Every year articles are written about a player’s “peak,” normally trying to identify the best years of a player’s performance, in the abstract, and trying to place some kind of arbitrary boundaries around the data. The problem is that, for the most part, people often use the term “peak” in relative terms. The so-called peak will be dependent on the arbitrary year boundaries one puts around them. Sometimes it will be three years, sometimes four, even five.

The problem with this method is that one can choose any random year and make it say whatever. For example, looking at three-year “peaks” will be different from the data of four-year “peaks” or five-year “peaks” and so on. The problem in identifying which player had the greatest “peak” is identifying what “peak” means or, more helpfully, what it should be telling us.

We don’t often think of a player’s peak as being the greatest single season of all time. It’s a range of years, an average performance within set parameters. But taking a literal definition would suggest that “peak” is the highest or greatest point in a player’s career. Even if a player, let’s call him X, had a better three-year peak (by WARP measures) than player Y, it doesn’t actually mean that player X had a greater peak. If player Y, for example, had a better single-season WARP than any season compared to player X, then technically that player had a greater peak, according to the more literal definition. With that said, it would also mean that player Y didn’t have as long of a peak as player X.

The word peak isn’t typically thought of in terms of height and length, but maybe we should start doing that. Some players may have reached huge heights, even if it was for a brief amount of time, while some achieved a more sustained peak throughout their careers. Both are legitimate uses of the term.

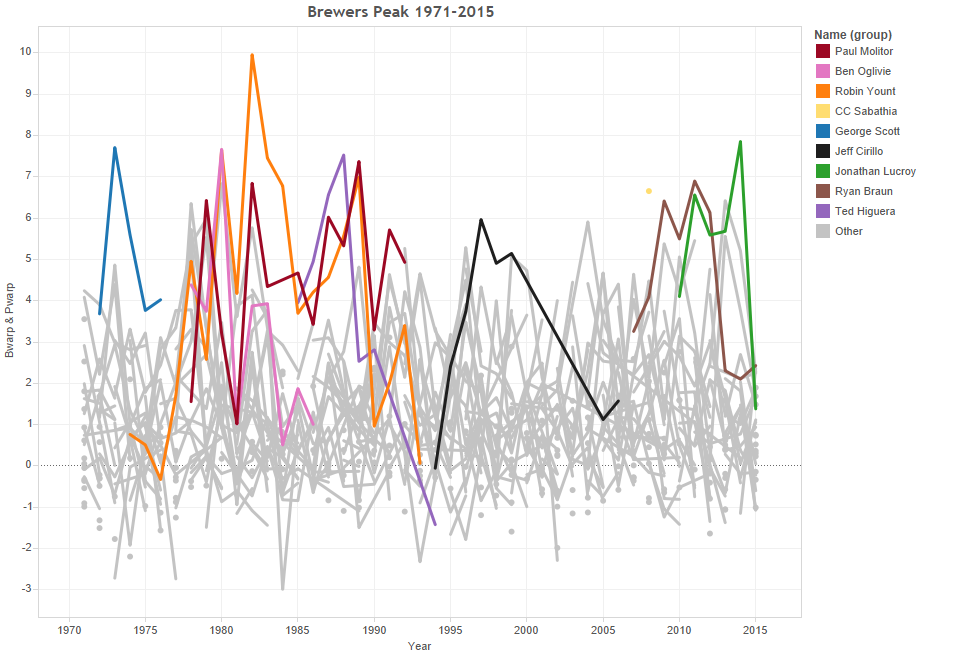

When it comes to the Brewers, though, this type of discussion seems to be superfluous. Looking at the Brewers BWARPs and PWARPs, it’s pretty clear that Robin Yount had the greatest peak in Brewers history, no matter how one cares to define what they mean by peak. (Min 100 PA and min 50 IP, which is why you don’t see Molitor’s 1984 season.)

Even if one chooses to cherry pick the data, it would be very hard to make the case for anybody else.

Paul Molitor, another Brewers great, is a little more of a question mark. Molitor didn’t enjoy the same kind of career that Yount did, at least with the Brewers. He finished with a higher total WARP than Yount, but if one compares the years in which they both played for the Brewers, Yount clearly had the better career with the Brew Crew.

That said, a number of the Brewers’ players reached loftier heights. Molitor’s best season with Milwaukee came in 1989, when he amassed a 7.37 BWARP. That mark, however, was surpassed by Ted Higuera’s 1988 season, Ben Oglivie’s 1980 season, George Scott’s 1973 season, and most recently, Jonathan Lucroy’s 2014 season. Fun fact: Lucroy’s 2014 season was the second best in Brewers history, meaning that only Robin Yount performed better in a single season than Lucroy while in a Brewers uniform.

On the other hand, very few Brewers had more success over a longer period of time than Molitor. From 1985 to 1992, Molitor compiled an average BWARP of 5.09 and never had a season where his BWARP went below three, which for a seven-year stretch is amazing. Unfortunately, during the time Molitor played, we didn’t have the same type of statistical information we have today. With that said, one can look at Molitor’s BB% and K%. They show that Molitor possessed a great eye at the plate. In a number of seasons, Molitor had more walks than strikeouts, which would be a rare feat in today’s game. He coupled that with above-average power, making him arguably the second-best player in Brewers history.

As for Robin Yount, there’s probably little argument to be made about his greatness or even where he ranks in Brewers history. That is to say, it would be hard to argue that he isn’t the greatest player to ever put on a Brewers uniform. His peak can also be discussed outside the realm of the Brewers universe, though.

After making his major-league debut at the tender age of 18, Yount kept improving until he reached his peak in 1982, producing one of the all-time great seasons with a 9.96 BWARP. Yount was an above-average defensive shortstop at the time, but what separated that season from the rest was his ability to hit for power. In 1982, Yount hit 29 bombs and finished with a .247 ISO, which was the best mark of his career. Oh, and I almost forgot, that season Yount was not only a good defensive shortstop who hit for a lot of power, but he also rarely struck out with an 8.9 percent strikeout rate — a combination that would have any talent evaluator from any era salivating.

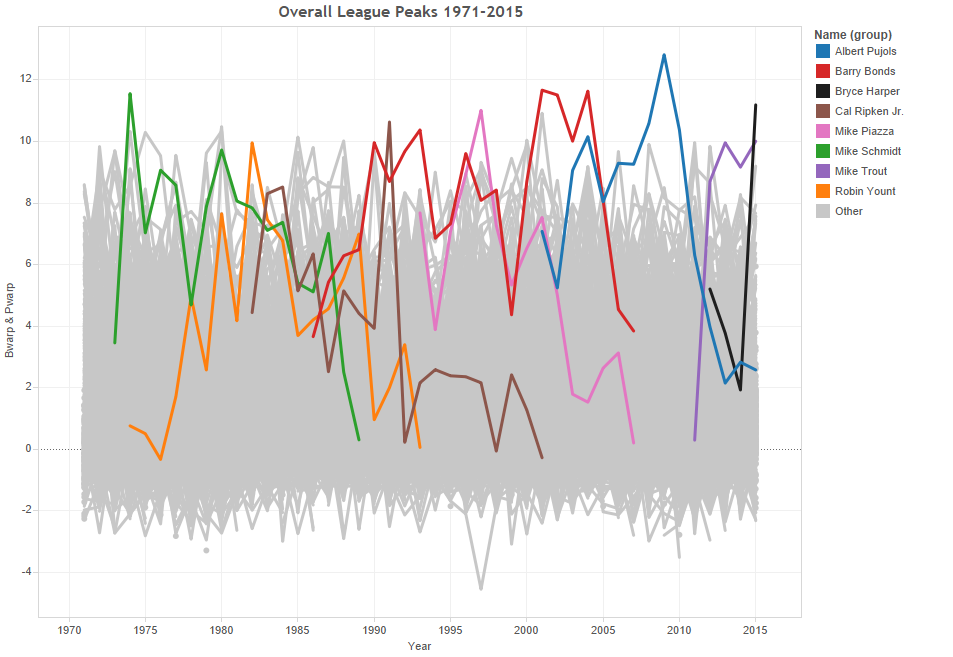

The discussion on what peak means, however, can be had with the Albert Pujols and Barry Bonds cases. While Bonds was a greater player for a longer period of time, he never reached the same heights that Pujols did. Since 1971, Pujols’ 2009 season stands alone. While there’s no argument to be made as to who was the better player, if we ignore PEDs, there’s still a viable discussion as to who had the better so-called peak.

If you are completely turned off by the PEDs, then one can talk about Mike Trout and Bryce Harper. Harper didn’t belong in the same conversation as Trout before last season. Yet, in 2015 Harper produced one of the greatest seasons of all time, even better than Trout’s 2015 season, which BWARP ranks as the best of his career. Conversely, it’s entirely possible, even likely, that Harper will never reach these levels again. Maybe going forward Harper will simply be a six-win player, which is nothing shameful, obviously, that’s a perennial all-star. And let’s say that Trout continues his historic excellence for a few more years. Then Trout’s peak will have been longer than Harper’s peak, but will never have reached Harper’s height.

It’s probably better to talk about peaks in terms of lengths and heights. I think these definitions serve as a better representation of the statements one is trying to communicate, most of the time. Simply suggesting a player had a better peak because he had the better three-year span, alone, is problematic. Therefore, in order to be less arbitrary, it would be better to have a more consistent description of the said peak — such as describing its height and length. This still can leave some arbitrary factor. Maybe, it would be best to simply go with the literal definition, but it’s often less fun and enriching to have those sorts of discussions.