Brewers GM David Stearns had a wild non-waiver trade deadline to close July, and the GM once again proved that he was not afraid to deal potentially quality talent as the August waiver trade deadline was closing. As the waiver trade deadline closed, Stearns parted with college catching development project KJ Harrison (who might also be a bat-first infielder in this or another universe); change-of-scenery candidate and big International bonus infielder Gilbert Lara (who could also be a corner infielder with pop some day); veritable toolshed Demi Orimoloye (my favorite toolshed to dream on, in my favorite universe he’s a solid starting right fielder that can do a little bit of everything, maybe using that to prop up a .240 batting average); as well as a couple of Dominican Summer League flyers (Bryan Connell and Johan Dominguez).

Like the July deadline, David Stearns is giving Brewers fans transactions that can be viewed from many standpoints:

- Stearns is improving both key roles and marginal roles through both deadlines.

- Stearns is arguably stockpiling as much talent as is physically possible (within the constraints of the 40-man roster).

- The GM is dealing prospects with lofty Overall Future Potential (OFP).

- The GM is dealing ultimate roles that may be blocked (Brett Phillips), uncertain (Jorge Lopez), or years away from fruition (this can apply to everyone from Jean Carmona to Orimoloye, Lara, Connell, Dominguez, and Harrison).

- Stearns is looking toward potentially longer outlooks by acquiring several players with 2019 options or roster reserve rights.

This is a lot to take in, and frankly it’s made it difficult to write about the trade deadlines in one swift motion. For on the one hand, by estimating long term value of some of the roles traded away, it appears that Stearns truly did overpay in several deals in order to succeed within a short window. Yet, it’s not entirely clear that Stearns traded away anyone that was fitting into Milwaukee’s immediate window. It pains me to say this even with strong prospects like Brett Phillips, or serviceable roles like Jorge Lopez (one of my favorite pitchers in the system for a long time). As much as I love to use depreciated surplus value to assess trades, since it is a tool that attempts Benefit-Cost Analysis on players’ production and contract, Stearns is providing a clear template for critiquing moves outside of any WARP/$ framework.

Specifically, by moving clear MLB players from a small market club that ostensibly requires cost-controlled, easily reserved talent to win, Stearns’s deadline provides an excellent opportunity to survey the uneven landscape of player development. In this regard, it is worth noting that no trade can truly meet WARP/$ standards, because in the universe of player development a pitcher can add a new pitch or rework their mechanics, a batting can revise a timing mechanism or refine a swing, a player can fall under the influence of a new coach (for better or worse), or a player can simply experience a new environment in which opportunities shift. Information asymmetry is the landscape of player development, and thus MLB transactions, and in this regard no deal can ever reach equilibrium between parties, as both teams involved in a given trade will arguably be assessing players through different environments (this argument has hidden behind my work on depreciated surplus, but surfaced in a demonstration with the Brian McCann trade).

On Tuesday, another one of the prospects dealt away from Milwaukee acquired a true MLB floor as well, as the Baltimore Orioles selected the contract of RHP Luis Ortiz (traded away as the lead prospect in the Jonathan Schoop deal). Now, the “surefire” MLB players that one could have assessed from the July deadline deals are all in The Show (Brett Phillips and Jorge Lopez are in Kansas City, and Ortiz is now in Baltimore). I will not be focusing extensively on Phillips’s case here, as he is doing pretty much what could have been expected on the day of the trade: starting in center field (21 of 26 games) and right field (4 of 26 games). Lopez and Ortiz, however, offer completely asymmetrical development from the Brewers’ system, and this is worth investigating because the Brewers have what is justifiably regarded as a strong pitching program, due to their track record in 2017 and 2018 (yes, in 2018!), oft-praised coach (Derek Johnson), and their unorthodox pitching acquisitions that appear to follow very specific profiles (this applies to everyone from Oliver Drake to Chase Anderson and Zach Davies, among others). Answering questions about Lopez and Ortiz may help to address other bizarre roles in the 2018 pitching system, most notably involving Brandon Woodruff, Adrian Houser, and even (arguably) Corbin Burnes.

First, let’s establish two role discrepancies that may be the result of different organizational interpretations of information:

- Jorge Lopez has already started four games for the Kansas City Royals, boasting an 18 strike out / eight walk / two homer / 37 percent ground ball profile (4.86 Deserved Run Average). He has alternated good and bad starts thus far. However, the Brewers failed to use Lopez as a starter in 2018, instead employing Lopez as a successful member of the Triple-A shuttle team between Milwaukee and Colorado Springs; this mirrors Lopez’s 2018 minor league role (reliever) and follows his organizational shift to relief role in 2017. Despite what may be viewed as a spotty command profile and a lack of a deep pitching arsenal, the Royals promptly started Lopez and have him shifting sinker / riding fastball and slider offerings to “re-balance” his approach.

- Luis Ortiz battled some injuries and stamina concerns during his time in the Milwaukee organization, which spanned 44 games at Double-A Biloxi across parts of three seasons. Ortiz was mostly a starter in the Milwaukee organization, building his innings pitched total to career highs in three consecutive seasons; the righty is now at 99.7 innings and counting upon entering the MLB. Upon acquiring Ortiz, Baltimore assigned him directly to their Triple-A Norfolk club, and now are selecting his contract for a September showing. One might surmise this is to help boost his innings pitched total closer to 120.0 IP by season end, setting the youngster for a perfectly respectable workload floor for 2019.

Since I do not have additional, unpublished scouting information on Ortiz from his short time in the Baltimore organization (and there do not appear to be any updates from Norfolk), I am going to simply note that according to his minor league game data, there is no discernible statistic that demonstrates why the Orioles might recall the prospect. Alternately, there is equally no discernible argument as to why the Brewers did not view Ortiz as an immediate depth option to potentially bolster a contending pitching staff (and their aggressive handling of Freddy Peralta supports that question).

On Ortiz, the following table is from Baseball Reference CSV:

| 2018 Luis Ortiz | PA | GB% | FB% | LD% | PU% | K% / BB% / HR% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biloxi (AA) | 288 | 33.0 | 36.5 | 13.2 | 3.8 | 22.6 / 6.3 / 2.4 |

| Norfolk (AAA) | 135 | 31.1 | 48.1 | 14.8 | 5.2 | 15.6 / 5.9 / 3.0 |

I would like to reject the “Orioles have nothing to lose” argument for recalling Ortiz, and I’d apply that same reasoning to the Royals, as well. For example, the Brewers apparently have everything to lose in 2018, and they entered the season with Jhoulys Chacin, Yovani Gallardo, and Wade Miley as their major pitching acquisitions for a year in which they probably suspected Jimmy Nelson would miss substantial time. The point being, “having something to lose” has not kept the Brewers from making unorthodox development moves and acquisitions, and that applies equally to starting Freddy Peralta ahead of top pitching prospect (and much clearer starting role) Corbin Burnes as it does to Chacin, Gallardo, and Miley. For goodness sake, the club just recently acquired veteran southpaw Gio Gonzalez, a starting pitcher by trade, and then mentioned that they might not use him as a starter. So, it is clear that “having something to lose” is no motivator for the Brewers to make “expected” or orthodox pitching moves; relative position in the standings should not explain these player development moves.

The flipside of this argument, I will add, is that this should not be taken as a “Derek Johnson is magic” argument, either. I do not believe that Brewers fans and analysts should fall back on that argument, because it basically substitutes a new type of devotional thinking about pitching development for previous orthodox thinking about pitching roles, and solely using a coach’s successful cases for transactional justification is a bad thing. Those of us relying on public knowledge will not understand or know any of Johnson’s potential “failures” in terms of mechanical or arsenal adjustments among Brewers pitching. Furthermore, this type of magical line of argument about Johnson’s skills could thus theoretically justify any pitching acquisition, which should be viewed as ridiculous on the face of it. For example, none of us should be rummaging the lowest DRA of 2018 simply to argue “x, y, and z should be Brewers targets because of Wade Miley and Derek Johnson,” and that’s not meant as a knock on either Johnson or Miley.

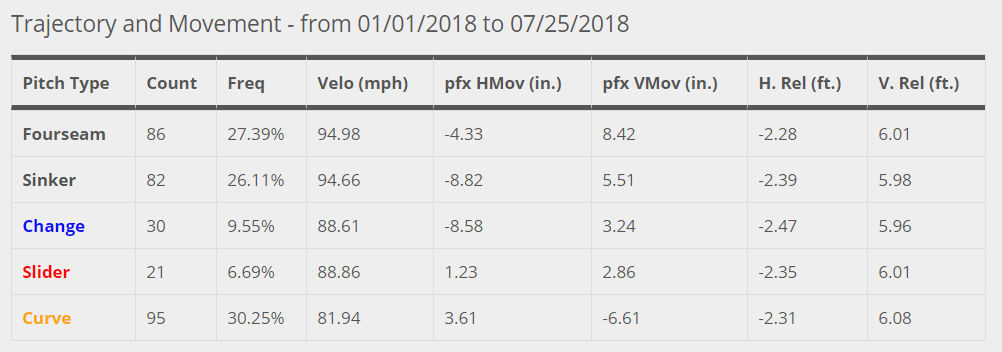

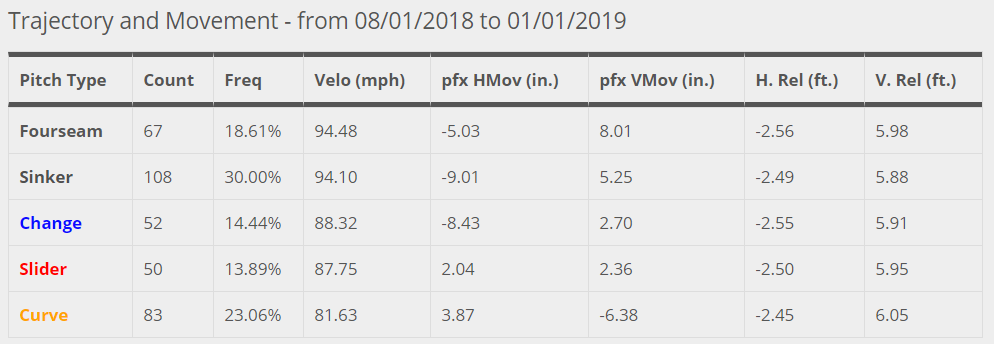

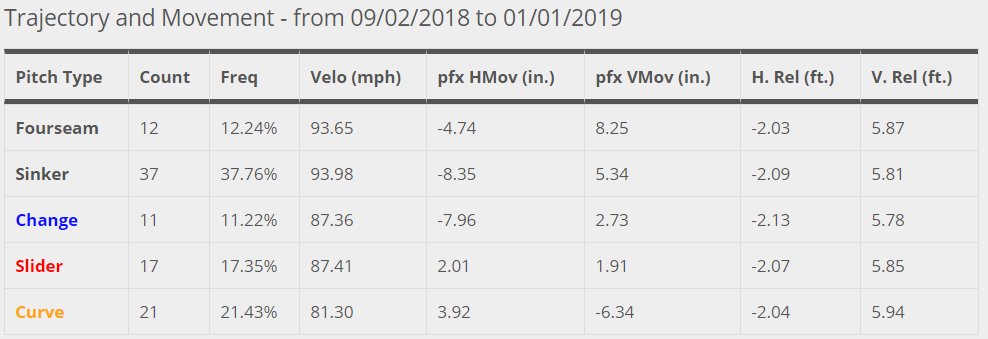

Jorge Lopez, on the other hand, has provided new data as a member of the Royals, and the righty is demonstrating a complete shift in his arsenal. Brewers fans will recall that Lopez used his big, tall frame to generate a fairly traditional rising fastball, curveball, change up arsenal. During Lopez’s time in Milwaukee in 2018, the Brooks Baseball classification system captured a “sinker,” which might also be called a riding / running fastball (although the vertical movement readings on the pitch hint that it may actually be a sinker). Lopez also introduced some variation of a slider:

Thus far in Kansas City, Lopez has reoriented this arsenal by reducing his “primary fastball” in favor of his sinker and slider. Along with these noticeable moves, Lopez is also ticking up his change and curve slightly.

Lopez has had two rough starts, but his most recent start against the Orioles was the best of his young career. In this start, perhaps Lopez cashed out the most extreme version of his arsenal adjustment, working sinker or slider for nearly 55 percent of his deliveries. Yet that curve still figures prominently at 21 percent of his overall selections, meaning that Lopez could also be called a sinker-curve guy.

This new arsenal is a fantastic look for Lopez, and it raises a difficult question that is worth asking, but must be asked in the proper critical mindset and organizational vantage point: when is a pitcher simply a new pitch, or a re-balancing of their arsenal, away from success? When is a pitcher simply in need of an opportunity? I hinted at this question following the July trade deadline, as the Brewers traded a pitcher who might be dismissed as “merely serviceable” at a time of increased need for quality depth due to injuries and ineffectiveness. Yet the Brewers did not give Lopez a start, nor did they keep him as a fixture in the bullpen, perhaps as a multi-inning guy. I don’t mean this as a criticism of the Brewers, however, because one could have reasonably asserted at the time that previously lofty goals of Lopez’s rotational Overall Future Potential were a thing of the past; here we are, though, with the tide potentially shifting within the Royals rotation.

The least satisfactory answer is that the Brewers simply missed on Ortiz and Lopez. Perhaps they were so cautious with Ortiz as to miss the potential upside (or even the current MLB floor!) in his profile. One could have said on deadline day that Luis Ortiz was maybe two or three years away from being a true impact, Number Two starter (if he were to reach his ceiling); perhaps that logic misses the value of how good a low rotation floor can be on many days in the MLB (cf. the 2018 Brewers, from Wade Miley to Freddy Peralta and, yes, even Junior Guerra most days). A more realistic answer, and perhaps the Lopez development supports this, is that maybe Milwaukee simply was not the place for these developments; even the acquisition of Jake Thompson and Jordan Lyles suggests that Stearns may have already found other development projects that better fit the organizational plan.

It is interesting to work with these unsatisfactory, vague conclusions while designing a framework for assessing Brandon Woodruff’s future with the organization, or even the potential future role for someone like Wade Miley:

- Is Miley a Brewers pitcher now, worth a contract extension and a trip back to the well, a celebration of a job well done and certainly a job worth tens of millions of dollars?

- Is Woodruff, about as bread-and-butter middle rotation starter / potential impact relief profile as one could ask for, a pitcher with a steady rotation or bullpen future in Milwaukee?

- With the continued development of Adrian Houser as a starting pitcher in the minor leagues, is Houser already poised to become the MLB starting role recovery for the Brewers that Jorge Lopez was not?

The trouble with these questions is that they could be answered in different ways for different organizations, but the benefit is that the Brewers currently reserve an crucial opportunity to learn from their recent transactions and maximize their development approach with each of these pitchers.

Photo Credit: Denny Medley, USA Today Sports Images

I get that DJ may have helped a few starters (Anderson, Guerra, etc.) establish or legitimize themselves in the MLB, but I am wary of this devotional thinking you mention that I see online. I also don’t see this narrative that people are ascribing to him and the Brewers’ system as keen developers of pitching, because I don’t see it having translated to results yet. A deep playoff run built on the backs of their mediocre-on-paper staff would probably change my mind, but what has this staff really accomplished under DJ’s watch?