Brewers fans are undoubtedly, and justifiably, thrilled with Brandon Woodruff’s debut performance thus far in 2017. The rookie righty surged onto the scene last season, after previously making a bit of noise prior to 2015 as a “Prospect on the Rise” as a late-inning relief option. The trouble with fan appreciation of Woodruff is that much of the focus is oriented toward minor league statistics, and less attention is paid to the disparity between scouting rankings.

Related Reading:

Revisiting 2014

Weekend Recap (August 7)

Woodruff: Breaking Through in 2016

Aces Do Not Exist

For example, Woodruff failed to make the Top Fifteen prospects mentioned by Baseball Prospectus for the 2017 Brewers system update (either as a Top 10 option or other prospects of note listing), and that ranking is arguably rightfully so. Woodruff’s fastball, offspeed, or command profile was never going to get him top rotation or elite relief projections (like Josh Hader or Luis Ortiz), and in terms of righty starters, a gang of back-end rotation profiles compete with Woodruff (Cody Ponce, pre-injury Devin Williams, and Marcos Diplan served as this RHP trio entering 2017). Of course, several scouting outlets liked Woodruff quite a bit entering 2017, which fueled some of the expectations that the rookie could build on his 2016 campaign to reach the MLB as a rotation leader.

From Brewers postgame notes, Woodruff is the first starter in franchise history to allow two or fewer earned runs in each of his first 4g.

— Adam McCalvy (@AdamMcCalvy) September 3, 2017

Here we are once again, the stats failing to disappoint: Woodruff has made a franchise milestone with his first four games started, allowing only four runs in his first 23.7 innings. The periphery is barking a bit louder, however, as a 20 K / 9 BB mark defines the results of Woodruff’s current strike zone command, and the 52 percent groundball rate is unassuming. Deserved Run Average (DRA), which assesses a pitcher’s performance according to the run value of their pitching context, pegs Woodruff at 4.73, or 12 runs allowed, triple his actual output. Granted, this DRA is still a fantastic start for a rookie; in the current Miller Park / National League environment, it ranks out as a 100 (perfectly average). It is no insult to suggest that Woodruff is grading out as an average pitcher; but it is indeed worth investigating the elements of this assessment before fan sentiment gets too hungry for Woodruff to serve as a top rotation starter.

Once again, the mantra should continue to be: The Brewers mostly have a gang of very solid middle-to-low rotation pitchers developing in the minors. That’s a good thing, and each 23.7 inning performance to the contrary need not serve as counterfactual to years of scouting assessments. But, this mantra should not be a wet blanket, either; fans should be excited about Woodruff, and they should get to know the righty and his arsenal now that he has several MLB games under his belt.

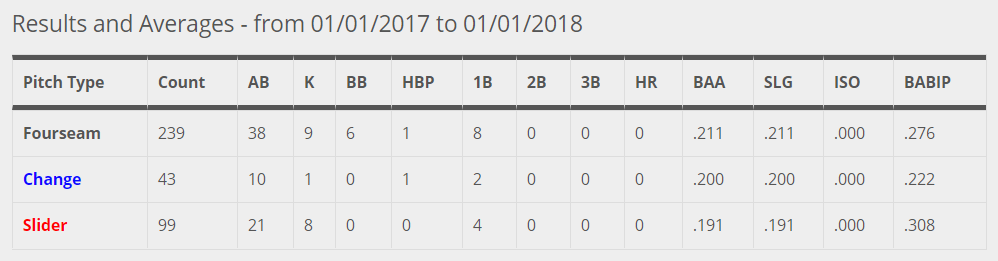

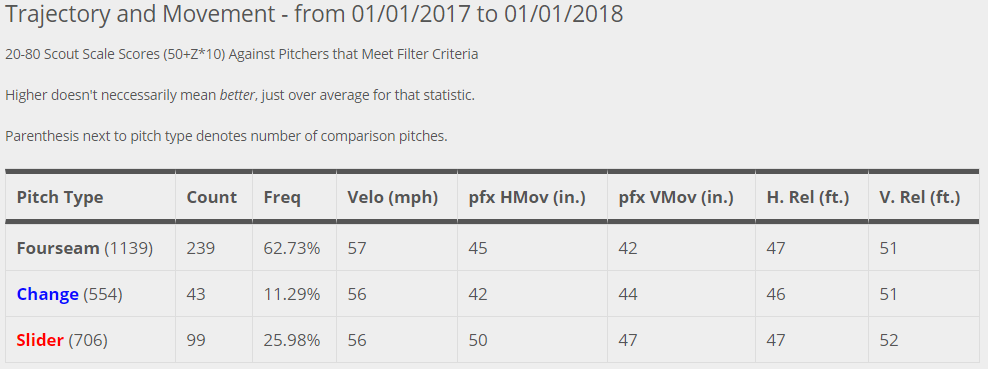

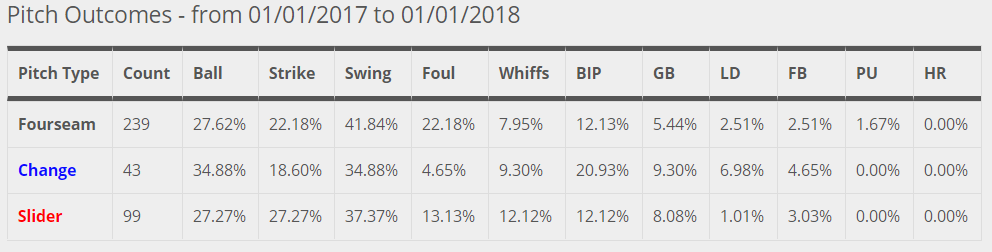

Thus far, Woodruff is working primarily as a fastball / slider pitcher, which aligns with most scouting reports from his advanced minors performances. The fastball is averaging approximately 94 MPH, according to Brooks Baseball, and the sharp slider dives in at 85 MPH, giving the righty quite a velocity differential. From Woodruff’s arsenal to his 6’4″, 215 pound frame, the righty looks like a classic 1970s or 1980s starter pumped up a bit for the current era, ready to work a solid meat-and-potatoes approach built around stuff that is largely flat and tight. The slider is the wipe out pitch thus far, yielding the highest share of strike outs for Woodruff (in terms of strike outs versus number of pitches), and the slider is also yielding the lowest overall batting average (although that’s inflated by the strike outs; the change up has been the best offering for limiting batted balls in play (BABIP) thus far).

So far, so good. This is the profile of a pitcher that has prevented approximately eight runs in only 23.7 innings. The obvious question is not, “What’s up with DRA?” or “Why does DRA ‘hate’ Woodruff?,” but rather, “Does Woodruff’s stuff and approach warrant this level of runs prevention?” For in this case, explaining the stuff might be the better way to construct a picture of one potential future for Woodruff.

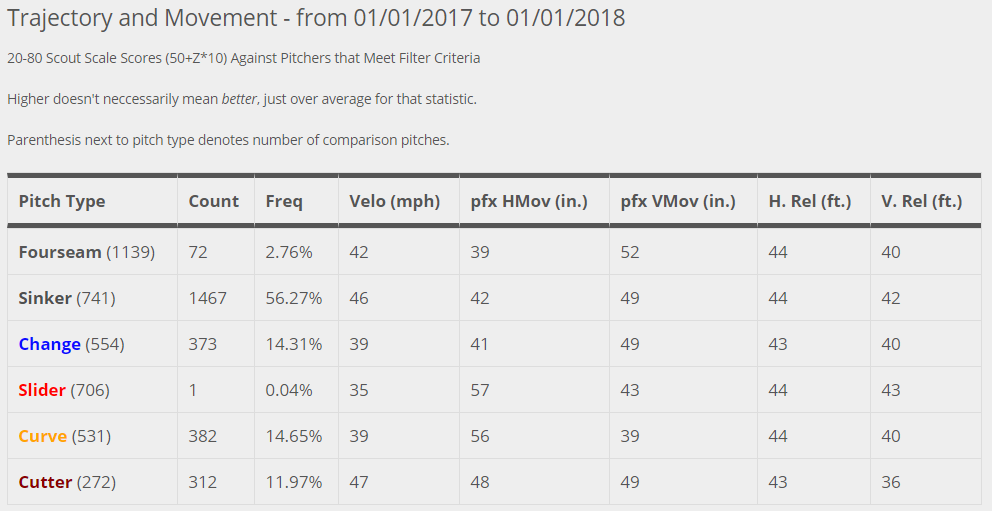

Using the Brooks Baseball “Scout” tool, where pitches are statistically assessed (see the Z Test) and then indexed to the scouting 20-to-80 scale (50 as average), one can judge Woodruff’s stuff against the typical MLB fastball, slider, and change up. While the velocity looks solid across the board, grading better-than-average for the full repertoire, one should note that in terms of break (movement) tracked by PITCHf/x, Woodruff’s stuff does not necessarily dart around the zone. Granted, Woodruff’s stuff is mostly close to average in terms of break or movement, and it should certainly be stated that one need not have better-than-average stuff in order to consistently produce at the MLB level; here’s Woodruff’s low rotation mate Zach Davies, for example:

The Brewers are building quite an unconventional rotation in some respects; a 31-year-old rookie ace in 2016 (Junior Guerra), the diminutive-but-strong Davies as a rotation workhorse, comeback kids Jimmy Nelson and Chase Anderson in 2017, and Fastballer Brent Suter are just a few such examples (as an aside, I did not call Suter a “junkballer” because he throws his fastball 70 percent of the time (!!!), throws his change up least frequently of his major pitches, and his fastball is arguably his best pitch) . This builds on what seems to be a club tradition of seeking overlooked low velocity starters, or seeking a particular release point profile (see Fastballer Mike Fiers and Marco Estrada, both serviceable rotation members, as two such examples). In this sense, Woodruff will feel quite at home if some aspect of his stuff is not phenomenal; indeed, no one will complain if Woodruff’s stuff does not measure up but he mixes and matches to maintain MLB success. A pitcher does not categorically need velocity, movement, deception, command, etc, to succeed, but merely some combination of those traits to get the job done.

The outcomes are what matters; pitching is not necessarily even the sum of all parts, but rather some substantive demonstration of repetition, strategy, and tenacity. In this case, one can see that nothing necessarily leaps off the charts for Woodruff. To place his whiffs in context, the percentage of strikes Woodruff yields per swing lands him solidly in the 65th percentile of all starting pitchers with 200+ fastballs in 2017. Incidentally, Woodruff also ranks near the 65th percentile with his slider, in terms of whiffs per swing (for starting pitchers with 50+ sliders in 2017). These rankings are quite good; not elite, but good, which reflects Woodruff’s overall stuff profile as well.

To this point, one might surmise that Woodruff is succeeding in part due to his better-than-average velocity profile, which may gloss over some of his subpar break or movement profiles on his pitches. Assessing zone profiles is also another way to work alongside Woodruff’s approaches to supplement discussion of stuff.

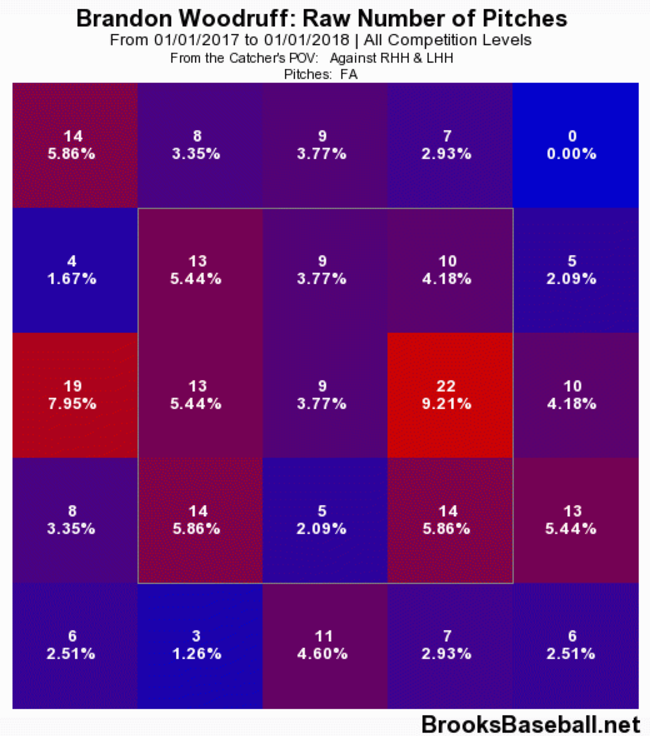

In terms of fastball, overall Woodruff has shown the ability to work on both armside and gloveside areas of the zone. Moreover, the rookie shows a tendency to cluster pitches in areas of the zone that might not hurt him. He stays away from the middle of the zone while throwing nearly 25 percent of his fastballs to the low-and-middle glove side quadrants on the corner of the strike zone; another 22.6 percent of his fastballs work armside in the low-to-middle quadrants on the corner of the strike zone. What is fascinating about this approach is that Woodruff is not missing low; hardly 9 percent of his total fastballs miss below the strike zone in these areas, despite his preference for working in these clustered areas.

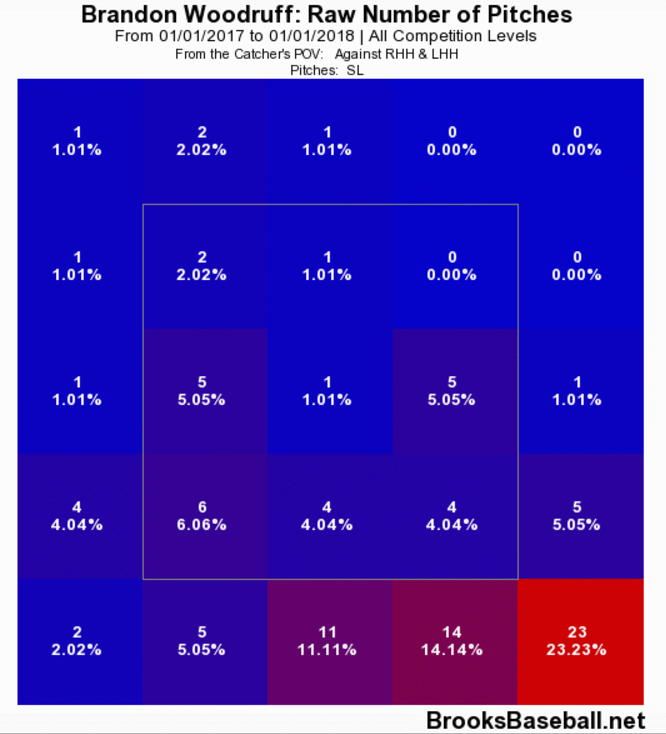

This fastball diversity is necessary because the slider….well…

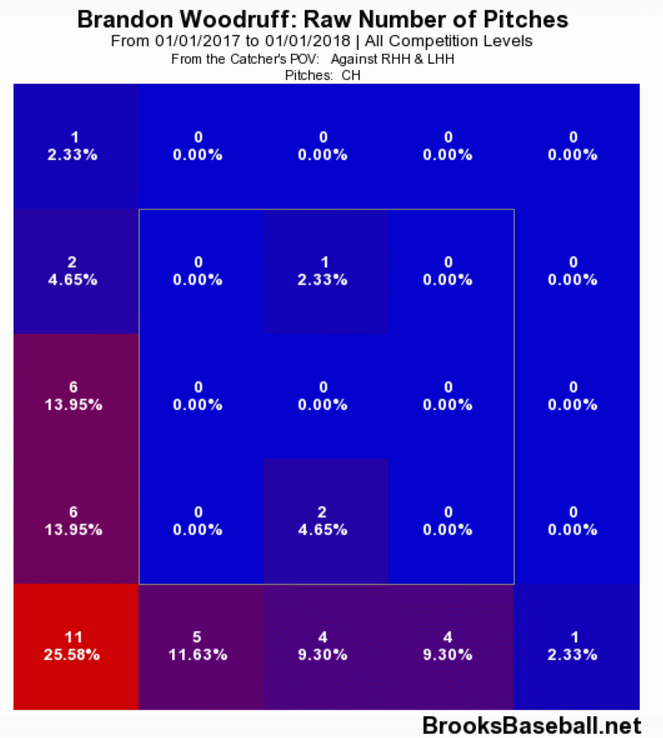

The slider hardly hits the strike zone, and it lands almost exclusively gloveside. This is consistent with the PITCHf/x movement noted by Brooks Baseball, as the slider breaks approximately 5.5 inches gloveside while dropping approximately 7.0 inches measured against the primary fastball. That Woodruff is throwing his slider basically according to its mechanical break is offset by the change up, which also reflects the mechanics of the pitch:

Measured against the fastball, the change up “runs” armside by nearly 4.0 inches while dropping approximately 4.0 inches, which is certainly reflected in this zone approach.

One can gather that these strike zone charts show the clear road for advancement by Woodruff. As batters are prepped on the righty, it will be clear that going off-speed, batters can expect both the slider and the change to work within very clear hitting zones. Granted, it is much more difficult for batters to “guess” on these pitches if the righty can work the fastball to either side of the plate within several areas on the edge of the strike zone. But at a certain point, the righty will need to show that he can work somewhat within the zone with both his slider and change up, and perhaps work either pitch to a different side of the plate. Yet, even if Woodruff cannot accomplish this, it should be clear why having three pitches is typically a scouting necessity to succeed as a starter: even without diversifying the location of his slider and change, and indeed simply throwing both pitches according to their mechanical purpose, Woodruff can give batters a couple of wrinkles to consider while he’s pounding the zone to both sides with his fastball.

From this profile of Woodruff’s stuff, one can now progress to the favorite fan question, “Why does DRA ‘hate’ ______________?” (usually, “Insert my favorite pitcher”). Baseball Prospectus publishes DRA Run Values to demonstrate the modeling components that construct the statistic. These Run Values include NIP (“Not In Play”) Runs, Hit Runs, and Out Runs, which respectively assess each pitcher’s runs saved or runs given up on balls that are not in play, balls that are hits, and outs generated on balls in play (the link provided features a glossary for each statistic).

In Woodruff’s case, the rookie is basically an average pitcher in terms of expected run values. Woodruff is dinged a bit on “Out Runs,” but saved runs in equal parts in terms of “Hit Runs.” In terms of “NIP Runs,” that 20 K / 9 BB ratio leads Woodruff to a neutral-to-very slightly below average profile when the ball is not in play. What this basically means is that Woodruff is not categorically getting hit hard, but also is not categorically preventing runs by inducing outs with the profile of his batted balls in play. Given that Woodruff’s stuff features solid velocity but below average movement, one might expect the righty to work stretches in which he is able to enhance weak contact performances, and also stretches in which he will fail to fool bats.

This is a tricky line to walk in terms of discerning value, but the overall profile should suggest that Woodruff can use his stuff to limit the damage by working his fastball across the zone. However, the righty will arguably face further difficulty if he is unable to diversify both his slider and change usage across the zone. Yet, even where Woodruff has some potential trouble in these areas, the righty’s overall approach is relatively neutral in terms of his alignment of preventing hard contact and using his defense.

There is enough in Woodruff’s profile that should lead fans to wonder when and how the rookie will prevent runs for the Brewers rotation, but there are also enough question marks with the profile that one should not yet crown Woodruff a likely ace. The latter assessment, that Woodruff is destined to acehood, is unfair to a righty that has never had that scouting determination. But as Woodruff has shown thus far, once a pitcher is working between the lines, there can be so much more to the outcome than the mere sum of the parts. This is both a conundrum of acehood, and a recognition of the thrilling potential of graduating real live middle rotation starters to the MLB: without aces in Milwaukee, fans will find the excitement of building a rotation where many arms are quite capable to take their turn every five days.

Photo Credit: Benny Sieu, USAToday Sports Images