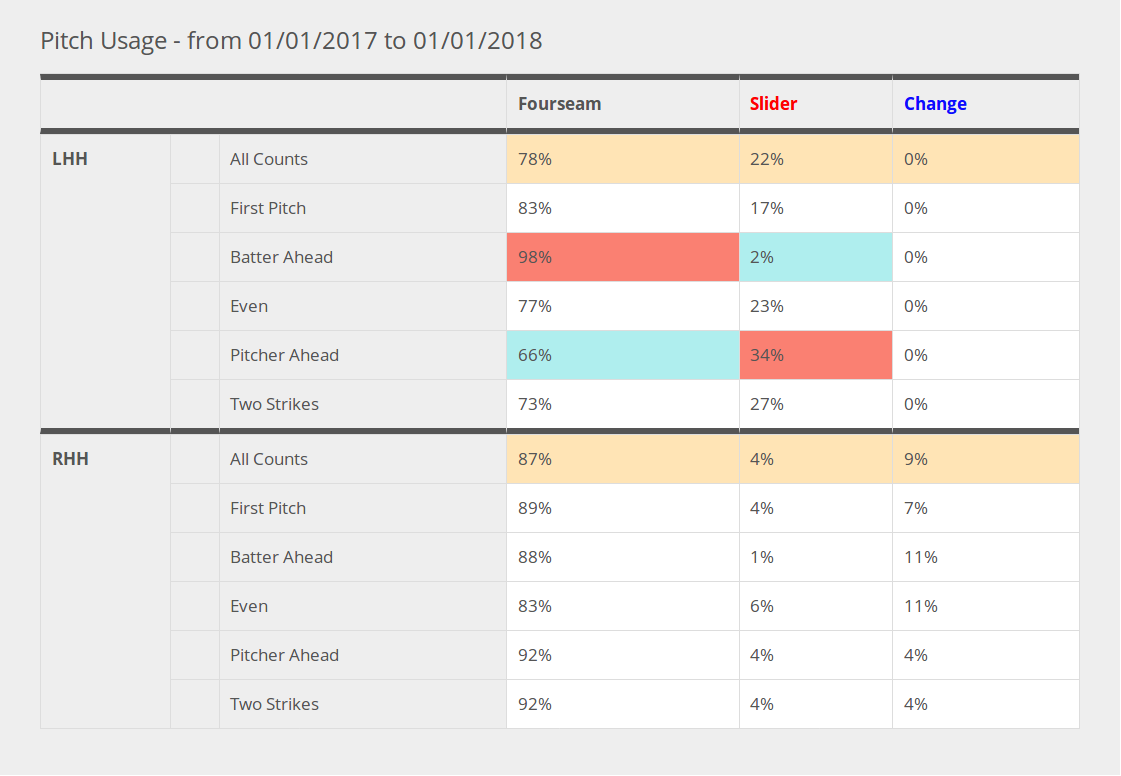

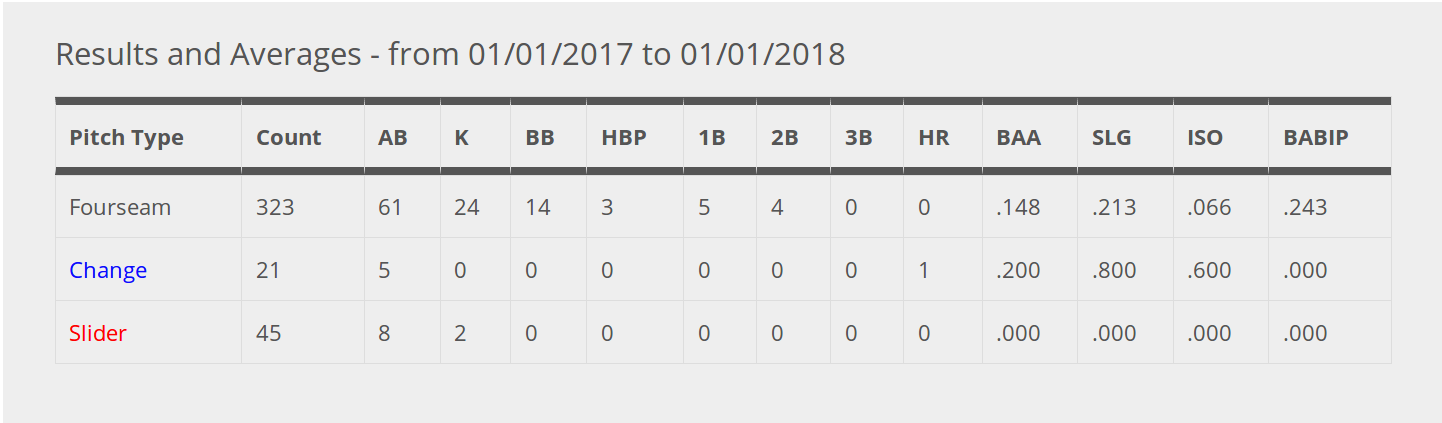

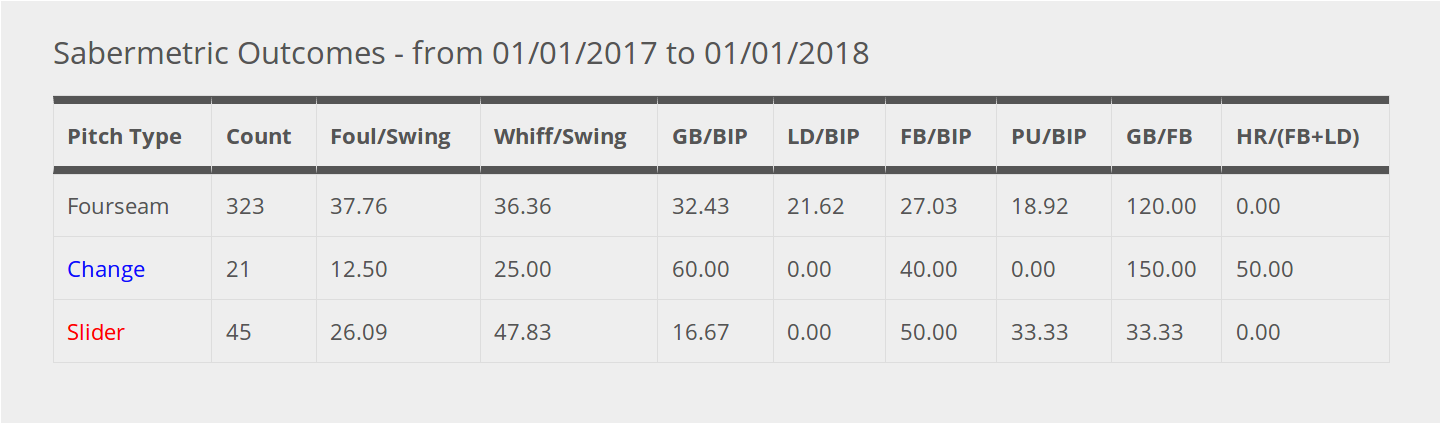

Still, though the extremely short-term future could be less than pleasant, Hader is showing exactly the skills that are supposed to make him a key part of Milwaukee’s competitive near-term future. He’s relied very heavily on his fastball, throwing it over 80 percent of the time (including 87 percent of the time to right-handers). Opponents are hitting .148 against it and whiffing on it at a 36 percent clip. With results like that does it really matter if the hitter knows what’s coming? (Well, provided you don’t miss the strike zone four times in a row. But I digress.)

Hader is 23 years old, and has ample room left to grow and mature as a pitcher. Two big, big questions remain unanswered about who he ultimately will be: can he improve his command to acceptable levels, and can he develop his slider and changeup into serviceable options that he’s confident in using? Using these two questions we can approximate four different career paths for Hader.

Path 1: The Flash in the Pan (command doesn’t develop, secondaries don’t develop)

If Hader remains the thrower he is today, his Major League career will be very short indeed. His fastball has caught the league off-guard, but the league will not fail to adjust in time, and his command problems will make him much more beatable once hitters start turning some of those whiffs into foul balls and prolonging at-bats.

If Hader remains just a chucker, throwing ill-commanded gas with no variety into his prime, his ceiling is as a Quad-A pitcher. This is the type of guy who can look lights-out against weak competition and inspire hope, then dash that hope to smithereens at the most inopportune second. There is still a chance that this could happen, which is why the Brewers were so willingly shopping Hader and his shiny ERA at the trade deadline this year. You don’t have to squint too hard to see a future in which this is the apex of his value.

Applicable PECOTA comparison: Keyvius Sampson was a Top 10 prospect with the Padres. Then, they DFA’d him the following winter and the Reds pounced on him. He made 14 starts and 17 relief appearances from 2015 to 2016, and he cost the Reds 1.2 wins, despite striking out nearly a batter per inning. As it turns out, you need something of a breaking ball to start in this league.

Path 2: The Unpredictable Swingman (command doesn’t develop, secondaries develop)

This is by far the hardest scenario to project for in the bunch. Scouts have said that all three of his pitches have plus potential. If he could develop them into a full arsenal, and develop the confidence to throw any of those pitches in any count, he would be one of the most special pitchers in the game.

It’s easy to say that developing these secondary offerings would be enough to move Hader into a starting role, but his command might be too precarious to support that without improvement. Even Nolan Ryan walked just 4.67 batters per nine over the course of his career. It’s hard to imagine Hader having any sort of sustained success without finding his command first. He could, perhaps, become a contributing high-leverage bullpen arm, but the type who you can never relax around, lest it be one of “those” outings and you need to hook him quick.

Still, a three-pitch mix as good as Hader’s could be will keep teams holding out hope long enough for him to put together a career, and, inevitably, it will be an interesting one. But unless he gets the walks under control it’s going to be one of those careers we remember as “snakebit,” one of those players who always should’ve been better than they actually were. Or he could be one of those guys who doesn’t exactly last in the league but etches his name in history with a stylish six-walk, one-hit-batsman no-hitter that nobody can ever forget.

Applicable PECOTA Comparison: Matt Magill was the Dodgers’ #6 prospect in 2013, just one spot below Joc Pederson. The first knock on him in the “weaknesses” section of that year’s write-up is that his “overall command is fringe,” and that turned out to be just as prophetic as “shows baseball skills” for number three prospect Corey Seager. Magill started six Major League games that year, and pitched in relief five times in 2016. He’s issued 33 walks in 32 innings. In 2017 he finally figured out how to find the plate, dropping his BB/9 to 3.9, but doing so took a chunk out of his strikeout rate.

Path 3: The Power Reliever (command develops, secondaries don’t develop)

If Hader learns to command his pitches, he will succeed at the Major League level. The question is, can that happen? His unorthodox delivery makes finding a consistent release point nigh impossible, and makes correcting the problem much harder from a mechanical standpoint. Brooks Baseball tracks release point data, and backs this up: the 95 percent confidence interval range on Hader’s horizontal and vertical release are larger than any other Brewer reliever, even Corey Knebel, the second-wildest arm in the bullpen.

(Note: don’t be fooled by the size of the graphs. Look at the scale, and look at the confidence interval numbers. The visuals are misleading.)

Hader’s optimized comparison has always been Chris Sale, whose delivery and release point suffered the same nitpicking once upon a time. Sale has walked less than two batters per nine the past three seasons. While he never struggled with command to the extent Hader does, he did not have that kind of pinpoint aim earlier in his career. Even if Hader can cut, let’s say, two and a half walks per nine from his current total he’ll be able to shed the “wild” label and become a very capable out-getter.

But the hard truth of it is, a one-pitch pitcher has no chance of making it in a starting rotation. In fact, even a two-pitch starter is a liability. If you don’t have at least three weapons to choose from, hitters will become familiar with your offerings in a hurry as you pass through the order multiple times. By the third time up they’ve seen literally everything you have to offer, and they’ll be ready for you. Following this path, Hader fails to crack the starting rotation but develops into one of the most electric bullpen arms in the game, with a fastball that takes no prisoners and the ability to take control of every at-bat he’s in the game. We’re playing in an era in which the relief ace has far more value than ever before, so that’s hardly a bad result for Hader or the Brewers.

Applicable PECOTA Comparison: Archie Bradley, who was converted to the bullpen by the Diamondbacks this season and has become an elite high-leverage option for them. Bradley’s got a decent curveball that he still uses, even out of the ‘pen–so this isn’t the most accurate comparison. But even beyond Bradley, the trope of “elite starting pitcher prospect doesn’t develop enough pitches to start and excels in the bullpen” is one that plays itself out every single season. For a local example, just remember Will Smith.

Path 4: The Really Good Starter (command develops, secondaries develop)

Hader doesn’t like to throw his changeup or slider often, but they’re not bad pitches. Hitters are 1-for-5 against his change (with the one hit being the only home run he’s surrendered in the bigs), and 0-for-8 with two strikeouts against his slider. His slider actually generates a whiff rate of nearly 48 percent. But they both come in as balls approximately 50 percent of the time, which makes the hitter’s job much easier.

If Hader can not only get his fastball under command, but take control of his other two pitches as well, then the sky is the limit, just as it has been through his rise up the minor league ladder. If that happens, keeping him in the bullpen would be a waste and a mistake. With his arm capable of pitching deeper into games, three plus offerings, and no significantly threatening control issues in play, Hader is a no-brainer to attempt the rare bullpen-to-rotation transition. He wouldn’t be the first pitcher in history to squeeze out a roster spot from the need for a reliever, only to claim a starting job at the first opportunity; in fact, Chris Sale himself made 79 relief appearances before converting to the rotation.

Hader’s deceptive delivery and big-time velocity make him tough to hit. If he could complement that mid-to-high-90s fastball with an improved slider and changeup, both in the low 80s range, it will add two whole new dimensions to the challenge for hitters and make things even more difficult. If he could further limit the walks he allows he still has the potential to be the best pitcher on the Milwaukee staff.

Applicable PECOTA Comparison: Hader can actually count a sizable number of interesting starters among his PECOTA comparables. There’s Carlos Carrasco, Jake Odorizzi, and Zach Davies on the first page, three high-strikeout-rate guys who might not be aces, but are dependably good mid-rotation guys who can crank it up and compete with almost any pitcher in the game. The second page features Gio Gonzalez, Matt Moore, and David Price, three guys who are having down years in 2017 but have all been marquee starters for most of the decade.

Conclusion

Obviously, there are not just four specific storylines that Josh Hader’s career can follow. Maybe reality will follow a fifth path, and Hader will drop his slow slider in exchange for a hard cutter, attempting to become the left-handed Mariano Rivera with it. Maybe he’ll suffer a traumatic arm injury and come back with “heat” in the low 90s. I sure hope not, but we can never know for certain.

But through 20 innings of a big-league trial, it’s clear that Josh Hader has the stuff to be a superstar. Or a bust. Or any number of things in between.

Photo Credit: Benny Sieu, USAToday Sports Images

I like the article, but I take two issues with ancillary points you’ve made:

1) “the Brewers were so willingly shopping Hader and his shiny ERA at the trade deadline this year” I read no such rumors anywhere on the internets, certainly not MLBTR. While he didn’t appear to be off-limits, I saw no connection of Hader to the Gray sweepstakes.

2) Gio Gonzalez is not having a down year, quite the opposite in fact. FIP might be high, but he’s putting up career-highs in a number of advanced and traditional stats.