Baseball fans have come to expect certain things from Matt Garza: a few gems, a few meltdowns, a lot of intensity, an occasional trip to the DL, and the final stat line of a useful number-three starter. From 2008, when he became a fixture in Tampa Bay’s rotation, through 2014, his first season in Milwaukee, Garza’s ERA+ never fell below 100 and never exceeded 119. Those are the numbers of an above-average major-league pitcher in the midst of a solid career.

Alas, to the chagrin of Milwaukee fans everywhere, the 2015 version of Garza has fallen well short of that standard. Through 16 starts and one extended relief appearance (5 IP), he has managed an ERA+ of only 70 — which means he has been 30 percent worse than league-average. The Brewers seem to hemorrhage runs and hits nearly every time he’s on the mound. A 5.34 DRA (Deserved Run Average) confirms what the eye suggests: for the first time in his career, Garza has been one of the worst starting pitchers in the majors.

The most interesting questions, of course, are why Garza’s performance has declined with such suddenness, and when, or whether, the Brewers and their fans might expect a return to form. The diagnosis seems clear enough, but the remedy might be more elusive.

*****

When he debuted for the Twins in 2006, the highly-touted Garza appeared destined to join ace Johan Santana and fellow-rookie Francisco Liriano atop a dominant Minnesota rotation. Before this great triumvirate could lead the Twins into the World Series, however, Liriano suffered an elbow injury that required Tommy John surgery, and Minnesota dealt Garza to Tampa Bay. In 2008, his first season with the Rays, the 24-year-old Garza played a key role in the miraculous turnaround of that franchise, winning Games 3 and 7 of the AL Championship Series against Boston, and earning the ALCS MVP honor as the Rays made their first and only trip to the World Series. The following year saw Garza amass a 3.16 PWARP, good for 19th among all major-league starting pitchers.

Although he never again reached those heights of postseason dominance, Garza continued to enjoy success following a January 2011 trade to the Cubs (a trade that sent Chris Archer to Tampa Bay). His first season in the Windy City resulted in a 3.32 ERA (3.51 DRA), a 9.0 K/IP, and a 3.94 PWARP, all career-bests. In July 2013, the Cubs dealt free-agent-to-be Garza to Texas for a package of young players that included C.J. Edwards, who is now a top pitching prospect in the Chicago organization. That winter, Garza remained on the market until January, when the Brewers signed him to a four-year, $50 million contract with a fifth-year vesting/team option. Although he managed only a 0.95 PWARP during his first season in Milwaukee, Garza otherwise gave the Brewers more or less what they expected: 27 starts, a 3.64 ERA, and a 1.182 WHIP — which was the second-lowest of his career.

In short, while he never became an ace or even the number-two starter many expected him to be when he broke in with the Twins, Garza from year-to-year has performed like an above-average major-league starter and, with the exception of his brief stint in Texas, has provided value to every team that acquired him, including the Brewers. No one, therefore, could have predicted this train wreck of a 2015 season.

It is easy to identify the primary culprit behind Garza’s inflated numbers: the gopher ball. Through 16 starts, he has allowed 17 home runs, which have resulted in 27 of the 61 earned runs on his ledger. By contrast, in his first 16 starts of 2014, he yielded only 8 home runs for a total of 13 earned runs. This means that had Garza surrendered the same number of home runs so far in 2015 as he did through his first 16 starts of 2014, his ERA — the number by which the general public still measures pitching performance — would stand at 4.27 instead of 5.55.

Why, then, has Garza given up so many homers? A close review of each home run reveals a troubling inability to command his four-seam fastball. Of the 17 pitches opposing hitters have launched over the fences, a dozen have been four-seamers. In some respects this is an old story. Garza relied on his fastball during his meteoric rise through the Twins’ farm system in 2005-06. He still uses it more than any other pitch, and despite diminishing velocity, it remains a quality offering at 92-94 mph, though he has not always commanded it as well as one would like. (Baseball Prospectus‘s Ryan Parker identified this same problem in a fascinating scouting report from late 2013.)

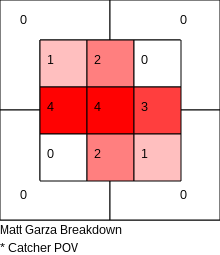

More specifically, in 2015 Garza has struggled to locate his four-seam fastball in Zone 9, which is low-and-away to right-handed batters but low-and-inside to lefties. To illustrate, consider the following zone-by-zone breakdown of all his home runs allowed in 2015. Zone 9 appears near the bottom right and shows that only one of these 17 HR came on a pitched ball that crossed the plate in that precise zone. Reading from left to right, the breakdown further illustrates that in the lower third of the strike zone, Zones 7, 8, and 9, Garza has yielded 0, 2, and 1 home run, respectively:

If Garza has surrendered only one home run in Zone 9, then how could that zone constitute a problem for him? Simply stated, he missed the catcher’s target on each of these homers, and in some cases he missed badly. Of the 17 home runs Garza has allowed, the catcher twelve times had positioned his glove either in Zone 9 or slightly off the plate but still adjacent to Zone 9. The magic of PitchFX technology confirms what video replays show time after time: on each of these pitches intended for Zone 9, the catcher had to move his glove back across the plate and in most cases up in the strike zone in an attempt to catch Garza’s errant pitch. Of those twelve wayward offerings, nine were four-seam fastballs.

Individual at-bats provide compelling examples. Whether attempting to stay away from right-handed batters or bury a pitch down-and-in against lefties, Garza cannot seem to locate in Zone 9. On June 16, with the catcher set up low-and-away, Kansas City’s Lorenzo Cain, a right-handed hitter, blasted a juicy, Zone 5 Garza fastball over the left-field wall. The same thing had happened on April 19 against Pittsburgh’s Pedro Alvarez, a left-handed batter. Again, velocity was not the problem on May 5, when the Dodgers’ Justin Turner drilled a 94-mph Zone 5 fastball over the centerfield fence at Miller Park; the problem was that the catcher had set up low-and-away to the right-handed Turner.

On each of those doomed pitches Garza was behind in the count, but that wasn’t the case on June 16 when he missed up in Zone 6 on an 0-1 pitch to Kansas City’s Mike Moustakas, or on June 27 when a 1-2 fastball caught too much of Zone 8 against Minnesota’s Eduardo Escobar, or again on July 2 when 2-2 offering to Philadelphia’s Cody Asche somehow ended up in Zone 2. Even when he has been knotted or ahead in the count, therefore, Garza has struggled to command his fastball with a Zone 9 target.

Overall, pitches intended for Zone 9 (or just off the plate but adjacent to Zone 9) have accounted for more than 70 percent of the home runs Garza has allowed in 2015, and 75 percent of those pitches have been four-seam fastballs. What, then, is to be done?

Whether the issue is mechanical, psychological, or a combination of the two, I am not qualified to say. It is clear from the numbers, however, that failure to command the four-seam fastball best explains the surge in Garza’s home runs allowed, and the surge in home runs allowed best explains Garza’s inflated ERA.

Besides commanding the pitch better than he has, the seemingly obvious solution might be for Garza to rely less on the four-seamer. One day it might come to this, but for now that solution presents three problems. First, Garza already has reduced his dependence on the pitch. In 2015, he has used the pitch 42.4 percent of the time, compared to 2013 and 2014, when nearly 54 percent of his pitches were four-seamers.

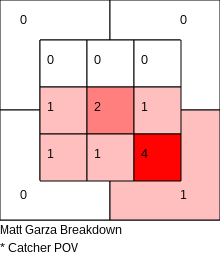

Second, the numbers also show that despite inflated home-run totals Garza has not left a higher percentage of fastballs up in Zones 4-6 than he did in 2014. This season, 114 (17.2 percent) of Garza four-seamers have crossed the plate in those prime hitting zones, whereas last season 230 (17.6 percent) four-seamers found those zones. Those percentages hint at the possibility that Garza’s problem stems from bad luck. On the other hand, the zone-by-zone breakdown of Garza’s 2014 home runs allowed at least suggests that there is more to this problem than luck:

The contrast with 2015 is striking. A year ago, Garza allowed only 12 total home runs (zone breakdown shows 11 because a Todd Frazier homer from September 14 remains undocumented on Baseball Savant). Four of those home runs came on pitches that actually crossed Zone 9. On two of those four homers — May 22 vs. Atlanta’s B.J. Upton and May 27 vs. Baltimore’s Nelson Cruz, both right-handed hitters — Garza hit the catcher’s Zone 9 target. To their credit, Upton and Cruz hit these pitches over the right field fence, but they were good pitches. I hardly need add that they were four-seam fastballs.

To accentuate the contrast with 2015, consider that only three times all season did an opponent’s at-bat result in a home run because Garza missed the catcher’s Zone 9 target with his four-seamer. It is a small sample, but these numbers at least suggest the possibility that Garza in 2015 has more of a Zone 9 problem than a four-seam fastball problem.

The third and final argument against reduced four-seam usage is that Garza likes the pitch, and overall it is still a quality pitch that suits his aggressive approach. Critics might point to Garza’s diminishing whiff rate on the four-seamer, which stands today at an unimpressive 9.82 percent, which is fifth-worst in the majors among starters who have used the pitch 200 times or more. Whiff rate, however, is not always a useful metric for determining a pitch’s overall effectiveness. St. Louis’s Carlos Martinez, for instance, features a similar repertoire to Garza’s and also sports an unimpressive whiff rate (9.95 percent), but Martinez, unlike Garza, is enjoying a fine season (albeit with a 2.70 ERA that masks a 3.81 DRA).

Another possible solution could be to feature more of Garza’s secondary offerings, such as the slider and changeup. Garza has a quality slider that he used at a pretty constant rate (between 21.7 and 25.2 percent of the time) from 2011 to 2014. In 2015, however, he has thrown fewer sliders than at any time since 2010.

In 2011, when Garza surrendered only 14 home runs (compared to 25 in 2009 and 28 in 2010), he also threw his changeup a career-high 343 times, or 10.7 percent of his total pitches. Last season he threw only 24 changeups; so far this season only 37 (2.4 percent).

Most interesting of all, perhaps, is Garza’s two-seam, or sinking, fastball. As we have seen, diminished use of the four-seam fastball in 2015 has not resulted in more sliders or changeups. Instead, Garza now throws his two-seam fastball at a career-high rate of 24 percent, up from 14 percent a year ago. As yet, one can do little more than describe this phenomenon as “interesting” rather than “promising,” for the results of this increase in two-seam fastballs do not quite justify optimism.

When used to best effect, a two-seam fastball should produce a number of groundouts; Pittsburgh’s Charlie Morton, for instance, nicknamed “Ground Chuck,” has used his two-seamer on a whopping 68 percent of pitches this season. With Garza, however, there appears to be no direct correlation from-start-to-start between the volume of two-seamers thrown and the number of groundballs induced. On May 21 against the Braves, for instance, Garza threw only 16 two-seamers but somehow got nine groundballs. Five days later against the Giants, he threw 51 two-seamers but managed only six groundballs.

Nevertheless, if Brewers fans hope to see a rejuvenated Matt Garza giving up fewer home runs and making quality starts as he gets deeper into his 30s, whether or not his four-seam fastball command improves, then his two-seamer will prove useful, if not essential. In fact, one of Milwaukee’s division rivals might provide a good model of an aging-but-effective starter who improved his numbers and prolonged his career by diversifying his pitch selection: A.J. Burnett of the Pirates.

Like Garza, Burnett is an intense competitor who broke into the big leagues with a heavy fastball and high expectations that, despite a few big moments, he never seemed to fulfill. In three years with the Yankees, 2009-11, Burnett gave up a total of 81 home runs. As a 32-year-old in 2009, Burnett threw 48.4 percent four-seam fastballs but “led” the AL in walks. Like Garza, Burnett never was known for his fastball command. With the Pirates in 2015, Burnett seems like a new pitcher. He now uses his two-seamer 51,6 percent of the time and his four-seamer only 12 percent of the time, and he has surrendered only three home runs. Burnett is seven years Garza’s senior, so it is not a perfect comparison. It is evidence, nonetheless, that a pitcher as intense and aggressive as Garza can remake himself if necessary.

Finally, it might be helpful for Garza to feel comfortable. I’m not aware of any particular source of discomfort besides the physical ailment that landed him on the DL earlier this month, but he is only 31, has had a solid career as an above-average starter, and yet he is now pitching for his fifth major-league team, so I cannot imagine that he ever has felt entirely comfortable in one place. Barring unforeseen developments, he will be a Brewer at least through 2017. Perhaps that knowledge, coupled with renewed health, will enable him to relax and discover that, like A.J. Burnett, he has a good deal left in the tank.

Fastball command wouldn’t hurt either.

2 comments on “What’s The Matter With Matt Garza?”