Last season, the Brewers led all of baseball in stolen bases by a considerable amount. They were not, however, a particularly good baserunning team, at least according to BP’s BRR statistic, which calculates overall value contributed by baserunning rather than just being limited to stolen base percentage. In 2016, according to BRR, the Brewers were 15th in the majors in baserunning despite the aforementioned lead in stolen bases. Part of that drop was attributed to a good rather than great success rate; the Brewers were sixth in stolen base rate as a team even though they had 42 more successful steals than the second-place Reds. The rest of it is due to the fact that they were not particularly smart on the basepaths. BRR takes into account ability to advance on fly balls, hits, and all other opportunities, and the Brewers were so bad at advancing on hits that it dragged down their overall ranking despite being in the top ten in all other categories.

It’s not that hard to come up with after-the-fact explanations for this discrepancy between stolen base rate and BRR; the most plausible explanation is that the team was full of fast players who were not particularly good baserunners. Jonathan Villar is a good example of this, as he led baseball in both stolen bases and times caught stealing. Orlando Arcia and Scooter Gennett were also bad baserunners despite good stolen base rates.

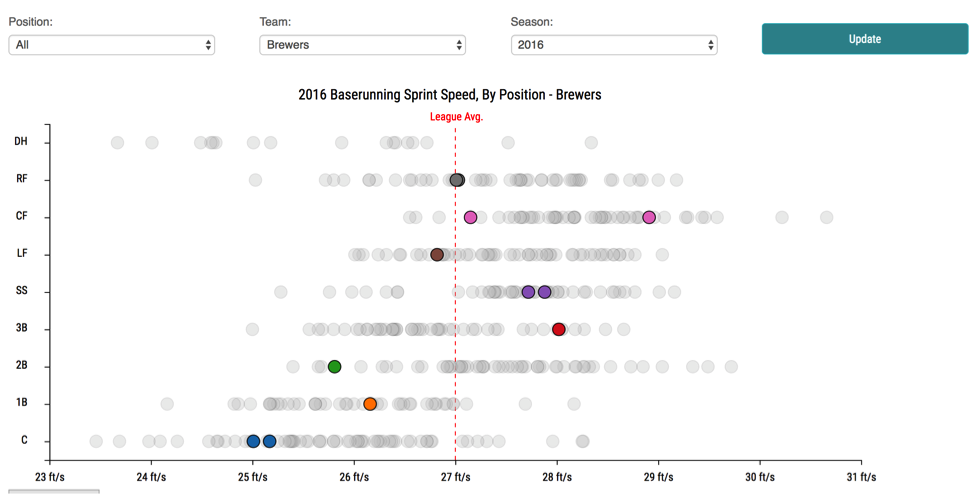

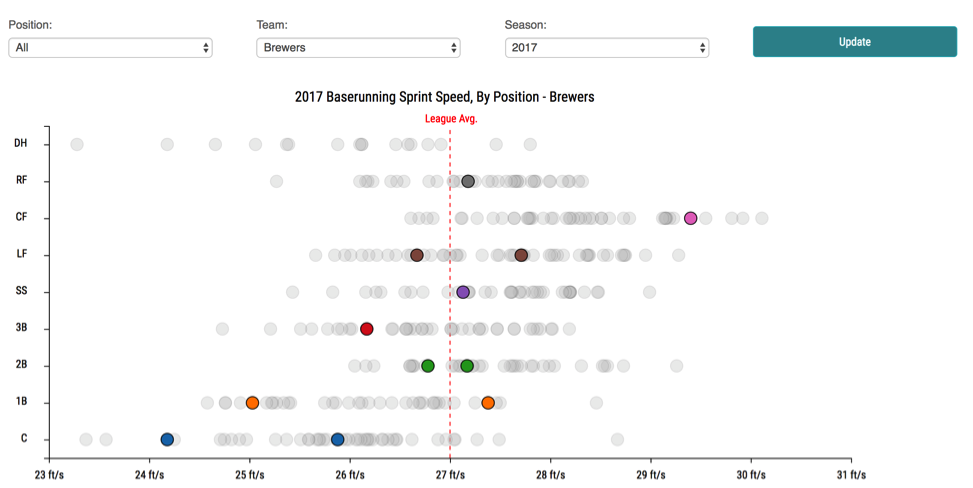

Statcast released its sprint speed metrics this week, and that provides more information about exactly how fast players are, especially relative to league average and others at their position. In its current form, the measurements are not perfect. For example, acceleration and length of sprint are just as important as raw speed, particularly acceleration in the context of stolen bases. For the time being, though, sprint speed is what we have, and it is illustrative in this context.

Two additional caveats are necessary at this point: I do not know what sample size is needed for these numbers to stabilize, nor do I know what types of variations are normal. However, it seems logical that sprint speed would be relatively stable because running is not contingent on many external variables (assuming the player is actually sprinting). This is in contrast to, say, post-contact hitting or pitching results, which are dependent on what type of contact the batter made, defensive positioning, and defensive skills, among other factors.

The most notable aspect of the two charts is that last year’s team appears to have had more top-end speed. Keon Broxton in center field is notable on both charts, but Hernan Perez at third base and both Villar and Arcia at shortstop are faster or roughly the same as the team’s second-fastest player this year, which is also Perez in the time he has spent in left field. The addition of Travis Shaw has drastically affected the team’s overall speed, as has Villar’s injury. Instead of having a series of speedsters in the lineup, this year’s Brewers team is more sandwiched around league average.

What it has not done, though, is change the team’s overall baserunning performance. In fact, thus far in 2017, the Brewers are a better baserunning team than they were last year, as they currently sit fifth on the BRR leaderboard. Most notably, Arcia and Villar have improved greatly even as they have slowed down, and Travis Shaw has also been a positive despite his lack of foot speed.

Much of the surface appeal of this data is entertainment; the graphics provide a clear visual that allows us to quickly compare players within their position and then across the league. However, it also has some informative value at this stage, both for individual players and for the team.

Villar and Arcia are both slower this year than they were last year, and the rest of the team’s personnel is right about the same. Domingo Santana, Ryan Braun, and Keon Broxton haven’t changed much, and Eric Thames is faster than Chris Carter but not to the extent that he would be a massive upgrade. Overall, though, the team is better at baserunning. What this tells us about Villar and Arcia is that they are capable of being smarter baserunners than they were last year, but they are also capable of running faster than they are this year.

Sprint speed and baserunning aptitude seem like they would be independent skills, both from each other and the rest of the game. Conflating these two together makes more sense than something like BABIP and home run rate would, for example, because BABIP is contingent on quality of contact and defense, while home run rate is partially luck-dependent. As for running, though, the players simply need to run fast and then take extra bases where possible. They are certainly contingent on opportunity, but such is the case for everything measurable in the game. Therefore, expecting that it is at least possible that the Brewers’ double play duo puts together the two skills is eminently reasonable. At the very least, what it tells us is that the two players have figured out how to be better on the bases, even if it meant sacrificing some opportunities to try for the next base with reckless abandon.

On the team level, what it tells us is that the Brewers can squeeze extra wins from good baserunners without chasing speed. Shaw has been a good baserunner this year despite being slow, and, as mentioned above, Villar and Arcia have improved despite slowing down. The Brewers will need to win at the margins if they want to make the playoffs, and they appear to be exploiting baserunning to further that goal.