On January 30th, the Milwaukee Brewers made a much-anticipated trade, one that reportedly been percolating since the end of the 2015 season. They traded shortstop Jean Segura and Tyler Wagner to the Arizona Diamondbacks in exchange for Chase Anderson, Isan Diaz, and Aaron Hill.

It’s an interesting trade because, in all probability, the Brewers primarily wanted to acquire two of the three players they received in the trade. They targeted Anderson in the hope that he can become an adequate back-of-the-rotation starter or a usable swingman in the bullpen. It’s hard to think of a 28-year-old pitcher as still having time to tap into his full potential, but as has been discussed here before, Anderson still has an outside chance of doing that. Then there’s Isan Diaz who’s quite an intriguing prospect. Diaz performed poorly in his first season in professional baseball but produced a “herculean” slash line (.360/436/.640) in 2015.

Then there’s Aaron Hill, who the Brewers, more than likely, begrudgingly accepted in the deal. The Diamondbacks sent $6.5 million to Milwaukee in the deal to offset much of Hill’s contract, but ultimately the Brew Crew decided it was best to shell out $5.5 million in order to obtain Diaz and Anderson. One could argue that David Stearns secretly hopes Hill bounces back so he can flip him for a middling prospect this summer; however, this portion of the deal was solely about Arizona’s willingness to part with a high-end prospect in order to offload an unfriendly contract.

With that said, Hill has had a very intriguing career. As a prospect Hill, John Sickels described him as a well-rounded player who could tap into some home run potential while playing solid defense at either second or third base.

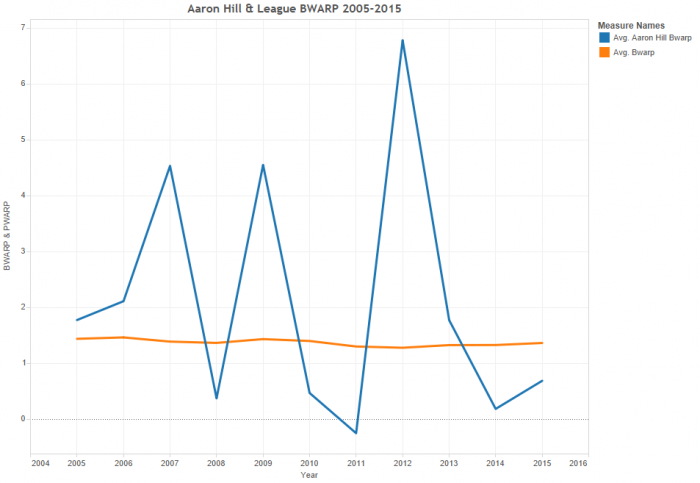

Hill, throughout his career, did all of those things, but at different and inconsistent points. He had two very good seasons and one great season. But what’s interesting about Hill is that those seasons occurred sporadically. In fact, none of those very good performances came in back-to-back years. They were always followed with at least one season of a precipitous decline in performance. In essence, there was a lot of year-to-year variance in Hill’s performance.

From 2005 to 2015 the league standard deviation of BWARP has been 1.91 BWARP (if I include pitchers, so BWARP & PWARP, the standard deviation lessens to 1.74). Hill’s BWARP standard deviation is 2.25. To be clear, standard deviation is a measure of variability, so the lower the number the less variability. The 11-year veteran has been far more volatile than the average big leaguer.

Hill’s best year came in his first full season with Arizona (2012), where he produced 6.8 BWARP. That season, however, followed two very poor seasons including the worst season of his career, in 2011, where he was below replacement level. In that year, Hill didn’t do anything well. He didn’t hit for average, he didn’t get on base, he didn’t hit for power, his defense was subpar, and his base running was average at best. Suuddenly, that all changed. Hill found his hitting stroke again in 2012, slugging .522 – a career high – and producing the best defensive season of his career. He also compiled the best on-base percentage of his career, which culminated in more than a seven BWARP increase from his 2011 season.

From 2005 to 2015, only six players had a bigger increase in year-to-year BWARP, and only one of those players (Aubrey Huff) was below replacement level in the previous season. Interestingly enough, the biggest increase from year-to-year BWARP between that time was Bryce Harper’s 2014 season to 2015 season, which had a 9.3 jump in BWARP.

But the most fascinating aspect of Hill is that after the first three seasons of his career he became a very different hitter. While scouts suggested that Hill had some power potential hidden in his bat, that didn’t come to fruition until his third season in the big leagues, where he hit 17 home runs. It was the first time Hill hit more than ten in a season.

The following season (2008) was mostly a forgotten one for Hill. He dealt with concussion issues all year and only played 55 games. What people don’t talk about, though, is that Hill started doing something very different. For the first three years of his career Hill wasn’t known as a fly-ball hitter, predominantly keeping the baseball on the ground. In 2008, Hill had a ground-ball-to-fly-ball ratio of 0.74. Since that season, Hill has transformed into more of a fly-ball hitter and only had one season since 2008 where he hit more grounders than fly balls.

This change in approach played huge dividends in 2009 when Hill hit a career-high 36 home runs and had an ISO of .213. The approach, however, did cause a slight drop in BABIP, but if you’re hitting 36 bombs, then you can probably cope with the slight BABIP drop. Perhaps the approach went to Hill’s head, however, as he took it to an extreme in 2010, with a 0.65 ground-ball-to-fly-ball ratio. This inevitably played a major factor in Hill’s .196 BABIP, as grounders usually help in having a higher BABIP. This caused Hill to have one of his famous drop-offs in overall performance.

At least Hill’s fly balls still went over the fence in 2010. He finished the season with 26 homers and a 10.8 percent home-run-to-fly-ball ratio. In 2011, Hill tried to rectify his approach at the plate, with a .87 ground-ball-to-fly-ball ratio, but he didn’t hit anything hard and his home run to fly ball ratio plummeted to 4.2 percent. Hill also dealt with a hamstring injury, which admittedly may have played a factor in his poor season and his altered approach.

That next season Hill was traded to the Diamondbacks. The change in scenery and ballpark may have spawned his 2012 season, as it was the best of his career. Hill had a more balanced approach at the plate and had the best defensive season of his career. Since then, Hill’s performance has declined at almost every level. He’s striking out more and walking less. His BABIP keeps dropping even though he’s hitting more grounders than fly balls. In 2015, his BABIP was at .253 and hadn’t been that low since his 2010 season.

Hill will be 34 when the year starts and is probably washed up. While his career has had a ton of variance, it’s unlikely that he’ll produce another great season. Sure, the Brewers can hope that he figure’s things out again, but none of his stats seem to be trending in the right direction. At this point, Hill is probably just a placeholder, clinging on to his last years as a professional baseball player before another young and talented prospect climbs through the ranks.