In 2014, the baseball world entered the realm of replays. Before, one could only review home run balls, but now, teams can review any play on a baseball field that isn’t a ball or strike. In order to review a play, however, a manager needs to challenge a play. The manager only has one challenge, but if he gets the call overturned then he is allowed to keep his challenge; if he is wrong, then the manager loses his challenge for the rest of the game.

These rules are important, because they added a component of strategy. This means that data needs to be gathered to analyze the proper strategy. A few baseball sites have been gathering this type of information. The one that I will use today is the Retrosheet information.

Before anything further gets pointed out, it’s important to acknowledge that umpires are very good at their jobs. In 2015 only 48.86% percent of challenges were overturned, and in 2016 47.5% of calls have been overturned (the 2016 data only goes until June 30th).

With this new strategy, managers now have another added component to their jobs. They wield more responsibility towards the game. Therefore, let’s look at how Craig Counsell and other managers have decided to utilize those challenges.

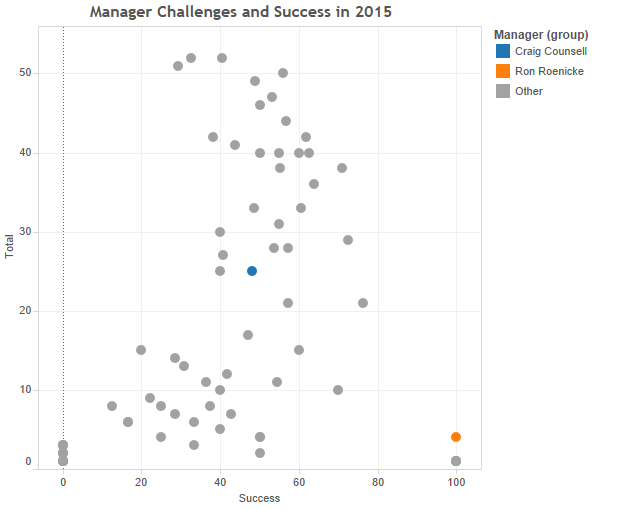

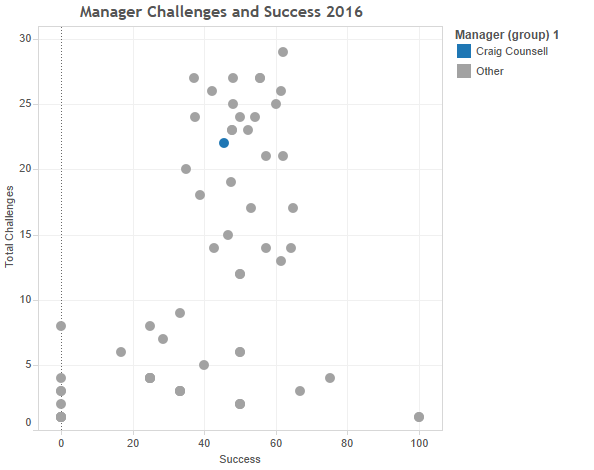

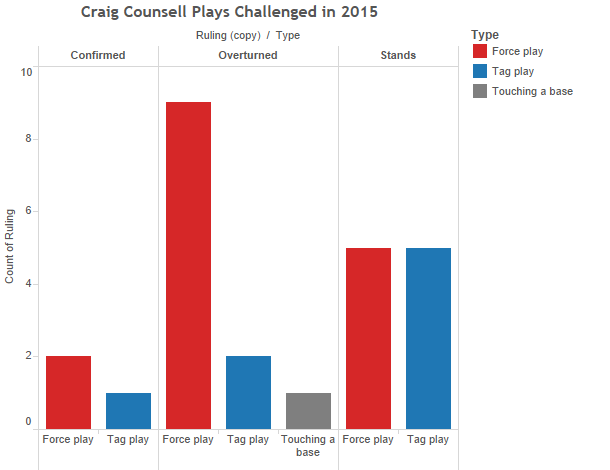

Counsell wasn’t the manager for the entire season in 2015, but he definitely used the most challenges out of the two Brewers managers. As mentioned before, in 2015 managers were successful in only 48.86% of their challenges. Counsell was right around that mark at 48% himself in 2015, but he only challenged 25 plays all year, which ranked 27th out of 74 managers who used a challenge. But, most of those are managers that barely used any challenges and are clustered at the bottom, where they’ve challenged less than ten plays, meaning that Counsell didn’t challenge many plays in 2015.

2016, however, is a different story.

Counsell has already challenged 22 plays and ranks 16th. The reason I bring this up is because it seems as though teams should be challenging more plays.

As Jesse Wolfersberger wrote for The Hardball Times:

“So, should a manager challenge a one-on, one-out play in the first inning? According to my analysis, the likely answer is ‘yes.’ I found that the expected number of any over-turnable plays in a given game is less than one. Further, the expected number of over-turnable plays that go against your team in a medium-to-high leverage situation is far less than one.

Bottom line for managers: If there is a call that you have even a 50/50 chance of reversing, you should probably challenge, no matter the inning or the game situation. The odds are, there won’t be a better time to use that challenge later in the game.”

In total, managers only used their challenges in 28.1% of games in 2015, and the Brewers only challenged plays in 20.4% of their games.

This seems incredibly inefficient. In theory, teams should probably use their challenge at least once a game. It doesn’t even matter whether they get it right most of the time. Of course, if there is a close, and critical play in the fifth or sixth inning, the manager should use his challenge, but there are a number of times when managers don’t use their challenges. Basically, managers often go through an entire game without a single challenge being used, even though it wouldn’t hurt to try to challenge a play in the eighth inning (even if it didn’t really have a good chance of being overturned).

Who knows, maybe the people reviewing the game will make a mistake.

There are obviously aesthetic reasons as to why this wouldn’t be an enjoyable way of watching baseball. More replays means more delays, which means more downtime, and therefore, longer games. But, this shouldn’t be the concern of the manager and the team; their goal is to win games.

This is a flawed system, and it’s odd that managers aren’t abusing the ability of these challenges.

It’s in many ways like the forfeit rule. As Henry Druschel pointed out, teams can use the forfeit rule when a game is basically out of reach, “Teams are almost certainly harming their long-term win rates in a meaningful way by playing until every out of every game has been recorded. For example, the Red Sox encountered a grueling quirk of the schedule on Wednesday night, when they were scheduled to play the Orioles at 7:05 p.m. before traveling to Detroit and playing the Tigers at 1:10 p.m. the next day. When it began to pour in Baltimore at roughly 9:00 p.m., the Red Sox were leading 8-1 after six innings, but imagine if the situation was reversed, and Boston was instead trailing 8-1 with three innings to go. Their odds of coming back to win such a game would be something like 0.5 percent. In such a scenario, they could either wait in the clubhouse until the game was either resumed or officially cancelled, or they could forfeit as soon as the rain began, and head for the airport and Detroit right away.”

Teams jump through loops on end to try and get an advantage, and yet, there are still aspects of the game that are done inefficiently.

Expanded replay is here to stay. Once that door was opened, there’s no shutting it ever again. But, the way replay is done can always be changed and altered. Right now, we have a challenge system. It adds a layer of strategy, but for some reason, teams seem to be more concerned with getting the play right, than to use the replay challenges to it’s potential.

Bonus:

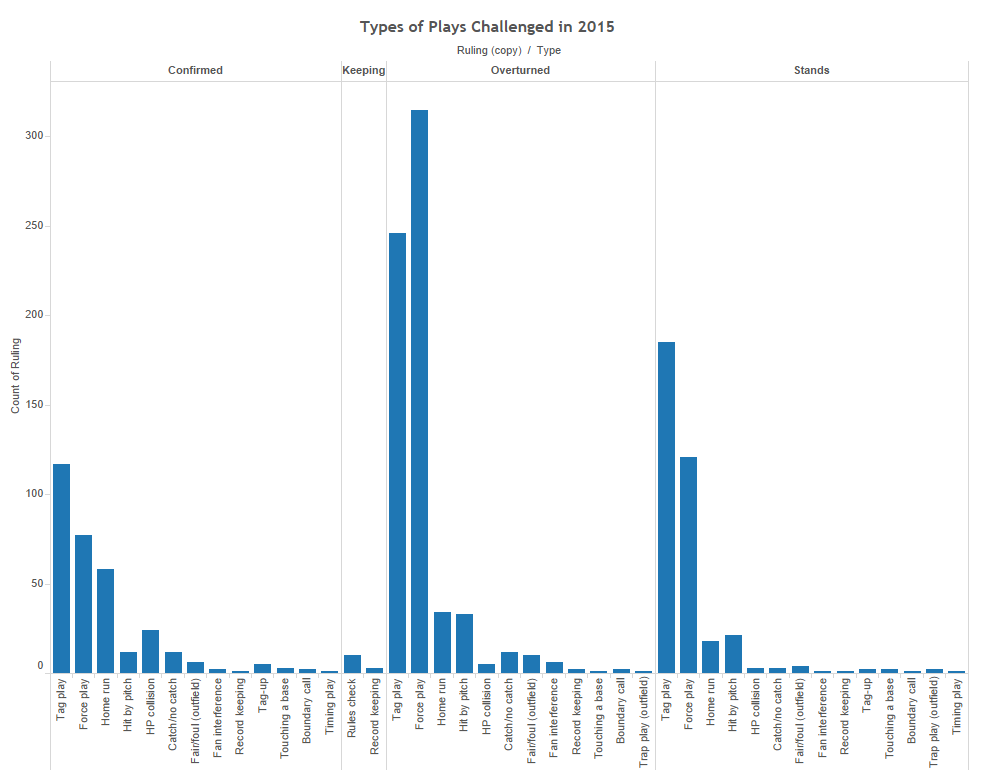

Here’s a look at which plays get challenged the most.