Dear Reader: I have yet to cover the incident involving Josh Hader’s offensive Tweets at BP Milwaukee for several reasons. The issue is particularly tricky given the political climate of the USA; the polarization of attitudes and ideologies regarding race, gender, sexual orientation, and society’s structures and institutions; the nature of how the Tweets were uncovered (this is less important than the first two concerns, but it matters in terms of coverage); the nature of the punishment involved (i.e., how can clubs be expected to respond?); the implication of the Brewers (i.e., how ought players act on social media when they openly share their name and identify a corporate employer?); and, of course, the fleeting nature of the news cycles. There have been several constructive conversations about Hader’s behavior on other Milwaukee Brewers websites and podcasts, as well as some national sources, and I wanted BP Milwaukee to join the conversation in a constructive manner.

I am writing this introduction to emphasize my respect for readers’ wishes not to encounter political topics at BP Milwaukee. I have weighed this heavily, due to the impact of some previous features that leaned political in my writing career both here and elsewhere. Since I believe this is an issue with great societal significance, and is deserving of lasting conversation, I respectfully invite readers who wish not to encounter political content to stop reading after this note. I respect your wish for baseball content at BP Milwaukee, and in that case turn you to our recent in-depth trade deadline coverage, prospect discussions, and analyses (as well as our forthcoming posts that will return to baseball tomorrow).

We can all hope that fewer analyses about topics like this will need to appear for future generations. My hope is that open, analytical, empirical discussions will help forge that future.

Milwaukee is a deeply segregated city. But that line has become something of a throwaway, a truth that was deeply ingrained by the early 1990s and remains true to this very day; a fact so true that residents can now utter it with resignation as frequently as they utter it with disdain. It is worth revisiting the structure of Milwaukee’s segregation because what is crucial about racial segregation in Milwaukee, as in other rust belt cities, is that racial segregation is delivered alongside harsh income segregation and stratification. These dual forms of segregation are evident in Chicago, Detroit, and Buffalo, among other cities, and even a legacy of so-called Sewer Socialism could not deliver the necessary infrastructure and policies to avert racial and income segregation in Milwaukee. While this feature will not have the space to detail each and every opportunity impacted by the correlation between income and racial segregationist policies, detailed social sciences fieldwork from Milwaukee are effectively analyzing this spiral of despair (this famously includes Matthew Desmond’s Evicted, which revolutionized social science survey methodology for studying eviction; Brenda Parker’s Masculinities and Markets uses field work in Milwaukee to demonstrate raced and gendered impacts of professional development trends beginning in the latter half of the Twentieth Century).

What does this have to do with the Milwaukee Brewers and Josh Hader? There are several concerns regarding this question. The first, and most important problem, with the content of Josh Hader’s Tweets is that most fans and commentators wrote off the content as a one-off instance of prejudicial behavior, ignoring the institutional and social structures that underlie racism, sexism, homophobia, and misogyny in the USA. The second problem involves Hader’s association with the Milwaukee Brewers on his Twitter handle, whereby Hader’s actions as a teenager were now linked to the organization through his profile. This issue is typically dismissed by a statement about linear time, where a commentator will note that Hader wrote these Tweets prior to his employment with the Brewers, ignoring the flat, instantaneous, almost timeless realm of social media. The devastation of these Tweets emanated from the content, which was extremely hate-filled, duplicated almost endlessly for hours on the national stage of the MLB All-Star Game, where the Brewers as an organization were suddenly in line to answer about the actions of a teenager; the linearity of time cannot simply alleviate the Brewers’ responsibility for this content (through a social media policy) or Hader’s responsibility for this content (through his moral conscience and development as a person). If Hader had truly changed as a person, and was truly sorry about his past, those Tweets would not have existed to be plundered during the All-Star Game.

Thus exhausts the second claim, but with this feature I would like to analyze the first concern in depth: by dismissing Hader’s actions as an instance of individual prejudice, Brewers fans and national commentators alike are severing Hader’s actions from the community in which he works. This is quite a large concern for an organization like the Milwaukee Brewers: an organization that accepts significant public subsidy for their operating expenses at Miller Park; an organization that sells its public subsidy as a tool for economic development within their community and (or) region; an organization that ostensibly is service-oriented through a notable Community Foundation. Make no mistake about it, the impact of the Brewers’ community footprint can be easily broadcast and publicly noted, as evidenced by their commitment to the Roots for the Home Team program that links urban farming and youth employment initiatives to the supply chain for MLB stadia; while this is a small program with a small impact, its positive potential and implications for MLB clubs rethinking their ballpark supply chain should not be undersold. My contention is that the Milwaukee Brewers can, and should, implement the same types of positive practices within their broader community in response to the Josh Hader incident; this is an opportunity for the organization to grow a robust, transparent, and public process for working within underserved communities in Milwaukee.

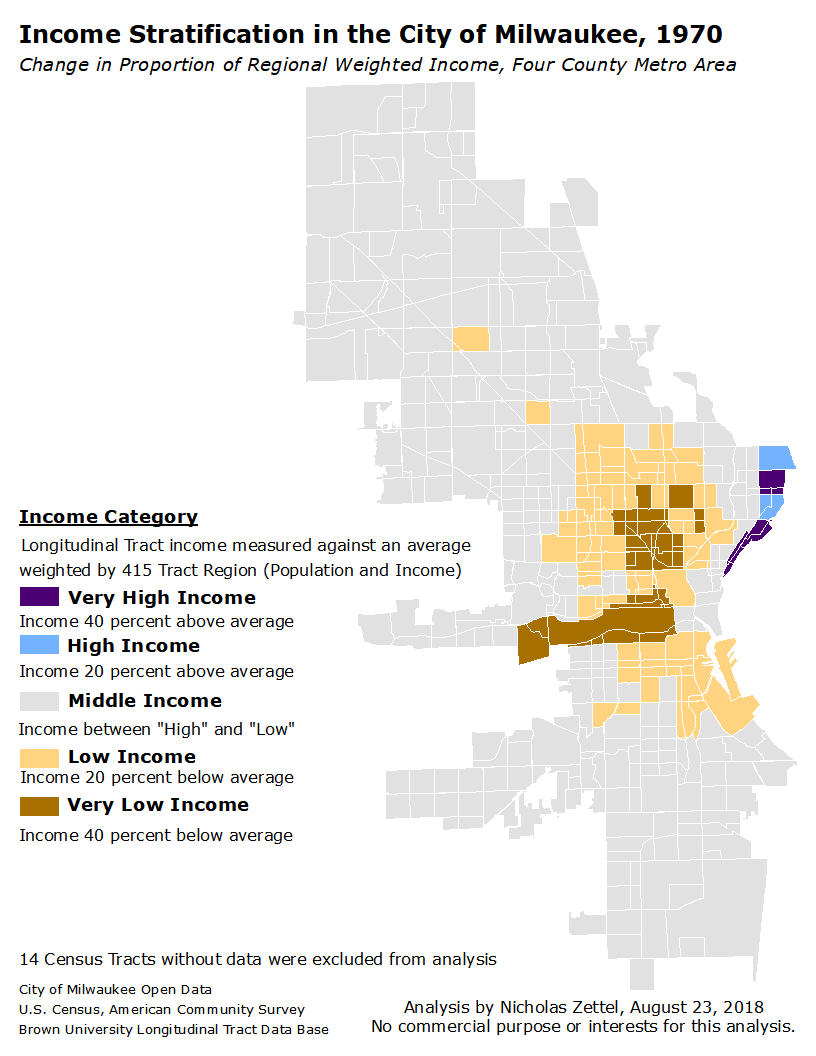

Why does this matter? In 1970, when the Milwaukee Brewers were officially born, the City of Milwaukee was largely middle income. Using longitudinal Census Tract data for a 415 Tract (see references for Hulchanski; Nathalie P. Voorhees Center), four-county metropolitan region demonstrates that 303 Tracts were classified as “middle income,” meaning that the average person living in one of those Tracts maintained a share of income between 20 percent above and 20 percent below the regional weighted average. In other words, 73 percent of the greater Milwaukee metropolitan region was middle income, and the highs and lows were relatively evenly distributed; 21 Tracts featured income 40 percent (or more) above average, while only 11 Tracts featured income 40 percent (or more) below average.

Mapping these data using longitudinal Census Tracts, here is how income was approximately distributed across the City of Milwaukee when the Brewers came to town:

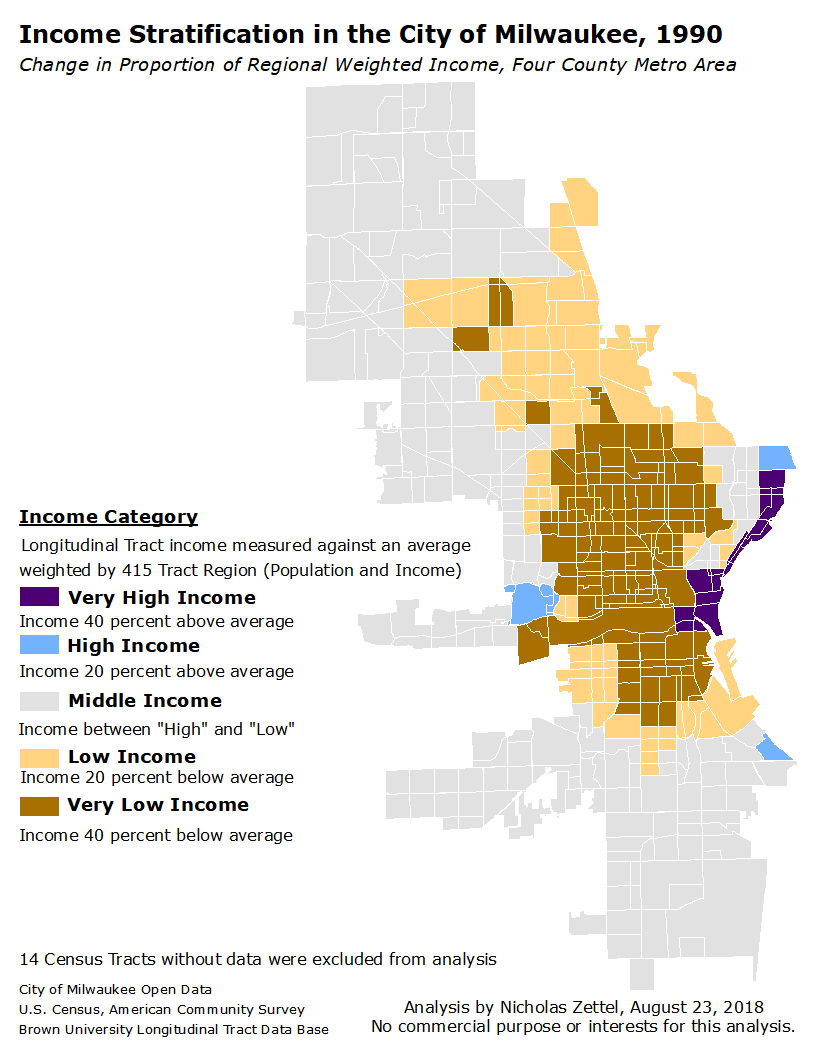

By 1990, opening a decade of rumblings about a new stadium for the beloved Brewers, following a decade of Harvey’s Wallbangers and other competitive teams, income stratification after the industrial reorganization of the City was already evident. In my experience of Milwaukee, I feel very fortunate to have been part of a busing program in which I attended very good schools in the center of the City, and I have fond memories of this time as Milwaukee Public Schools was implementing prideful, multicultural programming. I had no idea that the City was emptying of investment and, by extension, income. Compare this 1990 income distribution map with the 1970 version:

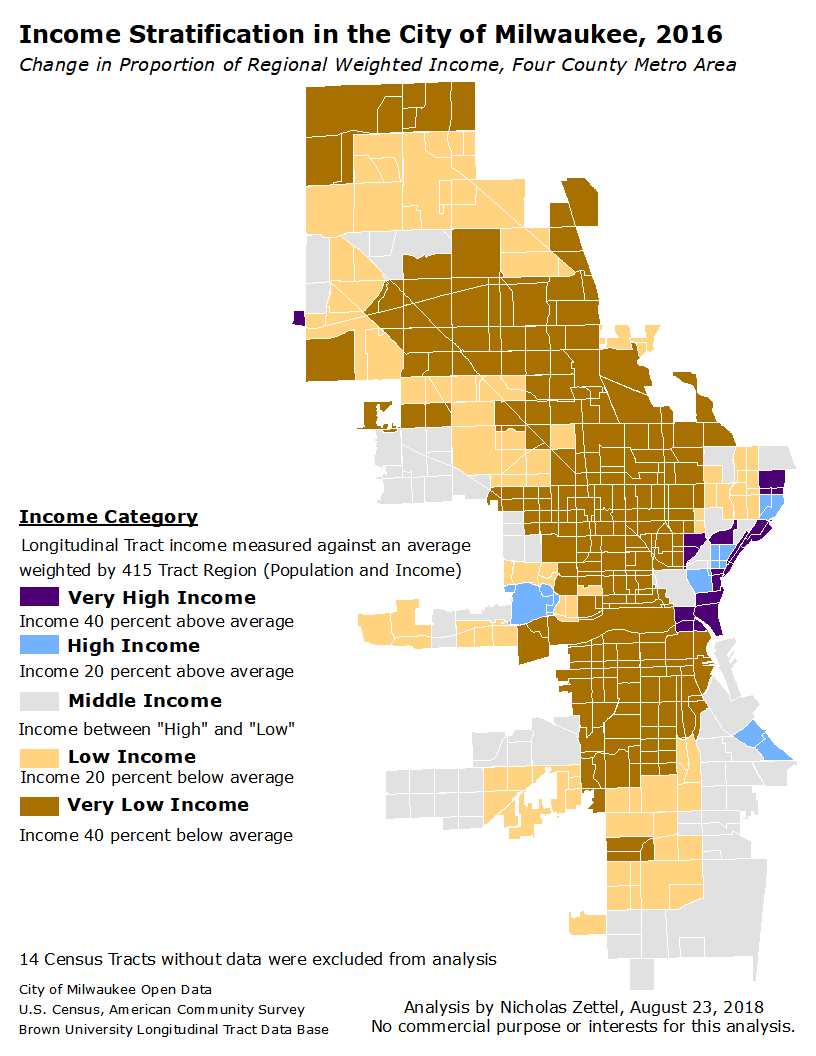

In 2016, when the Brewers were opening a new era of optimism through GM David Stearns’s rebuilding process, the investment trends of the last four decades in the City of Milwaukee roughly matched the tear-down vibes as the Brewers traded away MLB assets. This time frame also corresponds with the construction of the new Milwaukee Bucks arena, several new skyscrapers in the central business district, and a general sense that the downtown area was revitalized with condominiums and other forms of investment. Contrast the sense of downtown optimism with a city that was devastated by decades of disinvestment and aimless local, state, and Federal policy efforts:

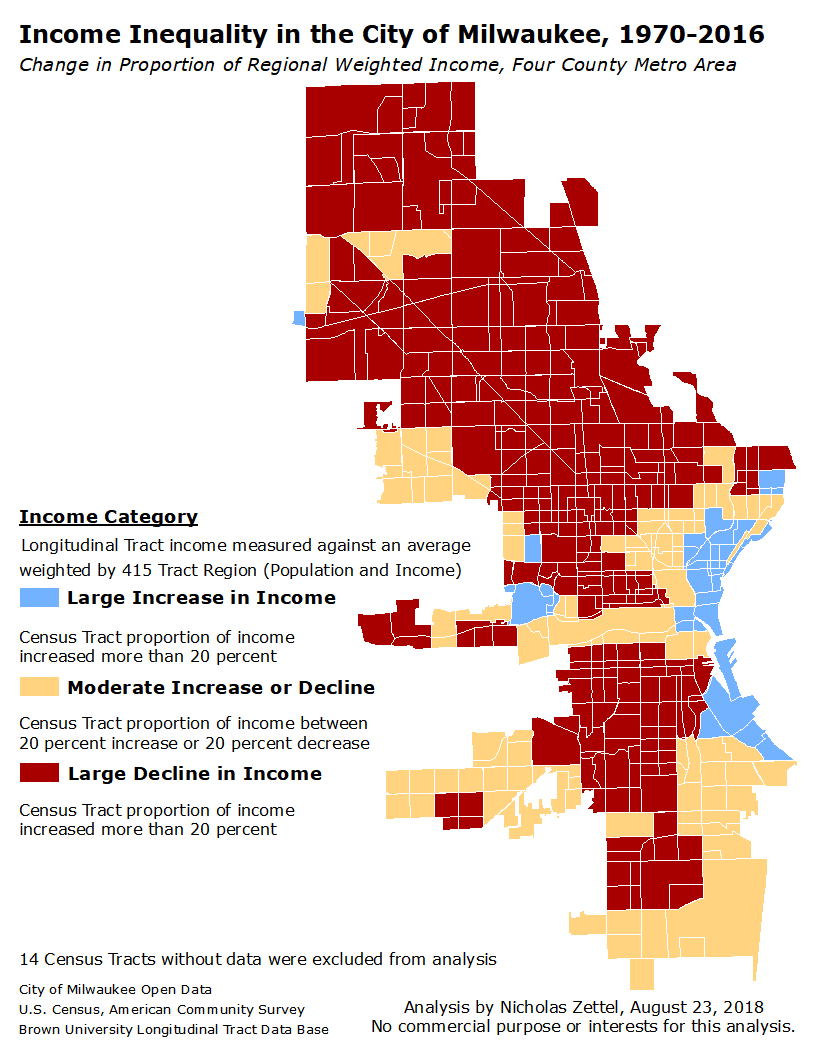

There are many stories that can simultaneously be told about the last five decades of urbanization in the USA, and in this regard the current political environment should be viewed as logical completion of this era, rather than some anomaly. Over the course of five decades, a combination of structural-institutional policies decimated cities, including mortgage insurance Red-Lining (which denied mortgage insurance to areas in which minorities, most frequently Black or African American, lived, thereby stopping formal investment in those areas), industrial restructuring and capital flight from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt, technological reorganization, and formal austerity policies at local, state, and Federal levels that sought to systematically cut services while stripping cities of their greatest public assets (such as Milwaukee’s highly-regarded sewer system).

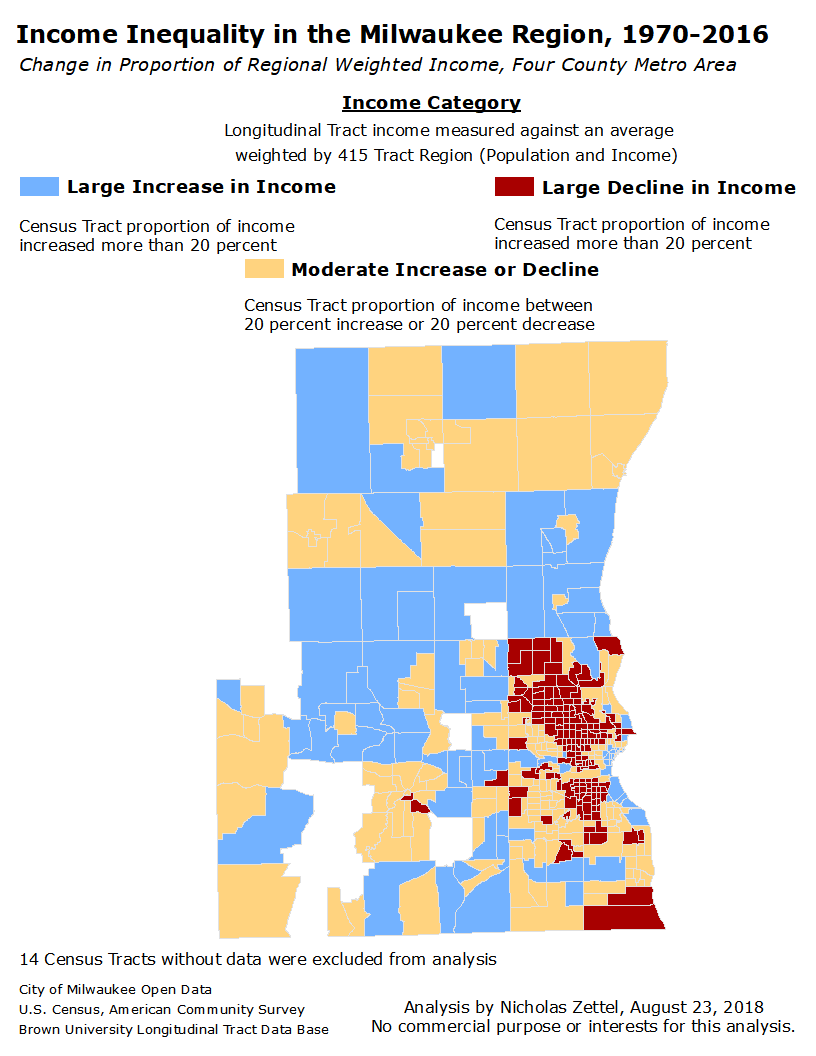

The dismal results of this reorganization of social and institutional norms produced urban landscapes of declining income, as evident in Milwaukee from 1970 to 2016; this map should be read as the five decade culmination of the preceding maps:

These practices were not only directly targeted against low-to-moderate income people, but also against racial and ethnic minorities. Viewing American Community Survey race and ethnicity estimates from 2012-2016, one can find that the culmination of extreme income stratification in Milwaukee corresponds to the culmination of extreme racial and ethnic segregation.

Table One: 2016 Estimates of Race and Ethnic Origin Based on Analysis of Four-County Milwaukee Metropolitan Region Income Categories

| Census Tract Category | Population | White / Not Hispanic | Black or African American / Not Hispanic | Asian / Not Hispanic | All Other Origins / Not Hispanic | Hispanic or Latino Origin / All Races |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Increase in Income | 22.3% | 89.0% | 2.0% | 4.0% | 1.7% | 3.4% |

| Moderate Increase or Decline | 43.3% | 81.8% | 6.0% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 7.6% |

| Large Decline in Income | 34.4% | 32.8% | 40.7% | 4.5% | 3.0% | 19.0% |

Most Milwaukeeans understand this divide in their hearts, or face it in their daily existence, but it is worth systematically analyzing the progression and distribution of income over the last five decades in order to demonstrate the impact of segregation by race and class. Across the four-county Milwaukee metropolitan region, the Census Tracts that experienced a large increase in income over the last five decades are overwhelming white, not-Hispanic (89 percent); the same can be said for Census Tracts that experienced moderate change in income over five decades (82 percent white, not-Hispanic). By contrast, among people living in metro Census Tracts, 40 percent are identified as Black or African-American, not-Hispanic, and 19 percent are identified as descending from Hispanic or Latino origin. Viewing the four-county metropolitan region as a whole, this stratification of income and segregation by race and ethnicity is spatially evident between “suburban” Ozaukee, Washington, and Waukesha counties, and the County and City of Milwaukee.

This is what “Milwaukee” means on the Milwaukee Brewers jerseys. Milwaukee can be many things, of course; Milwaukee could be an ideal of working class success, an immigrant success story on the (then) western frontier of the USA; Milwaukee could be beer, signifying the strength of the brewing industry that remains evident across the infrastructure and buildings of the City; Milwaukee can be what we lost, a symbol of the lost industrial grind; Milwaukee could be Wisconsin’s resurgent urban gem, a chance to demonstrate innovation in environmental policy and affordable housing development (both of which are happening); Milwaukee can be home, or a birth place (this is why I wear my Milwaukee Brewers hat across Chicago, for although Chicago is now my home, Milwaukee is where I was born, and this is important and evident for reasons other than when I order a bagel). Milwaukee can be all of these things, but you cannot construct an image of the city, or the region, without grappling with the devastating policies of the last five decades and the subsequent income stratification and racial segregation.

What can be done? I understand that I have only spoken to one aspect of Josh Hader’s Tweets, and I don’t mean that to diminish the importance of fighting for gender equality and sexual liberation. Frankly, I focused on the concerns of income inequality and racism first and foremost because there are clearer ways to build a methodology for demonstrating the outcomes of these institutional norms and social practices; it is more difficult to write about gender identity, the casualization of work, gendered division of labor, and extension of household practices into professional spaces that undergird misogyny and homophobia. I frankly do not know how to systemically examine and write about this issues in an effective way, other than to say that I greatly oppose misogyny, sexism, homophobia, and racism.

In terms of policy implications and public service, the Milwaukee Brewers have fallen short, as an organization, in their public demonstration that they oppose the spirit and practices associated with the societal message of Hader’s Tweets. To my knowledge, Principal Owner Mark Attanasio has yet to even issue a public statement about the matter (if this was broadcast and I missed it, or published somewhere and I missed it, please correct me). I personally find this baffling, especially during a time in which the Brewers are exhibiting forward-thinking practices regarding community economic development (such as the Roots for the Home Team program). It is not enough for Josh Hader to receive sensitivity training because for this punishment to be retributive, the issues evident in his Tweets would have to simply be “prejudicial” on an individual basis, rather than embedded in decades of social practices. These social practices have destroyed the City of Milwaukee, and tens of thousands of Milwaukee residents grapple with the effects of poverty, isolation, lack of services, lack of resources, and lack of occupational and professional mobility that accompany systemic income inequality and racial segregation.

This is not the Milwaukee Brewers’ issue to solve alone, but they are a large stakeholder in the region, one that ostensibly operates for the purposes of improving economic growth in the region and developing economic opportunity. If the Brewers are serious about their potential to drive economic development as an organization, they need to issue a stronger public response to the Hader incident; a response that speaks not to the content of the Tweets or the individual instances of prejudice, but one that acts against five decades of institutional neglect and disinvestment throughout their City. This is an opportunity for Mark Attanasio to place the large profits of the club’s rebuilding efforts and MLB Advanced Media pay outs to great use within the community, for even a fraction of the club’s profits would go a long way to spur public investment and service opportunities. This is bigger than Josh Hader, but he can publicly, openly support such efforts with the Brewers.

References

Brown University Longitudinal Tract Data Base. Spatial Structures in the Social Science. Retrieved May 26, 2018 from Brown University. Tables: All Full Count and All Sample.

Hulchanski, David J. “The Three Cities Within Toronto: Income Polarization Among Toronto’s Neighborhoods, 1970-2005.” Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto, 2010 (ISBN 978-0-7727-1478-7). Accessed online via PDF:

http://www.urbancentre.utoronto.ca/pdfs/curp/tnrn/Three-Cities-Within-Toronto-2010-Final.pdf

Kursman, Jessica and Nick Zettel. “Who Can Live in Chicago?” Nathalie P. Voorhees Center for Neighborhood and Community Improvement, University of Illinois at Chicago. June 6, 2018. Accessed online via blog:

https://voorheescenter.wordpress.com/2018/06/06/who-can-live-in-chicago-part-i/

Logan, John R., Zengwang Xu, and Brian Stults. 2014. “Interpolating US Decennial Census Tract Data from as Early as 1970 to 2010: A Longitudinal Tract Database” The Professional Geographer 66(3): 412–420.

University of Richmond. Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. Accessible online:

https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/ [HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!]

Nathalie P. Voorhees Center for Neighborhood and Community Improvement. “40th Anniversary Symposium: Who Can Live in Chicago?” University of Illinois at Chicago, May 4, 2018. Center Link:

http://voorheescenter.uic.edu/

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. Five-Year Estimates, 2012-2016. Retrieved August 5, 2018 from factfinder.census.gov. Tables B01001 (Sex By Age); B03002 (Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race); B19301 (Per Capita Income in the Past 12 Months).

Related Research:

Broad, Dave. 2000. “The Periodic Casualization of Work: The Informal Economy, Casual Labor, and the Longue Duree.” In Informalization: Process and Structure, edited by Faruk Tabak and Michaeline A. Crichlow, 23-46. Baltimore, MD.: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Centeno, Miguel Angel and Alejandro Portes. 1989. “World Underneath: The Origins, Dynamics, and Effects of the Informal Economy.” In The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, edited by Alejandro Portes, Manuel Castells, and Lauren A. Benton, 11-37. Baltimore, MD.: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

O’Connor, Alice. 1999. “Swimming Against the Tide: A Brief History of Federal Policy in Poor Communities.” In Urban Problems and Community Development, edited by Ronald F. Ferguson and William T. Dickens, 77-121. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Sassen, Saskia. 2000. “The Demise of Pax Americana and the Emergence of Informalization as a Systematic Trend.” In Informalization: Process and Structure, edited by Faruk Tabak and Michaeline A. Crichlow, 91-115. Baltimore, MD.: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Smith, Neil. 1984. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Weil, David. 2017. “Income Inequality, Wage Determination, and the Fissured Workplace.” In After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality, edited by Heather Boushey, J. Bradford DeLong, and Marshall Steinbaum, 209-231. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.