This weekend, I went on Baseball Prospectus’ Effectively Wild podcast and took part in their Brewers preview episode. I came to some pretty pessimistic conclusions about the Brewers future. I don’t see them contending in the next three years, and I don’t see a clear path to that point. It’s obvious what the Brewers need to do — outdraft and outdevelop their opponents and nurture another wave or two of top prospects who can form a long-term core. But when I tried to think of what kind of magic Brewers GM David Stearns could pull to bring the club to contention faster, I drew a complete blank.

This was, I think, the allure of Moneyball for many people. Sociologists like Bronislaw Malinowski found that people tend to believe in magic in situations where there is a marked discrepancy between efforts and results. Moneyball or analytics, or whatever you want to call it, offers the reassuring idea that through some sort of magic — numbers, intelligence, a Process — results can finally be brought in line with efforts and the team will be victorious.

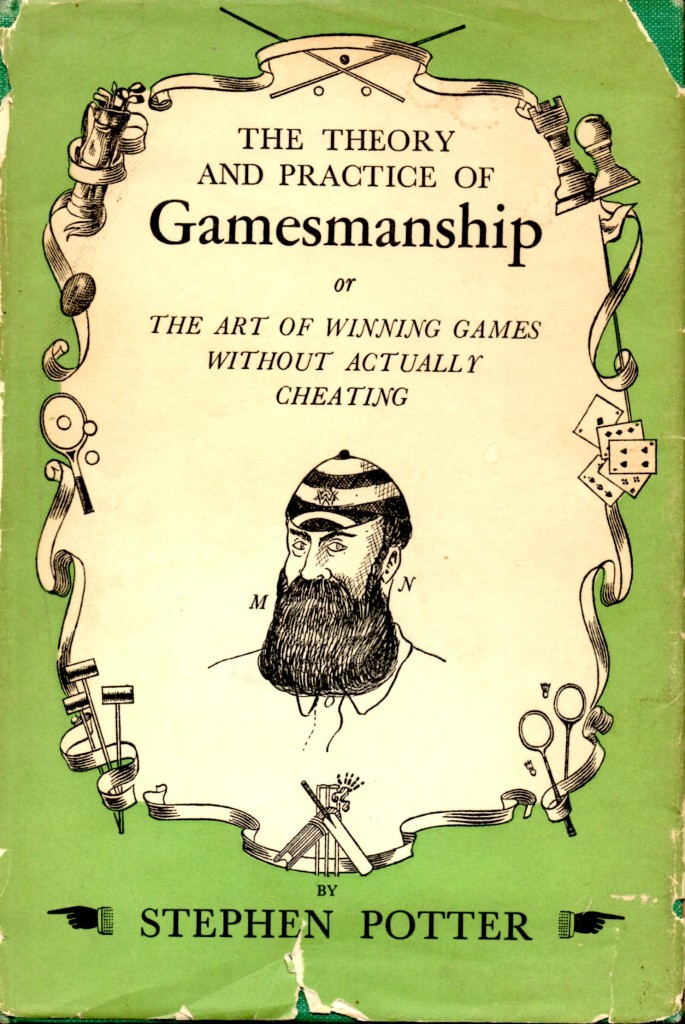

Back when I was in college, I found an old book at a book fair for 50 cents called The Theory And Practice of Gamesmanship, Or The Art of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating. Written by an Englishman named Stephen Potter, it’s a hilarious satire that reveals in all its glory the absurdity of the Victorian ideals of sportsmanship. While it doesn’t sound like it’s related to Moneyball at all, I think Potter’s ideas of gamesmanship have some fascinating similarities to the analytical approach to solving the problem of rebuilding a baseball team.

Chapter III, “The Game Itself,” begins brilliantly: “‘How to win Games Without Actually Being Able to Play Them.’ Reduced to the simplest terms, that is the formula, and the student must not at first try flights too far from this basic thought.” This is the core of gamesmanship. “The assiduous student of gamesmanship has little time for the minutiae of the game itself — little opportunity for learning how to play the shots, for instance,” Potter writes. “His skill in strokemaking may indeed be almost non-existent.”

This is the question I felt like I was trying to answer on the podcast, and the problem it sometimes feels like we’re asking GMs with a Process — whether a stats-type like David Stearns or an old-school scout like Dayton Moore — to actually solve. How can a team win games without actually being good? Now that would truly be magic.

Analytics aren’t going to do that. At one point in baseball’s history, some executives were able to use statistics as a tool to manipulate the predictability of the old guard. Those days are gone. Knowledge of analytics simply isn’t going to allow teams to bridge big gaps in talent, whether acquired through financial resources or assembled through excellent drafting and development.

Gamesmanship works by exploiting the predictability of the opponent’s play style and mindset. That’s the way Billy Beane’s Athletics and other early teams to employ analytics won. But the league adapted quickly, and analytics are no longer magic, they’re simply part of the game. And that’s why I think Stearns and the Brewers — or any other team that sets out on a rebuilding mission — will have to display more than just gamesmanship, more than just an ability to make the right choices and the right calculations.

The real trick for Potter’s gamesman isn’t that he has found a way to magically change the outcome of games. It’s that it never truly matters whether he wins or loses the game itself. “The true gamesman knows that the game is never at an end,” Potter writes. “Game-set-match is not enough. The winner must win the winning. And the good gamesman is never known to lose, even if he has lost.”

I’m excited and hopeful to see what David Stearns and his philosophy can do. But I doubt he will be the one to answer that holy grail of a question to which Potter devoted his book, that question of how to win games without actually being good. Because that’s what I see now when I see somebody peddling a Process. I see somebody selling the idea that no matter what happens, they have still played the game correctly. I see somebody selling the idea that even when they have lost it should not be seen as losing. And that isn’t the work of a magician, just the work of a plain old gamesman.