Is it better to be lucky, or good? History has, time and again, proven this to be a trick question. The truth is, if you want to succeed in anything, you need to be both lucky and good. Building a championship baseball team is no exception. The 1994 Montreal Expos and 2001 Seattle Mariners might be the two most talented ballclubs of my life–but neither one was blessed with the good fortune necessary to hang a banner.

Over the past year, the Milwaukee Brewers’ front office has been plenty good–but they’ve gotten awfully lucky, too.

The quickest way to jump-start a rebuilding process is finding value in players cast off by other teams. In taking something you got, essentially, for free and turning it into something useful. Over the past year, the Brewers have tried to do this repeatedly. Not all of their efforts have worked out–Ramon Flores, Keon Broxton, and Alex Presley have combined for negative one WARP, Will Middlebrooks is whiffing at a 40 percent clip since finally making the big club, and Garin Cecchini hasn’t even looked good by AAA ballplayer standards, and with the artificial stat inflation for hitters inherent in Colorado Springs. But for each of these failures, which cost nothing, the front office has made a number of great calls.

Honorable Mention: Sean Nolin, RP and Rymer Liriano, OF

Once one of Toronto’s top prospects, Nolin is probably best-known as one of the pieces who was sent to Oakland in the ill-fated Josh Donaldson trade. When the A’s traded for Khris Davis this winter, they waived Nolin from their 40-man roster to make room for him–and the Brewers pounced, effectively adding him to the return package.

In Spring Training, Nolin suffered a partially torn UCL, and seemed doomed to Tommy John surgery. But with a partial tear, sometimes the ligament can heal naturally. The Brewers had him reevaluated in May, and decided that things were progressing enough to where surgery wasn’t necessary. If things continue progressing, he could see a couple of September innings. But Nolin’s medical past is far from spotless–a groin injury in 2014 ended his season and caused him to miss part of 2015 as well–and the franchise doesn’t need his immediate contributions, so the prudent course of action might just be to wait for 2017.

Rymer Liriano was struck in the face with a pitch in Spring Training, fracturing several bones, and is expected to miss the entire season. If that hadn’t happened, there’s an outside shot that he’s close to the top of this list thanks to the opportunity created by Domingo Santana’s injury-riddled first half. But on the bright side, he’s working his way back from the traumatic injury.

Update on #Brewers OF Rymer Liriano, hit in face by pitch in spring training: Still working toward getting back on field for baseball work.

— Tom (@Haudricourt) June 25, 2016

For both Nolin and Liriano, the best way to describe this season is “to be continued.” They’ve both got the talent to contribute to the big-league club, and could do so as soon as 2017.

T-5. Jhan Marinez (.4 WARP)

“Jhan Marinez struggled through another Triple-A season plagued by injury, ineffectiveness, gopher balls and the same lack of command that keeps him from leveraging his upper-90s heat and wipeout slider into a major-league bullpen gig; if he ever learns how to pitch, look out.”

That’s the BP Annual, on Marinez, back in 2014. Since then, he has gone unmentioned twice. But a funny thing happened in those two years–Marinez learned how to pitch. During his prospect days, Marinez was known just as much for his live arm–his heat touches 98 on the radar gun–as his complete inability to control it. He regularly posted walk rates north of 6.0, culminating in a 10.3 walks per nine nightmare at AAA Toledo in 2014 that won him a demotion to AA. There, he cut his walks to 4.5 per nine, and that ratio has continued trickling downward ever since.

Still, the Tampa Bay Rays designated the out-of-options Marinez for assignment in May, and the Brewers acquired him for nothing more than cash as a result. And since then, Marinez has been an undeniably effective part of the bullpen. He’s walking just 3.9 batters per inning, striking out 10.08, and posting a 2.60 ERA. All in all, Marinez has been worth four-tenths of a win–and that’s despite the fact that opponents are hitting .380 off of him on balls in play.

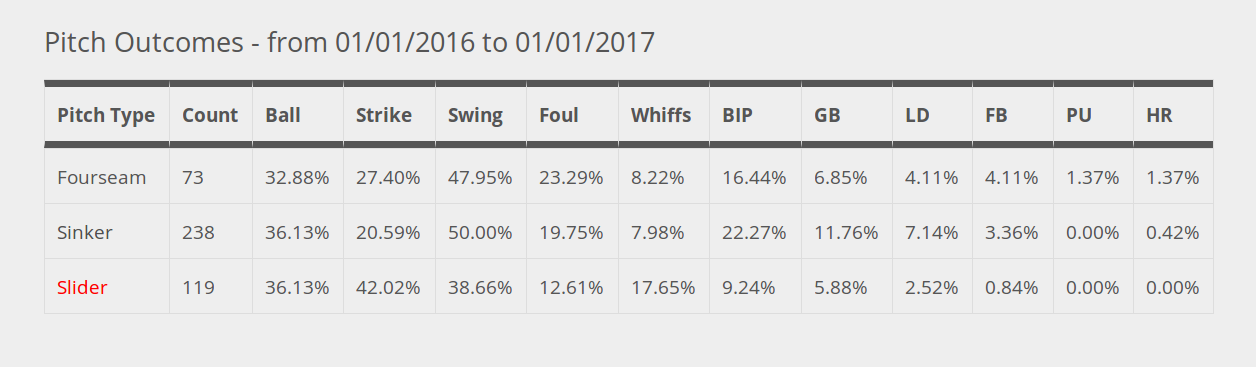

As a prospect, Marinez featured two pitches–a high-octane fastball and an inconsistent slider. Today, both of those pitches are complementary to his sinker, which he throws over half the time:

Clearly, Jhan Marinez learned how to pitch–and the Brewers are the beneficiaries. Marinez also qualifies as a sneaky name to watch for fantasy baseball purposes, too–if Milwaukee goes sell-happy and unloads both Jeremy Jeffress and Will Smith in the next few days, Marinez has classic closer stuff.

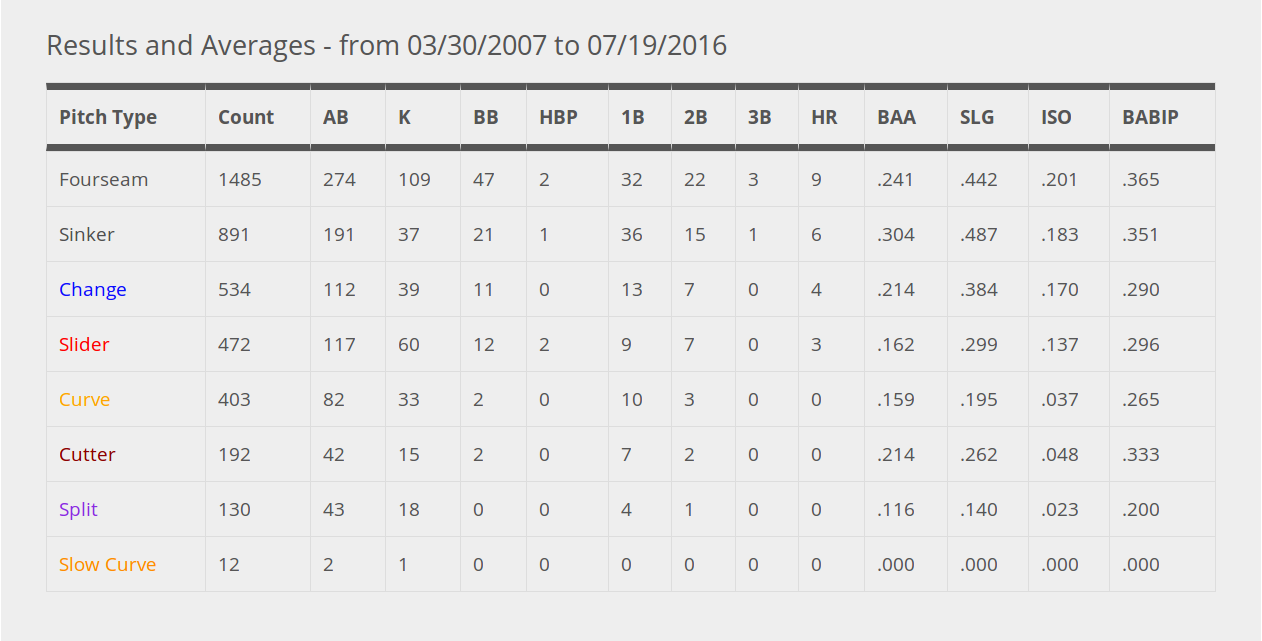

T-5. Carlos Torres (.4 WARP)

The Mets signed Torres to a minor-league contract in 2013, and turned the cutter into his primary pitch. That year, he was worth 1.2 wins. In 2014, that number fell to .5. Last year, he was .2 wins worse than replacement level, as his strikeout and hit rates each hit a career high. The Brewers gambled that last year was a fluke, and that he could be a cheap way to make the bullpen a touch better. They’ve been rewarded with .4 wins, Torres’s highest K-rate in the Majors, and a 2.90 ERA. Jeremy Jeffress and Will Smith get all the press, and Jhan Marinez has the electric stuff, but Torres has evolved into the steady, reliable piece who ensures that the former two can be traded and the bullpen will still be pretty good.

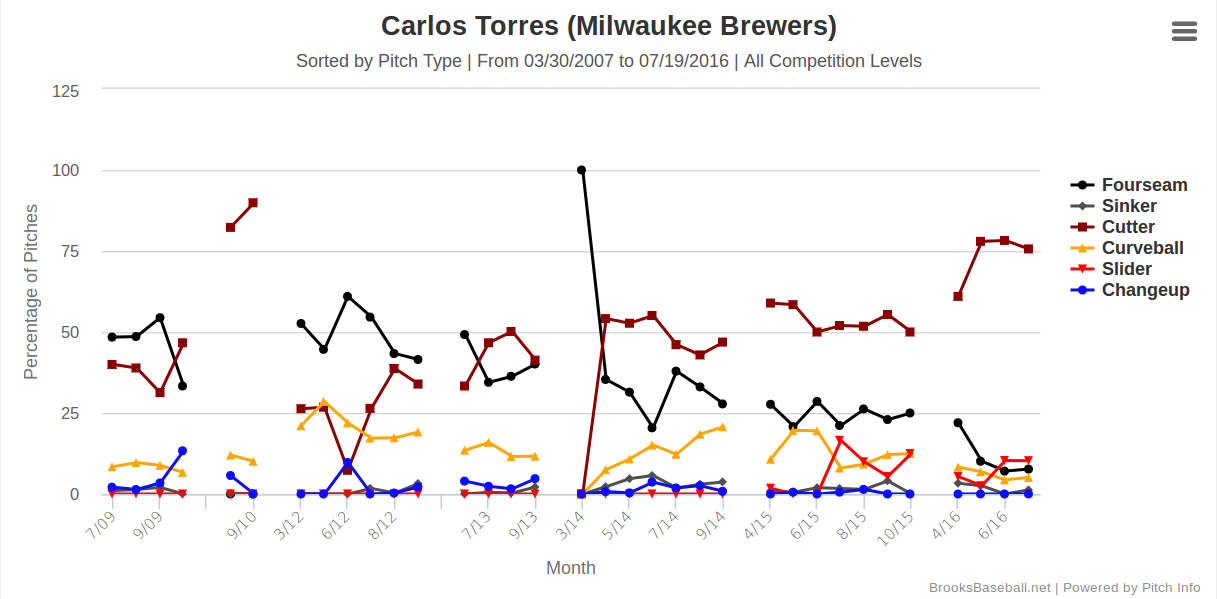

This year, Torres has taken his “cutter as the primary pitch” approach to a whole other level. It’s actually interesting to watch the evolution–as time progresses, Torres goes from throwing the cutter as a second pitch, to a first offering with a plurality in the high-40 percent range, to a first offering used just north of 50 percent of the time. This year, Torres’ arsenal has evolved even further, and he’s thrown the cutter over 75 percent of the time since May:

T-5. Chris Carter (.4 WARP)

On August 7, 2012, I made a simple transaction in one of my dynasty leagues. I don’t even remember who I dropped, to tell you the truth–but I called up Chris Carter from my protected minor leaguers. I tell you this because that was four years ago, and Carter is still on that team’s roster–which is quite remarkable in a high-activity 14-team league. Chris Carter threads the needle of a very specific kind of ballplayer: he’s valuable enough to employ, but not valuable enough to sell.

I can’t pretend that I don’t get it. At times, Carter can be a very, very frustrating player to root for. I’d say the most accurate way to summarize his game would be “extreme risk and reward.” When Carter is locked in, he can carry your team–this April, he put up an OPS of .922 to nicely acclimate himself to his new hometown fans. But when he can’t find his stroke, he turns into a black hole in the middle of your lineup–like this July, when he’s struck out 39 percent of the time and his OPS has cratered to .688. He’s a part-time superstar, but he’s not the type who has outrageous platoon splits so you can’t really tell which Carter is coming to the ballpark on any given night.

At ten million a year, or more, Carter would be a disappointment. But the Brewers are paying him between $2.5 and $3 million this year, depending on performance-based incentives. The value of one Win Above Replacement varies somewhere between $5 million and $8 million, depending on who you ask, and Carter put up .4 WARP in his worst season as a full-time regular, 2015. It was a no-lose proposition, especially since the team had jettisoned both ends of their first-base platoon in the prior month.

Having put up .4 WARP to this point in 2016, Carter has already provided value commensurate with his contract. But it’s worth noting that a year ago, Carter swooned hard in July with a slash line of .109/.176/.304–then neutralized that with a .333/.400/.822 September. More than any player on this list, Carter’s position is far from locked in.

Three years ago, John Sickels of MinorLeagueBall made an absurd prediction that Carter would make an All-Star Team and be an MVP candidate. In fairness, he admitted in the title of the piece that it was an absurd prediction and, like most insane predictions, it didn’t come true. But it speaks to the level of raw talent that Carter has, even if he’s incapable of harnessing it for more than a month or two at a time. In his mid-20s, it was easy to see him putting it all together for a whole year–now, I’d say that’s wishful thinking. But for the cost of less than half a win, he’s been a good value at first base for a team in transition. And if you’re going to take a long-shot gamble on someone, you always want to bet on someone with at least one elite skill.

4. Kirk Nieuwenhuis (.7 WARP)

The Brewers have gotten exactly what they expected from Nieuwenhuis: a smattering of home runs and steals, good plate patience, acceptable defense, and an average that flirts with the Mendoza line. Last year, Nieuwenhuis accumulated .6 wins in 117 plate appearances. This year, he’s been worth .7 in 266. He’s not a black hole, but he’s not all that helpful, either. On the bright side: it’s not like Keon Broxton, Ramon Flores, or Shane Peterson would have done anything more useful. By the time the Brewers are a contender, Brett Phillips will be roaming center field, and Nieuwenhuis will be pinch-hitting and making the occasional spot start, which seems like a good eventual role for him.

For the low-low cost of a waiver claim, the Brewers acquired a player who brings some things to the table, and whose biggest weaknesses can be mitigated in an eventual part-time role. He combines power and speed, and he’s posted better FRAA marks while playing the corner positions than in center–even though he’s capable of playing all three positions. And his struggles to make contact have a pretty easy explanation, too:

The 2015 BP Annual noted that “Nieuwenhuis’ approach is basically to attack any fastball in the zone, take all breaking pitches, and occasionally look stupid on changeups he thought were fastballs.” The pitch-type breakdown of his career supports this. Against overmatched rookies still refining their secondary and tertiary offerings, he can rake–and these are the players he should get his at-bats against in the long run. But pitchers who are pitchers, rather than just throwers, effortlessly turn Nieuwenhuis to pudding.

Still, it remains to be said that a player who can put fastballs over the fence, steal bases, and play three outfield positions is a valuable commodity in the big leagues. Nieuwenhuis might not be too impressive as an everyday centerfielder, but he’s still a worthwhile piece that cost nothing to acquire.

3. Aaron Hill

Aaron Wilkerson and Wendell Rijo are hardly a king’s ransom in prospects, but they’re both intriguing young players–and all the Brewers had to do was take on some salary for about three months to make it happen.

For what it matters, before the Red Sox traded for him, Hill was worth 1.8 wins to the 2016 Brewers. The Brewers’ $6.5 million of his salary is roughly what a single win would be worth in free agency. So for those keeping score at home, the deal was a win on four different fronts–Hill provided value beyond what the team paid him, the team got a better minor-league asset by taking on Hill, he provided value to the rebuilding effort beyond even what the WAR column can quantify, and then Hill was successfully flipped for something that will have value beyond this off-season. Making scrappy moves like that is how you turn a bottom-feeder into a dynasty.

2. Junior Guerra

Look, if you were skeptical of Guerra at first, I don’t blame you. But we’re fifteen games in, and Guerra has been worth 2.1 PWARP thus far. That’s half a season’s worth of starts–if you stretch it out to a full 30, the 4.2 PWARP would have been the 19th-best mark in all of baseball last season. Brewers fans calling him an “ace” might not be all that far off–the 19th-best pitcher in baseball would qualify as a “fringe ace,” the type of guy who could be the #1 on a middle-of-the-pack team, or the #2 on a championship contender, or the #3 on the best pitching staff in the league.

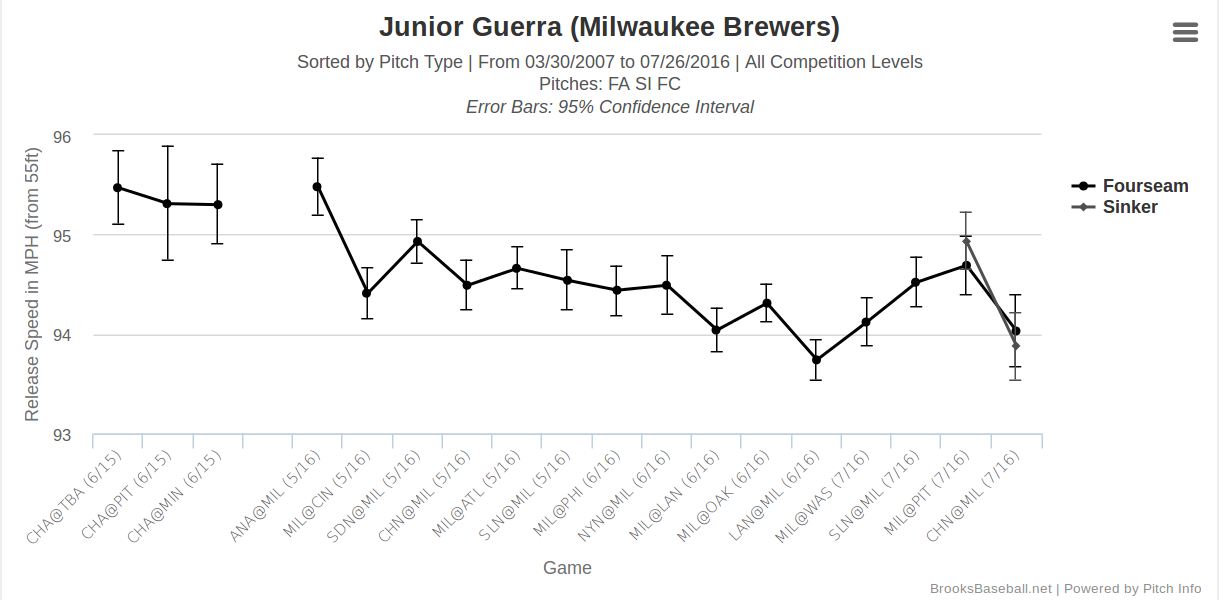

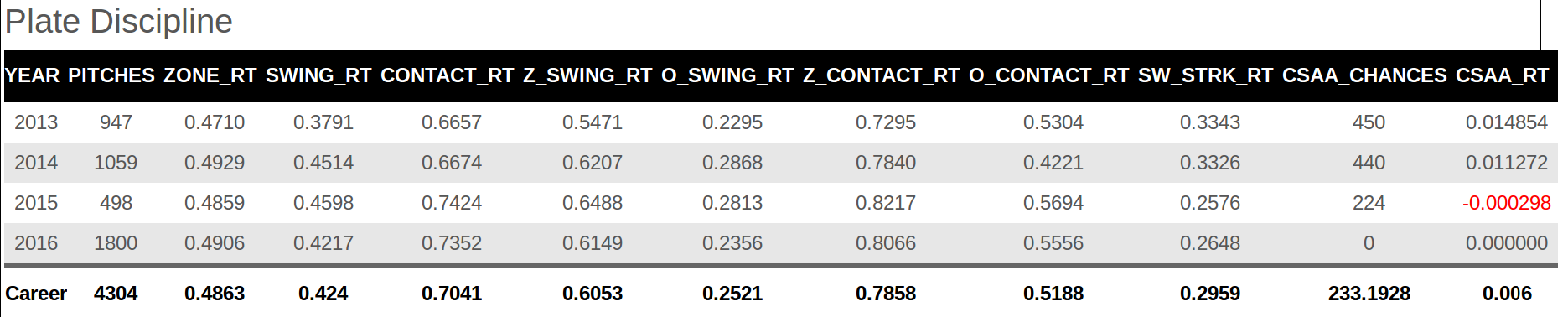

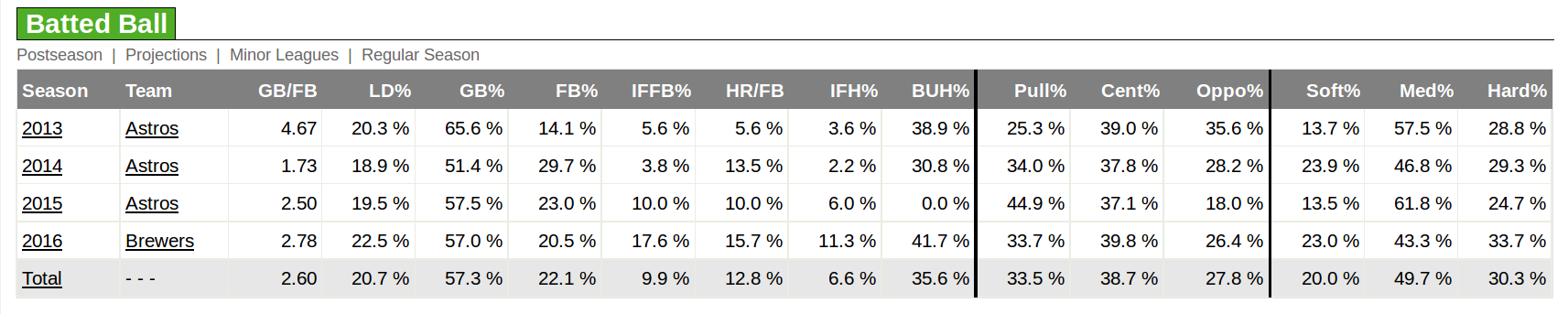

I wrote earlier this season about why pitchF/X data shows that Guerra is not a flash in the pan. But since then, two further developments have solidified my belief that Guerra will have a successful career in his thirties.

The first development happened in late June. Guerra took the mound against the Los Angeles Dodgers on the 16th and turned in his worst start of 2016: the Dodgers chased him in the sixth inning with five runs to his name and just four strikeouts under his belt. Since Scott Kazmir was similarly off point, the Brewers won an 8-6 slugfest, but that was owed more to the offensive fireworks of Chris Carter and Jonathan Villar than Guerra’s work. Less than two weeks later, Guerra drew the Dodgers as his assignment once again–and he altered his game plan in the gutsiest way imaginable. He all but cut his best pitch out of rotation. Guerra threw 109 pitches in shutting out the Dodgers over eight masterful innings, and only two of those pitches were splitters. It was a true pitching gem–Guerra’s 18-pitch first inning was the most laborious frame he suffered through, and he carved apart the Dodgers like a hot knife through butter. I have no idea what Guerra saw in the Dodgers during that first game, but I’m beyond impressed with the adjustment he made. Eliminating your “out” pitch against a team that just hit you hard is the kind of crazy tactic that you only use when you’re dead sure you spotted a weakness. That Guerra is capable of this kind of gamesmanship is encouraging, to say the least.

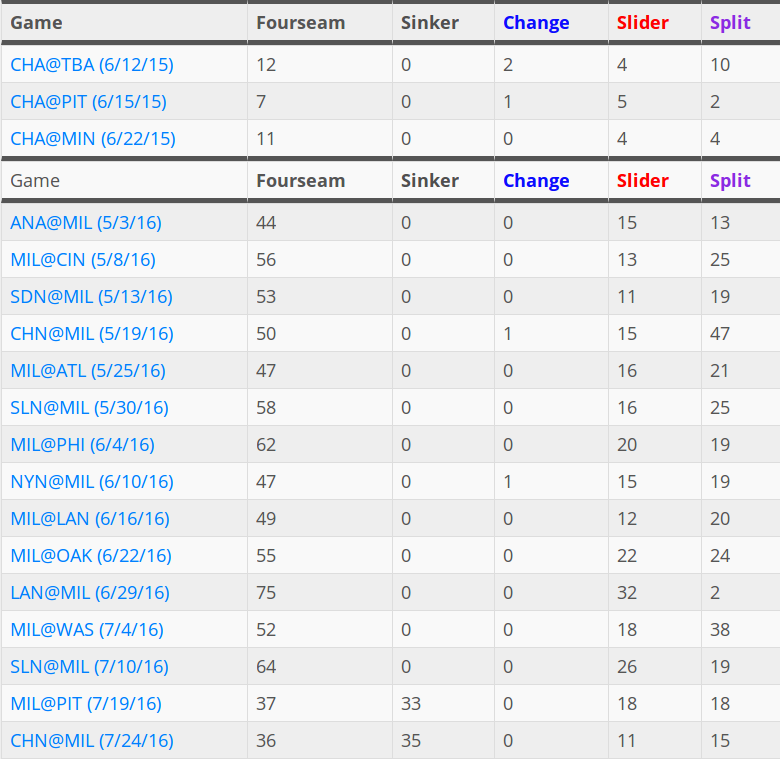

Guerra’s second adjustment came at the All-Star Break. In the first half, he threw a four-seam fastball and slider in addition to his signature splitter. But in the nine days between his last first-half start against St. Louis, and his first second-half start in Pittsburgh, Guerra had the time to add a secret weapon to his arsenal:

Ironically, it was adding a sinker to the mix that inevitably doomed the career of Wily Peralta, but we have to remember here–every ballplayer is different. And thus far, the sinker experiment has worked. Guerra fanned six in six innings against the Pirates in his first start of the half, then outdueled the far-more-expensive Jon Lester in his second try before the bullpen blew the game.

The sinker is an ideal pitch for Guerra to add to his arsenal, as it serves as a perfect blend of his best two incumbent options–the fastball and the splitter. Guerra’s sinker is indistinguishable from his fastball until it drops:

Guerra has a new weapon in his arsenal, but more importantly, he’s shown that he can adapt on the fly at the big-league level. That’s very big, and it’s very good if you’re a Brewers fan.

1. Jonathan Villar

Okay, maybe we’re cheating here by some people’s definitions. Villar wasn’t technically “free”–to pry him from the Astros cost Milwaukee a minor-league pitcher named Cy Sneed. But I would counter that Sneed was not, nor did he ever show any indication that he would turn into, an “asset.” He might not have been “nothing,” but he also held no tangible value.

The 25-year-old Villar hadn’t put up great numbers in three partial seasons with Houston, but his power/speed combination at a position of scarcity made him a valuable asset. Still, with names like Jose Altuve and Carlos Correa entrenched into the lineup, and even Luis Valbuena and Marwin Gonzalez winning favor over Villar, there was no real place for him in Houston. Last year, at this point in time, Villar was playing minor-league ball.

Two pieces of information from before the Villar trade are worth noting. First, he got back to the big leagues when rosters expanded in September and went 8-for-25 with three steals in limited action, while striking out just twice. Second, Brewers’ GM David Stearns was working in Houston’s front office while Villar was playing for Houston’s farm system last year. Publicly-available advanced analytics for minor-league players are still pretty spotty, but there’s no doubt that Houston’s modern-thinking front office is tracking everything on every player in that system. Stearns was one of the few people in baseball with the ability to accurately tell if Villar had made the kinds of structural changes that could turn him into an offensive weapon.

Villar wasted no time making his presence felt in Milwaukee. Though the Brewers pitched Wily Peralta on opening day, and therefore got beaten into a pulp, he took Madison Bumgarner deep in his second at-bat:

And since then, he hasn’t slowed down. Villar’s .297/.379/.437 slash line, paired with a league-leading 36 stolen bases, makes him the prototypical leadoff hitter, and the peripherals back it up, too. Villar’s 2015 and 2016 contact rates are significantly higher than the two years prior. The implication we can take from this is that, sometime during his minor-league exodus, he made some type of mechanical tweak that resulted in not just more contact:

but better quality contact, too:

Detractors will point to Villar’s .400 BABIP as an unsustainable mark. But just how unsustainable is it? Villar’s 57 percent groundball rate should, in theory, be killing his BABIP–only he’s also put up a silly 11.3 percent infield hit rate. Coming up through the minors, Billy Hamilton’s track-star speed was supposed to revolutionize the leadoff position–today, as it turns out, Villar is doing it instead. The Brewers gambled that, at just 25 years old, the rough edges of his game could be refined down, and it’s a gamble that has paid off with a genuine star–Villar’s 3.0 WARP places him snugly between Jonathan Lucroy (3.1) and Ryan Braun (2.9). It goes to show you that, even in the age of advanced analytics, one team’s trash can be another team’s cornerstone.

1 comment on “Seven Free Brews”