When Ryan Braun signed his contract extension in April 2011, it was prohibitively large. Braun, after all, had already signed a seven-year contract in 2008, so this deal wasn’t even going to kick in until after the 2015 season. And even though Braun was only entering his age-27 season, he was certainly no sure bet that many years out. The Brewers must have felt that this was their best and only chance to lock up a future Hall of Famer through his prime, but there was certainly a good deal of risk.

According to Spotrac, in 2011, Braun’s $21 million average annual value (AAV) would have been among the ten largest contracts in the game. He was a budding superstar who would go on to win the MVP that same year, but he was certainly being paid like it, and there was little room for any sort of decline if the Brewers were going to avoid being hamstrung at the end of the deal.

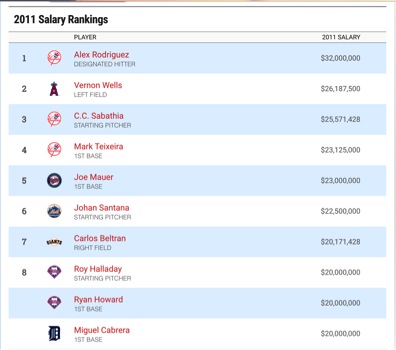

And that list of baseball’s largest salaries in 2011 was full of cautionary tales. Vernon Wells, who was making over $26 million, had posted below-replacement-level seasons in two of the previous three years. Johan Santana, who was making over $22 million, would not pitch at all that season. And Alex Rodriguez was making $32 million, was 35 years old and coming off three consecutive injury-riddled seasons, and was (and still is) under contract through 2017.

One caveat here is that these numbers do refer to a player’s individual season salary, while Braun’s $21 million is the AAV of his extension. I used this $21 million figure rather than any sort of individual season because I am comparing the context of Braun’s full deal with other players’ single-season salaries. In any event, the values will not be hugely different between AAV and single-season salary unless arbitration years are involved, so I believe this use is justified.

Looking at this list, the Brewers had to be confident in at least one of three things: (1) Braun would age better than these other elite players, (2) money would continue to flow into the game and create inflation, or (3) they had no other way of acquiring a superstar through his prime.

Without having any actual knowledge or information from the front office at that time, it’s impossible to know what their exact thought process was. However, I think it is safe to assume that number three was certainly a consideration, and I assume that all front offices think they’re smarter than every other one. But I don’t know what their internal salary projections looked like.

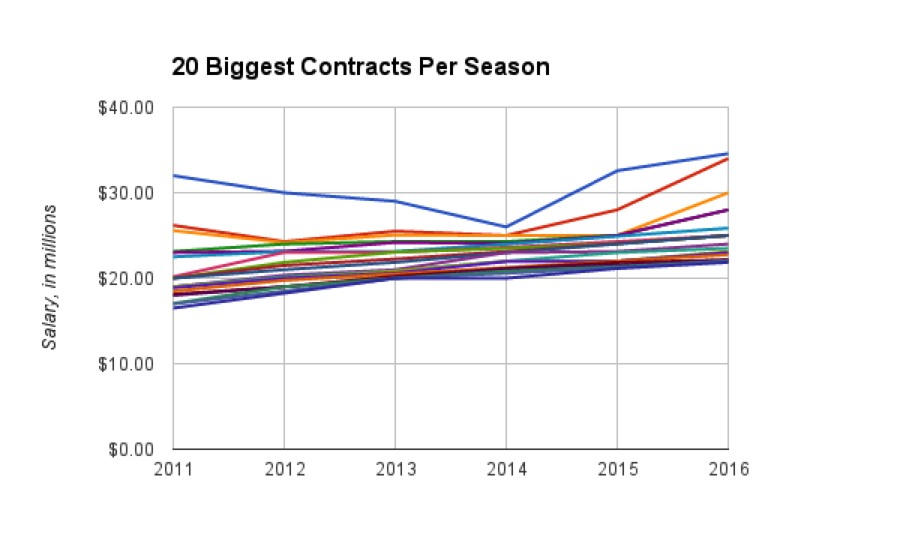

Regardless, though, there would have been some amount of uncertainty built into any inflation calculations. Increasing amounts of money in the sport would increase payroll, but the exact way in which it would manifest itself was unknown. It could have been spent on top-end players and increase the top limit of contracts, or it could have been poured into the “middle class” of baseball players and make mid-tier players overpaid.

As the above graph shows, top-end salaries have in fact risen steadily since 2011 (Alex Rodriguez’s massive deal aside), and they have risen to the point that Braun’s salary is no longer untradeable. When he signed his extension in 2011, he was probably one of the three best players in baseball, and he was being signed to play like it.

But in 2016, he is not one of the three best players in the league; he is probably not even one of the twenty best at this point. But his salary is no longer as exorbitant as it once was. Where his $21 million AAV was in the top ten in 2011, it is no longer even in the top twenty.

It is still a large number, of course, and teams are not going to jump through hoops to pay someone $20 million. But it is no longer such a heavy burden that taking on that type of salary for anyone other than a perennial MVP candidate would be unfathomable.

3 comments on “The Relative Value of Ryan Braun’s Contract”